The Connaught Fund was founded in 1972 when U of T sold the Connaught Medical Research Laboratories for $29 million. The lab had been established in 1914 to produce diphtheria antitoxin. After the 1921 discovery of insulin by U of T researchers Frederick Banting and Charles Best, the lab expanded and began producing insulin as well as other vaccine[s] and antitoxins.

These three lines are all the University of Toronto’s Connaught Fund website currently says about the origin of the Fund and the history of Connaught Medical Research Laboratories. They are given as “Point Three” of “Five Key Points” necessary to “Understanding Connaught.” Point Four emphasizes, “Connaught is the largest internal university research funding program in Canada. Since 1972, it has awarded more than $160 million to U of T scholars. The original $29 million was endowed. Today, Connaught is worth over $120 million.” And Point Two notes, “Some funds are specifically designed for young researchers to get their research careers started. Other funds focus on interdisciplinary work and innovation — with a strong emphasis on meeting challenges facing global society.”

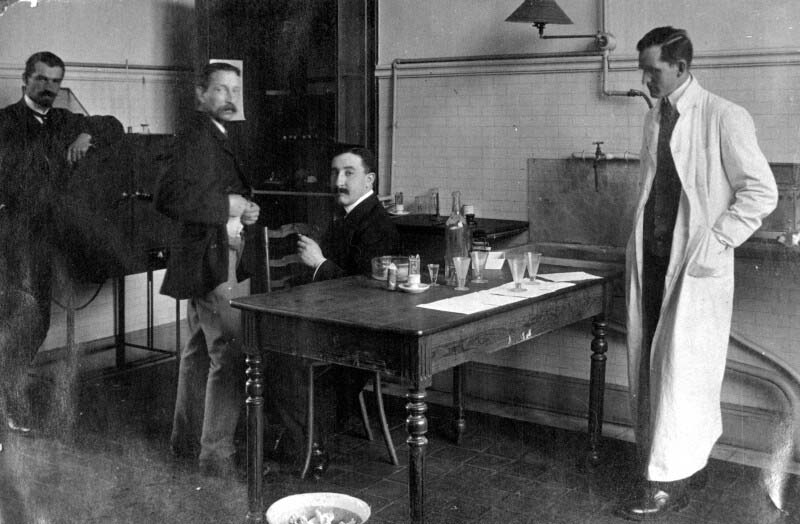

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

However, to really understand the unique story, mission and remarkable success of the Connaught Fund, one needs to more fully understand the similarly unique story, mission and remarkable success of Connaught Medical Research Laboratories while it was a singular part of the University of Toronto. After reading those three lines, one is certainly left with a number of questions: Why did U of T sell Connaught Laboratories in 1972? What is diphtheria antitoxin and how did the need for a Canadian supply drive the establishment of the Laboratories in 1914? How did the Antitoxin Laboratory grow to become Connaught Laboratories? What was Connaught’s role in the insulin story? What was the Laboratories’ role in the development and production of vaccines? Who started Connaught Laboratories, and who was Connaught anyway? And how does the Fund’s emphasis on supporting young researchers, interdisciplinary work and innovation, directed especially towards global challenges, relate to the original mission, evolution and unique academic and pragmatic public health culture of Connaught Laboratories?

