As emphasized in the first article in this series, the Connaught Fund website originally included three lines about the history of Connaught Medical Research Laboratories; these lines jump from mentioning the Labs’ origins in 1914 to their expansion following the discovery of insulin in 1921. However, a great deal happened at Connaught Labs during the period in between, much of it driven by the major contributions that the Labs made to domestic and military public health during the Great War.

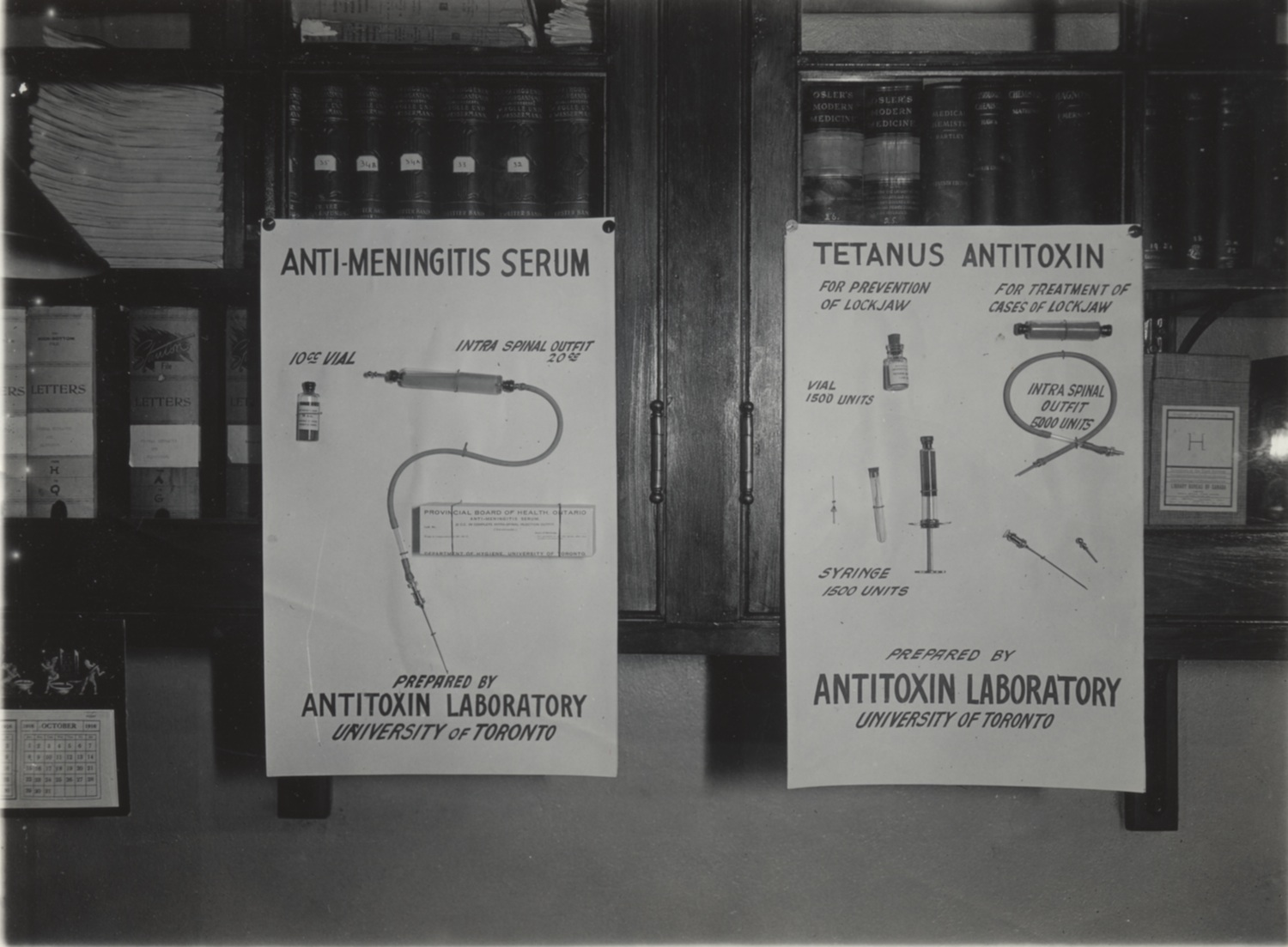

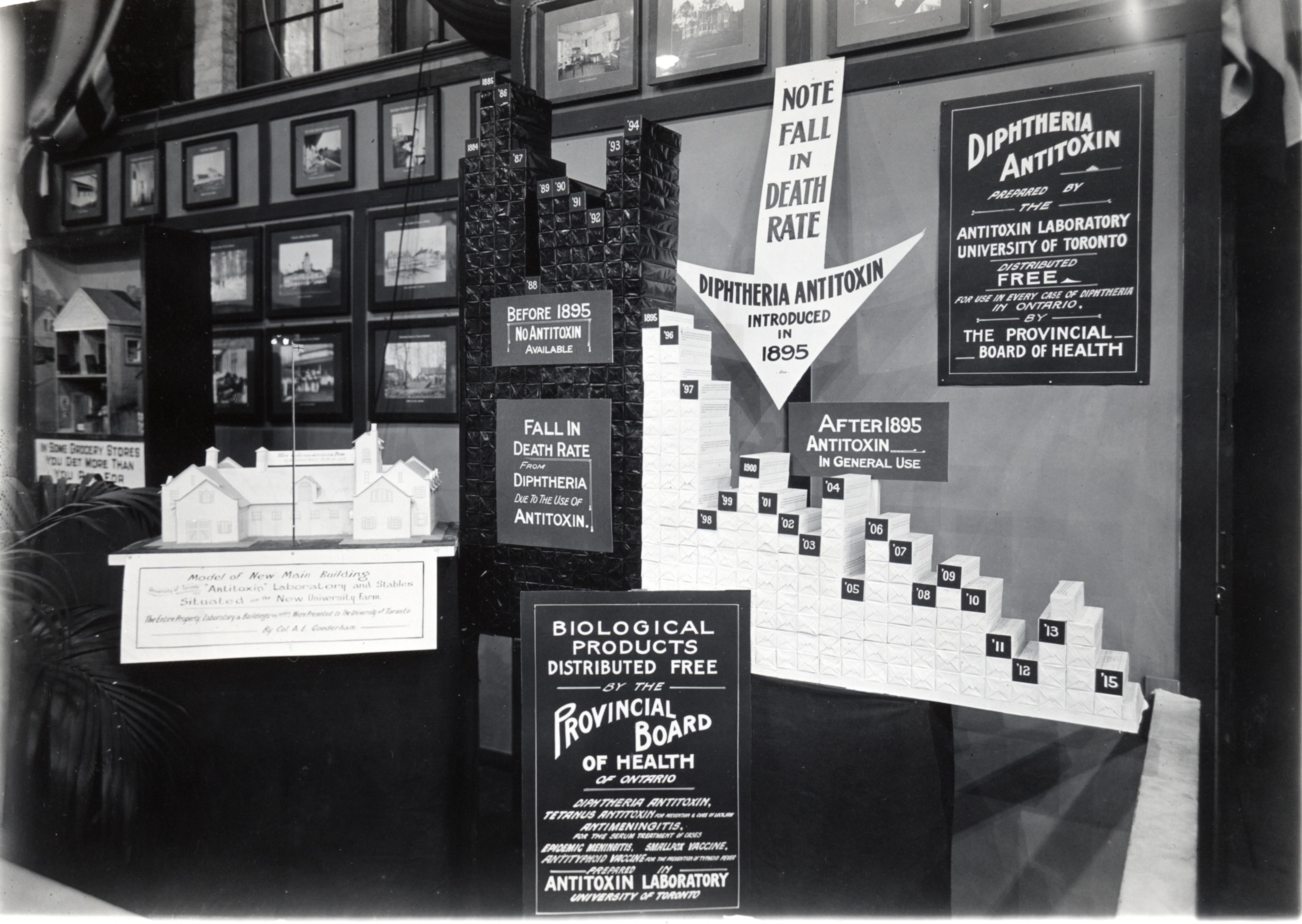

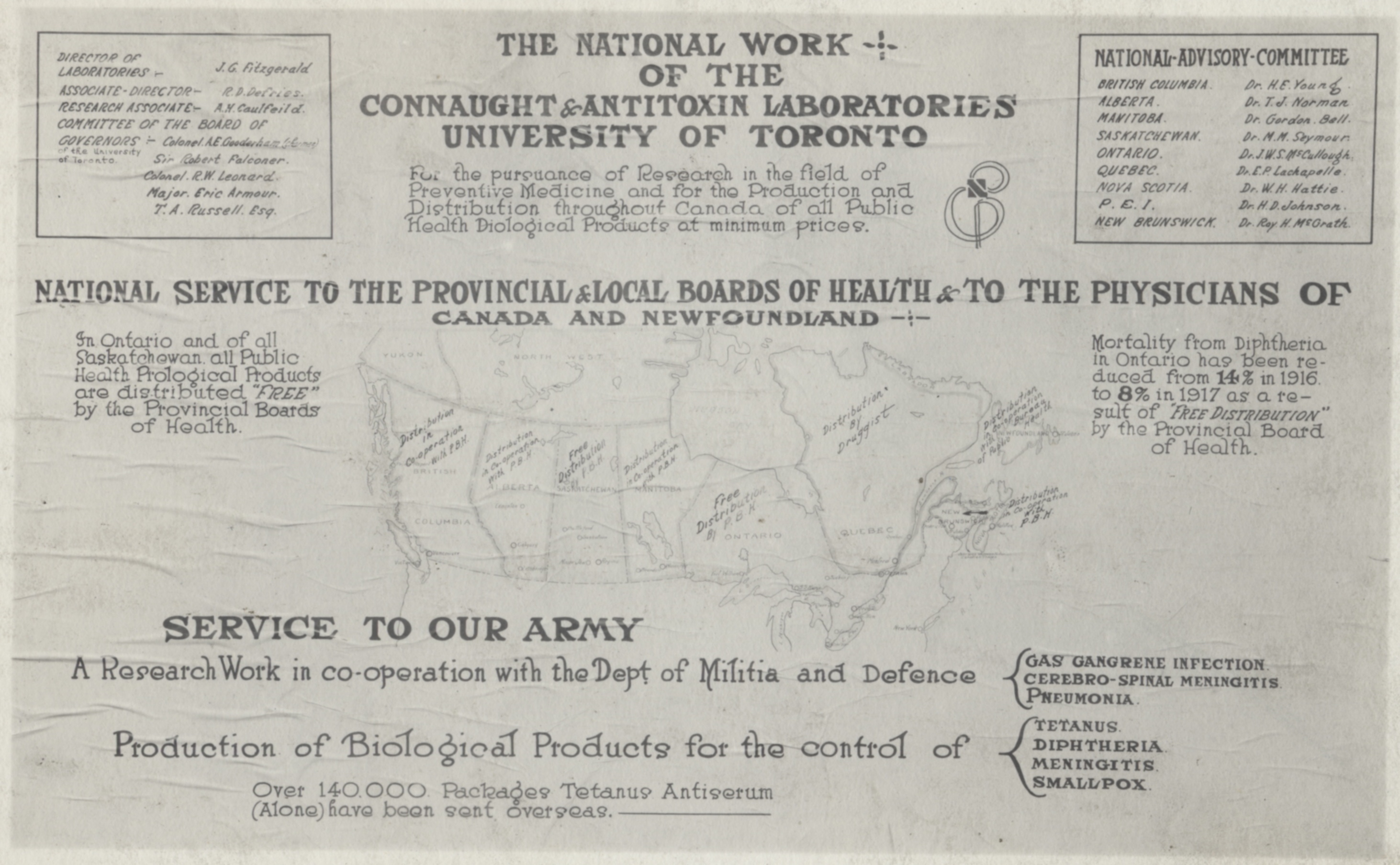

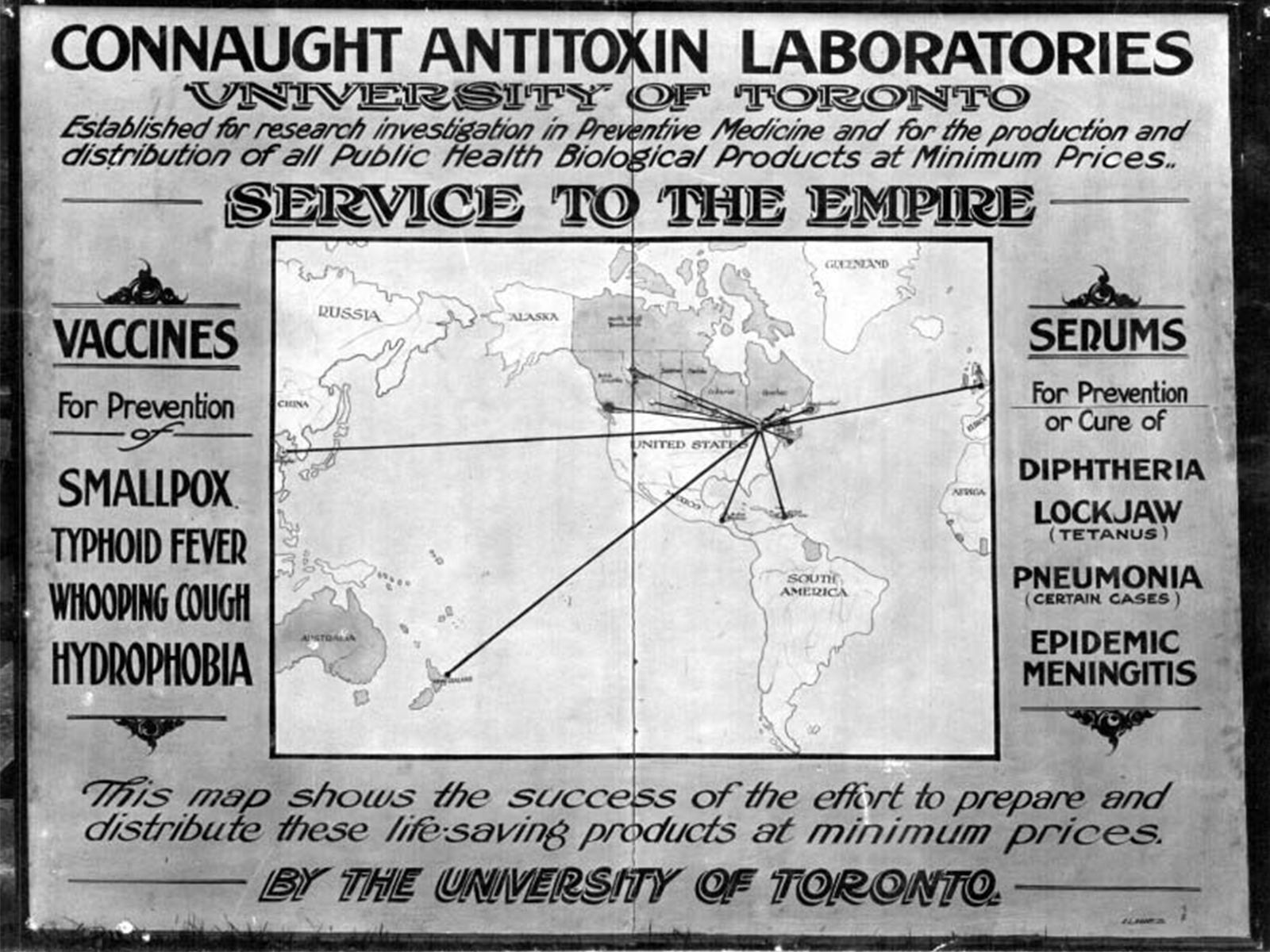

During the summer of 1914, Dr. John G. FitzGerald focused on expanding the Antitoxin Laboratory’s modest facilities in the Medical Building basement and on increasing its output and