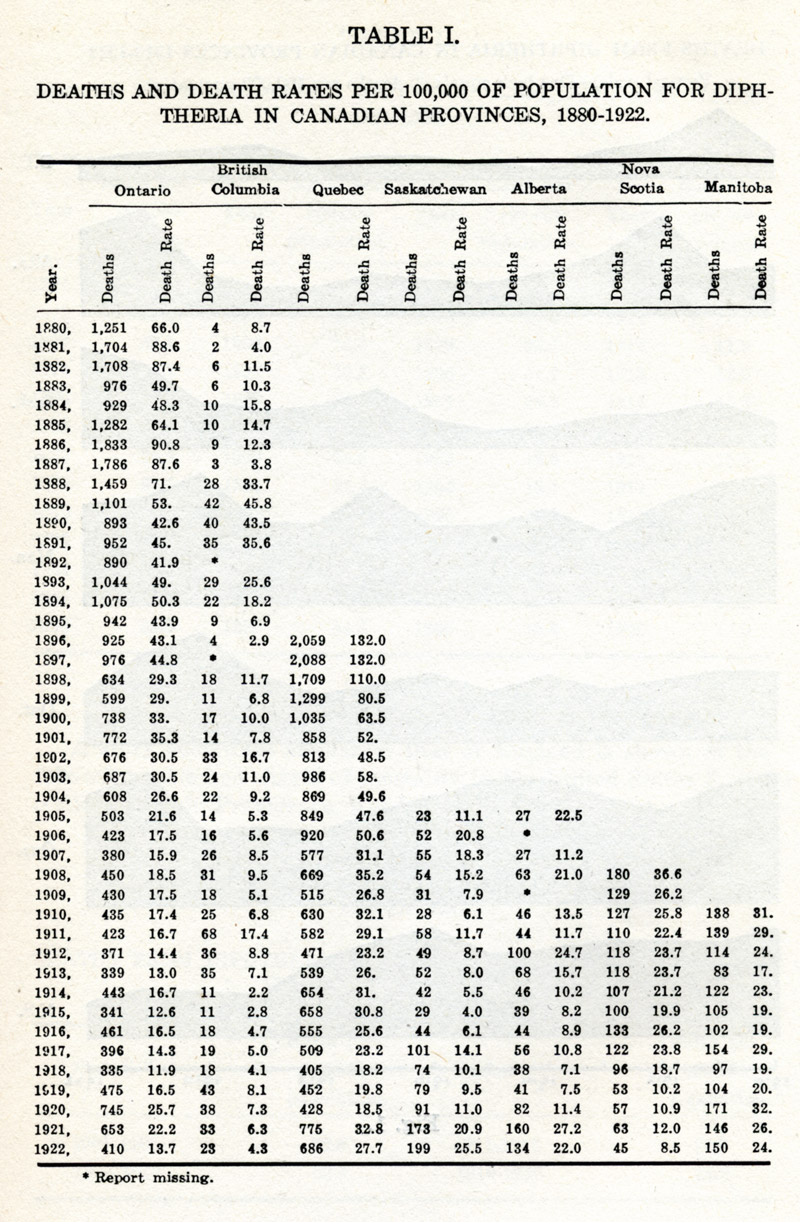

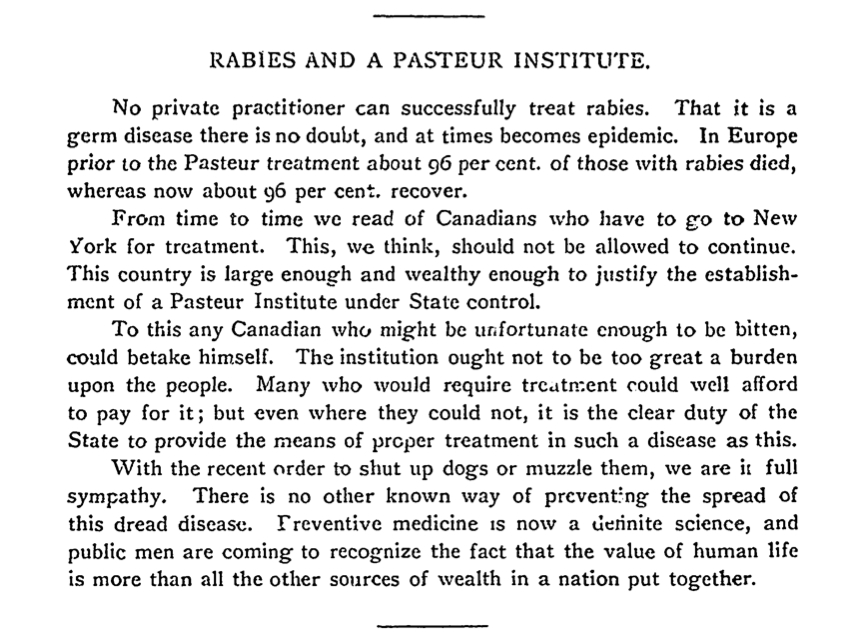

[Public Health Journal (Sept. 1923), p. 389.]

This is the first in a series of feature articles for the Connaught Fund website; the articles are designed to answer these and other questions about the history of the Fund and, in particular, the history of Connaught Laboratories when it was a self-supporting part of the University of Toronto. Since 1972, Connaught Laboratories has undergone several significant transformations and today, as Sanofi Pasteur Canada, it remains a vital part of the Canadian and global vaccine and biotechnology industry. Sanofi Pasteur Canada operates from its Connaught Campus, founded over a century ago and located near Steeles Avenue West and Dufferin Street. Sanofi Pasteur Canada has supported a variety of initiatives to preserve, apply and promote its rich history, particularly through employing my professional historical research, writing, archival, consulting and creative services since 1995, following the completion of my Ph.D. in Canadian History from the University of Toronto. My dissertation was on the history of polio in Canada and involved research in the Connaught Laboratories Archives. My thesis supervisor was Professor Michael Bliss, author of The Discovery of Insulin. Most prominent among the historical projects I have curated for Sanofi Pasteur Canada have been its Heritage Room and its “Legacy Project” website (http://thelegacyproject.ca). The Connaught Campus Archive is an especially rich resource of documents and images, most of which date from Connaught’s University of Toronto era. This series of articles will draw from this collection, as well as from the University of Toronto Archives and the files of the Connaught Fund.

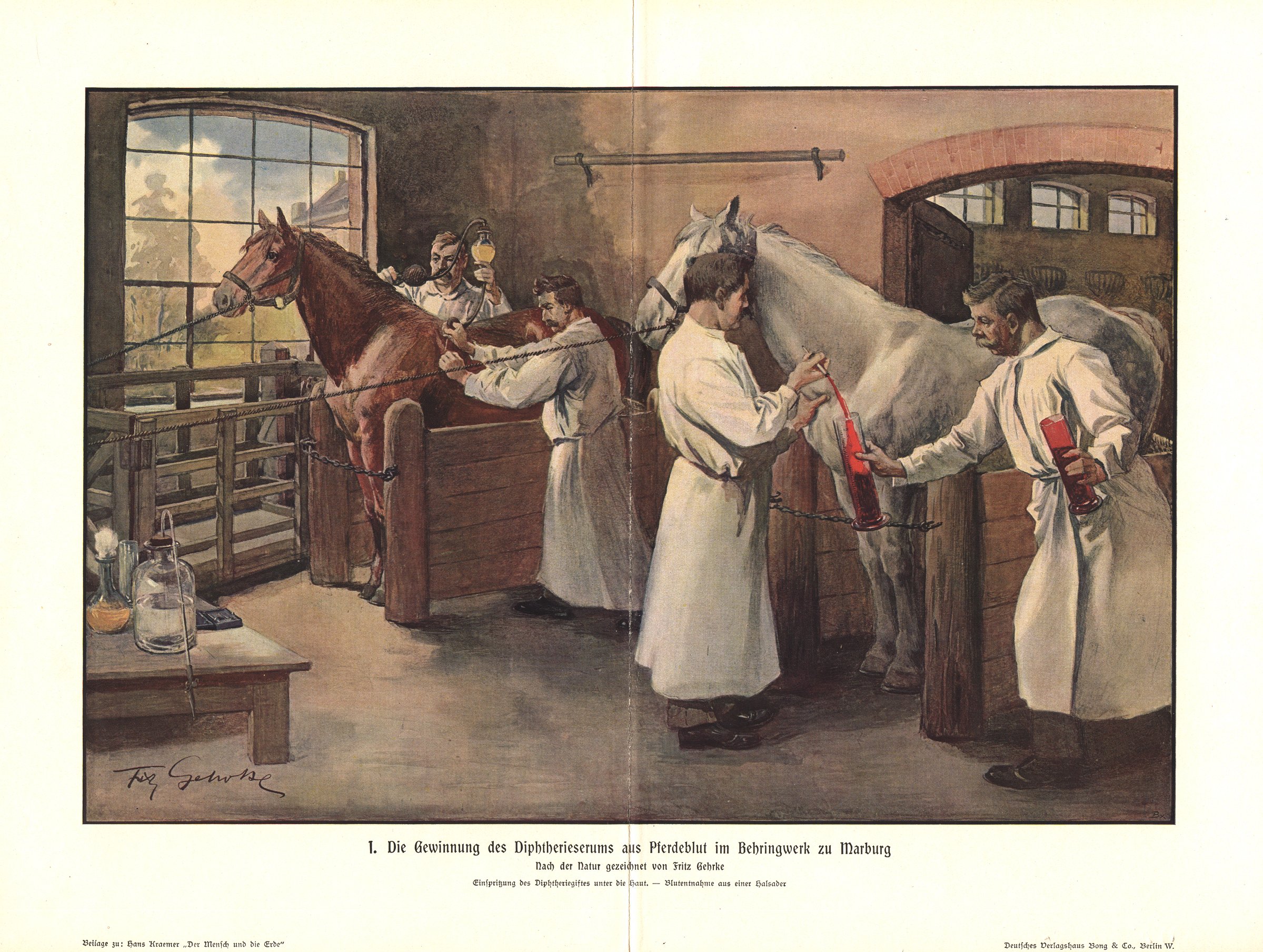

[Image from National Library of Medicine]

Connaught Laboratories originated within the uniquely Canadian public health context of the 1890s to 1910s, a period defined by increasingly pro-active local and provincial (but quite limited federal) public health efforts to control infectious diseases, especially diphtheria, the incidence of which was increasing due to rapid urbanization. Indeed, diphtheria was the leading cause of death among Canadian children under 14 until the mid-1920s. In Ontario alone, 36,000 children died from diphtheria between 1880 and 1929. Known as “The Strangler,” diphtheria is a bacterial infection normally transmitted through close contact with an infected individual, usually via airborne routes. Corynebacterium diphtheria produces a toxin that spreads in the body, the infection producing a thick, sticky film in the throat that makes breathing increasingly difficult. In the 1880s, the diphtheria bacterium was first identified and diphtheria toxin cultured. In the following decade, a German researcher developed diphtheria antitoxin by injecting horses with a series of small doses of diphtheria toxin. The size of the doses was progressively increased, harmlessly stimulating immunity. Some blood was then drawn from the horse, and the antitoxin was refined from the white blood cells and then used to treat people infected with diphtheria. When given early enough in the course of the disease, and in large enough doses, the antitoxin could save lives. Canadian public health efforts to combat diphtheria were largely dependent upon the import of the diphtheria antitoxin from U.S. commercial pharmaceutical firms. Of particular concern, the antitoxin’s price, especially after the levying of an import tax, was often beyond the means of middle class families threatened by this deadly disease.

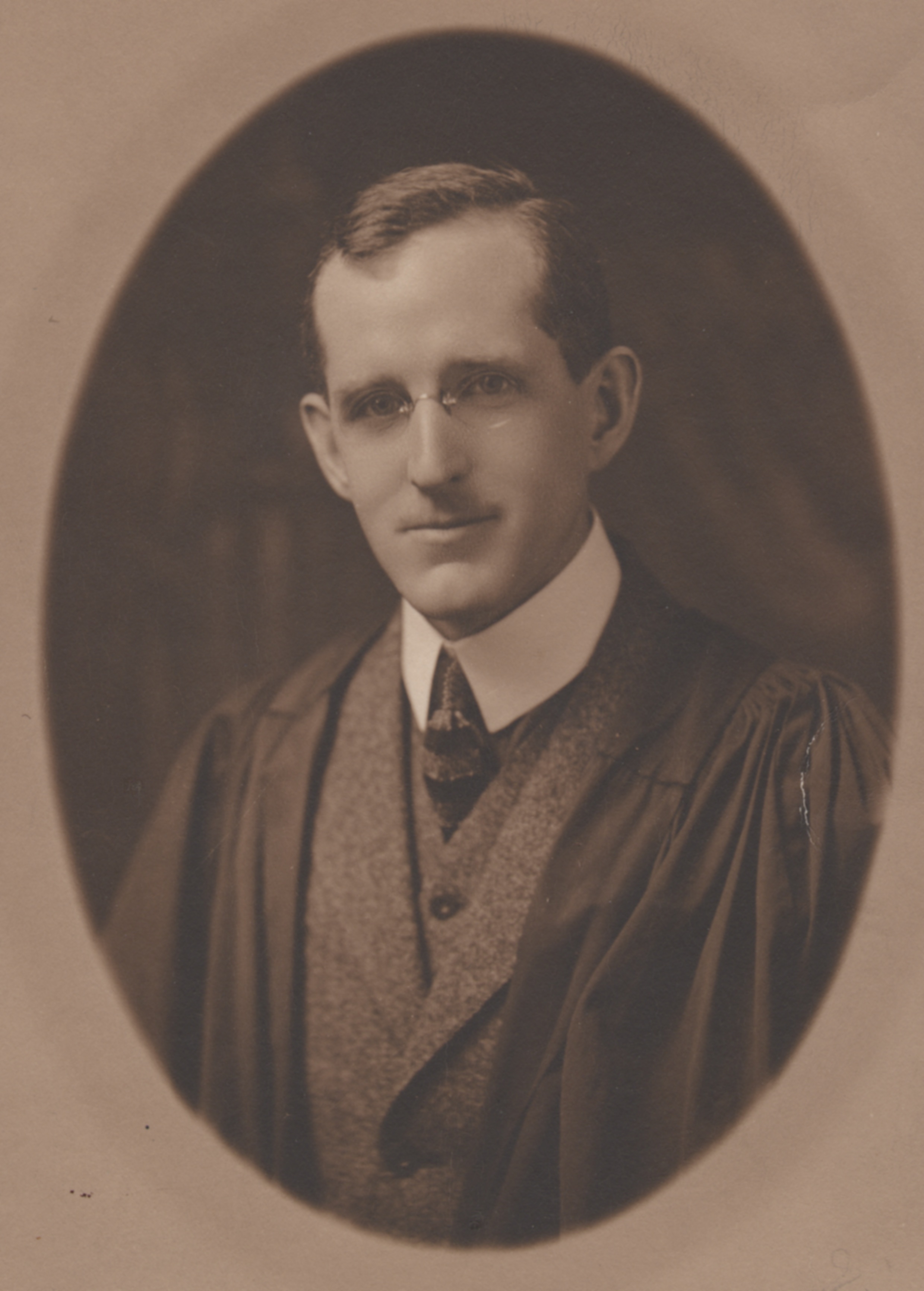

[Image courtesy of James FitzGerald]

The origin of Connaught Laboratories primarily stemmed from the unique public health vision and fearless determination of Dr. John Gerald FitzGerald (1882–1940). FitzGerald’s energetic life, his tragic death and its impact on the next two generations of his family are the main focus of the award-winning book by his grandson, James FitzGerald, entitled What Disturbs Our Blood: A Son’s Quest to Redeem the Past, published in 2010. You can learn more about the book via James’s website (http://www.jamesfitzgerald.info/Madness.html).

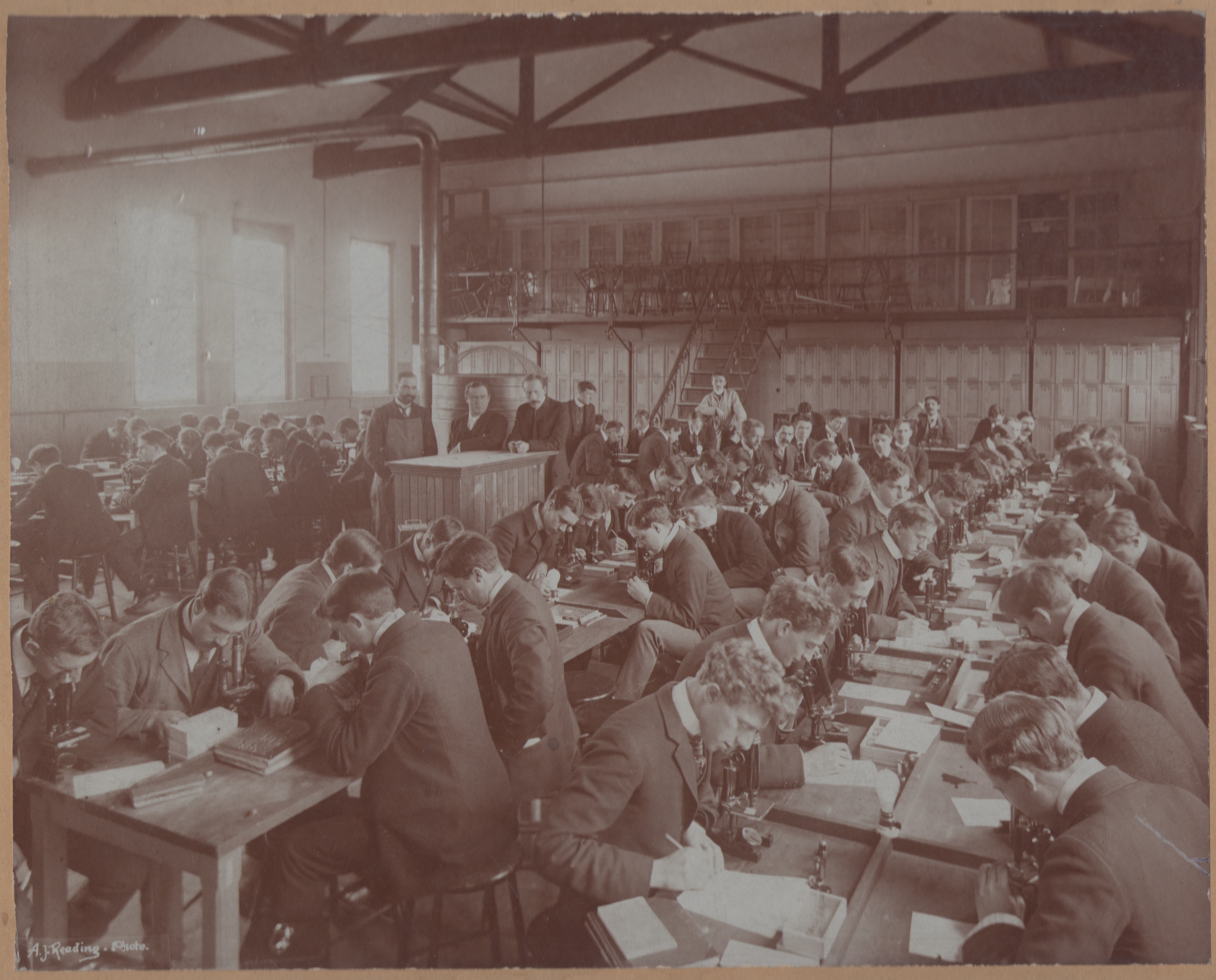

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

Born in the village of Drayton, Ontario, the eldest son of a pharmacist, the tall, slim, red-headed “Gerry” FitzGerald became one of the youngest graduates of the University of Toronto Medical School in 1903. After a stint as a ship’s surgeon, then internships in neurology and psychiatry in the U.S, in 1906, FitzGerald was appointed the first pathologist and clinical director of the Toronto Asylum for the Insane. Swept up in the revolutionary bacteriological discoveries of the time, he was especially interested in the prevention of mental diseases. However, FitzGerald soon realized that progress would be painfully slow and, in 1907, switched his focus to the more promising advances being made in the field of bacteriology, especially when applied to the treatment and prevention of infectious diseases. The use of diphtheria antitoxin was of particular interest.

[Image courtesy of James FitzGerald]

By the summer of 1910, following additional bacteriological studies at U of T and Harvard, FitzGerald coupled his honeymoon with further study at the Pasteur Institute in Brussels, followed over the next two years by a professorship in bacteriology at the University of California and yet more studies in Germany, at the Lister Institute in London and at the New York City Department of Health. During this period of extensive international travel and network building, FitzGerald soaked up unique knowledge and experience in bacteriology and public health, learning how to make antitoxins as well as the Pasteur Rabies Treatment, originally developed by Luis Pasteur in 1885 to counter the otherwise fatal bites of rabid animals. FitzGerald also observed novel approaches to public health education and research, as well as the production of biological products. He was eager to apply these approaches when he returned to Toronto in the spring of 1913 and took up his new role as part-time Associate Professor of Hygiene at the University of Toronto.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

Armed with his unique knowledge, FitzGerald was asked to prepare Canada’s first rabies vaccine treatment supply for the Ontario Provincial Laboratory. A rabies outbreak in early 1910 among dogs in southwestern Ontario led to the death of a young boy and to subsequent calls for a “Pasteur Institute” in Toronto. With no local supply available, for people bitten by rabid animals treatment was available only to those who could afford to travel to the “New York Bacteriological and Pasteur Institute” to receive the life-saving rabies vaccine treatment. FitzGerald worked with William “Billy” Fenton to prepare the rabies vaccine, Fenton offering himself as human guinea pig to test it. Fortunately, the vaccine passed the test, and rabies remained quite rare in Canada. FitzGerald and Fenton spent more time discussing diphtheria toxin, especially the absence of an inexpensive supply in Canada. FitzGerald knew how to make the antitoxin, and he had a network of experts available for advice, particularly at the New York City Health Department Laboratory, which prepared antitoxins and vaccines for the city as a free public service. He also had a commitment from Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer that the Provincial Board of Health would buy the antitoxin at cost and ultimately distribute it for free. On his own initiative, FitzGerald thus decided to make diphtheria antitoxin; he just needed some horses, a place to accommodate them, and a small lab to process the antitoxin.

[news item from Canada Lancet, March 1910, page 484.]

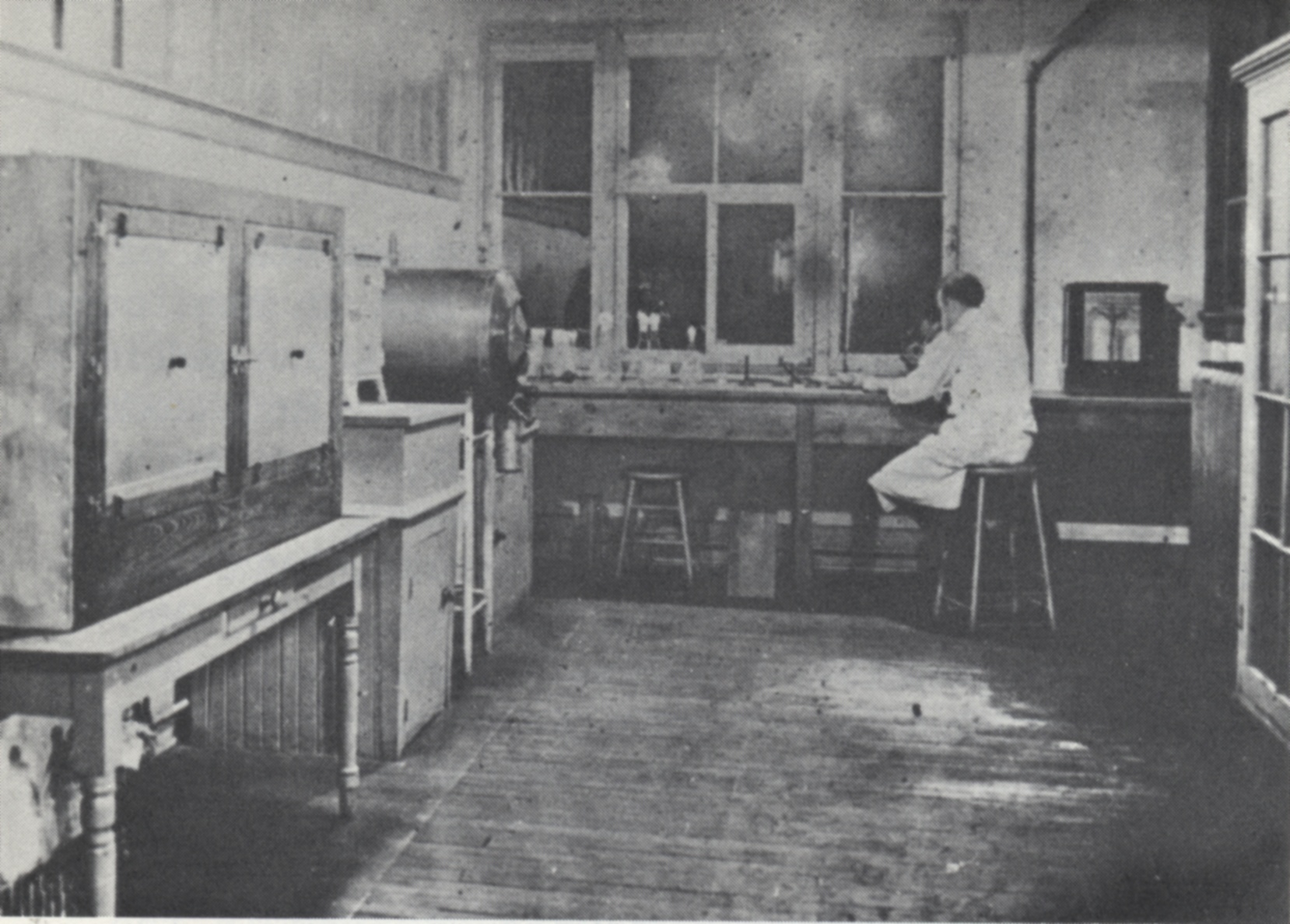

Fenton offered his backyard at 145 Barton Avenue to build a stable with a small lab, and FitzGerald’s wife offered her dowry and some of an inheritance from her father to pay for the initiative. In December 1913, the five horses needed to prepare the antitoxin were acquired for $5 each; they were otherwise headed to the glue factory. The “aged” horses passed the required tests and were named Crestfallen, J.H.C., Fireman, Goliath, and Surprise before they were given their first injections of diphtheria toxin. Over the next 8 weeks the series of increasingly large doses of toxin continued, with little discomfort to the horses, soon after which the blood was tested for antitoxin levels. When the levels were sufficient, some blood was drawn into sterile containers and the white blood cells processed into diphtheria antitoxin. Encouraged by the work in the stable and the commitment from Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer to purchase antitoxin, FitzGerald strongly felt that the University of Toronto should establish something like a “Pasteur Institute.” Thus, in early 1914 he presented a compelling plan to the Board of Governors. They were impressed by FitzGerald’s efforts and bold vision, which included dedicating any proceeds earned from the sales of biological health products to research into new and improved products and to the support of public health education. On May 1, 1914, the University of Toronto formally established the Antitoxin Laboratory in the Department of Hygiene. To get started, the Department’s Museum of Hygiene in the Medical Building basement — a collection of sanitation and plumbing exhibits designed to illustrate the pollution of wells and the transmission of communicable diseases — was sacrificed to provide space for the new Lab.

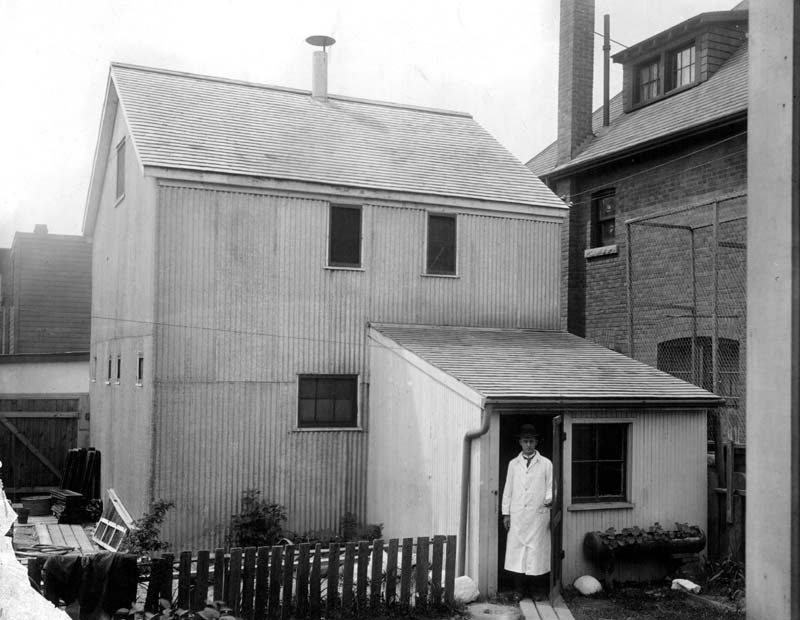

William “Billy” Fenton at the door of the Barton Avenue Stable at 145 Barton Ave., Toronto, in 1914.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Barton Avenue Stable Museum, Sanofi Pasteur Canada]

The Antitoxin Laboratory was to be self-supporting and received no funds from the University. Indeed, Sir Edmond Osler, brother of the famous Dr. William Osler and a U of T Governor, donated $500 of his own money to convert the Museum of Hygiene into three rooms: a general laboratory, a room for washing and sterilizing glassware, and a small bacteriological lab. Space in the sub-basement would be utilized for processing blood plasma into antitoxin and for the packaging and storage of products. Not long after the new Antitoxin Laboratory began preparing diphtheria antitoxin, as well the Pasteur Rabies Treatment, the start of the First World War threatened to derail the Lab’s fledgling work. However, the war, and, in particular, the threat of tetanus among wounded soldiers, would fuel the next chapter in the story of Connaught Laboratories, as will be described in the next article in this series.

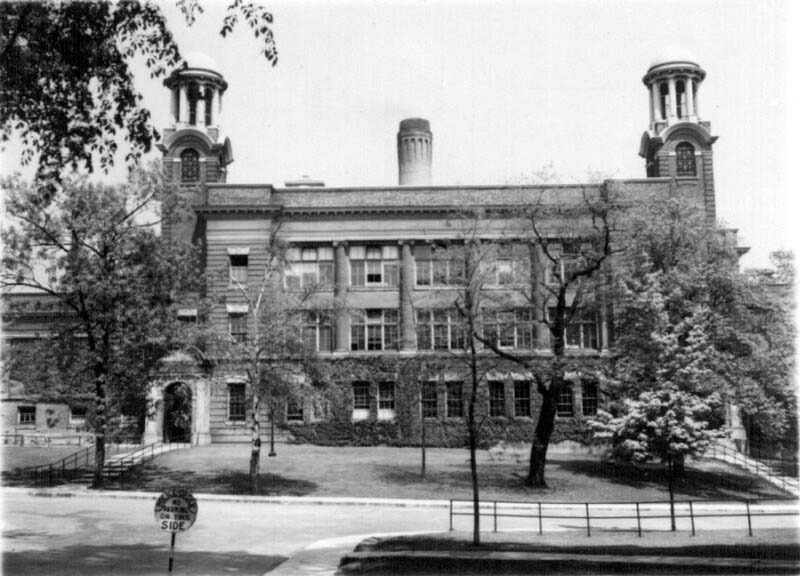

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[University of Toronto Press, 1968, p. 15]

Useful Resources:

Bator, Paul with Andrew J. Rhodes: Within Reach of Everyone: A History of the University of Toronto School of Hygiene and the Connaught Laboratories, Volume 1, 1927-1955 (Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association, 1990) Defries, Robert D.: The First Forty Years, 1914-1955: Connaught Medical Research Laboratories, University of Toronto (University of Toronto Press, 1968) FitzGerald, James: What Disturbs Our Blood: A Son’s Quest to Redeem the Past (Toronto: Random House, 2010); details at: http://www.jamesfitzgerald.info Rutty, Christopher J.: “Personality, Politics and Canadian Public Health: The Origins of Connaught Medical Research Laboratories, University of Toronto, 1888-1917,” in E.A. Heaman, Alison Li and Shelly McKellar (eds.) Figuring the Social: Essays in Honour of Michael Bliss (University of Toronto Press, 2008), p. 273-303; available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/Rutty-ConnughtOrigin-BlissEssays.pdf Rutty, Christopher J. (with Sue Sullivan): This is Public Health: A Canadian History (online ebook, Canadian Public Health Association, 2010): https://www.cpha.ca/history-e-book Rutty, Christopher J. (curator): “Vaccines & Immunization: Epidemics, Prevention and Canadian Innovation: The Online Exhibit,” Museum of Health Care, Kingston, ON (launched November 2014): http://www.museumofhealthcare.ca/explore/exhibits/vaccinations/ Rutty, Christopher J. (curator): “Within Reach of Everyone: The Birth, Maturity & Renewal of Public Health at the University of Toronto,” Dalla Lana School of Public Health website feature (launched 2015): http://www.dlsph.utoronto.ca/history/ Rutty, Christopher J. (curator): Sanofi Pasteur Canada, “The Legacy Project” (launched January 2016): http://thelegacyproject.ca