range of products. In addition to diphtheria antitoxin and Pasteur Rabies Treatment, the Antitoxin Lab began preparing typhoid vaccine, anti-meningitis serum and tetanus antitoxin to meet demands from outside of Ontario. FitzGerald also worked on developing a capacity for research and enlarged facilities for teaching. Reflecting this progress and his optimism, he concluded his first Annual Report to the University of Toronto Governors for the period ending June 30, 1914,

The value of the laboratory is thus greatly enhanced, since the Public Service aspect is made to go hand in hand with teaching and research, a combination possible only when the work is being done in connection with the University. It is the hope of those responsible for the Laboratory that it may in this way be possible to gradually develop in Canada, laboratories analogous in scope to those of the Lister Institute in London and the Pasteur Institute in Paris, Brussels and elsewhere.[i]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

However, after a productive spring and summer, Canada’s sudden entry into World War I on August 4, 1914, threatened to end FitzGerald's ambitious plans prematurely—although the conflict soon provided an opportunity for the fledgling Lab. In November 1914, surprised at the unexpected impact of wound infections, the British Expeditionary Force ordered all wounded soldiers be given prophylactic doses of tetanus antitoxin, an order also given by the other armies on both sides of the conflict. A severe global shortage of tetanus antitoxin was soon at hand, despite the efforts of serum labs in the U.K., France, Germany and the United States.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

Tetanus is an insidious bacterial disease that can cause prolonged and deadly contraction of muscle fibres, with “lockjaw” among its most dangerous effects. Clostridium tetani is harboured in many animals, and the disease develops when spores from the bacterium enter the anaerobic conditions found in dead or damaged cells, or deep puncture wounds. When the spores germinate, tetanus toxin is released and spreads in the nervous system. Clostridium tetani was confirmed as the cause of tetanus in 1884 and tetanus toxin first isolated in 1890. Similar to diphtheria antitoxin, small doses of tetanus toxin stimulate an immune response in horses. Some blood is then collected and the white blood cells containing antibodies is processed into antitoxin. Demand for tetanus antitoxin had remained quite limited until the outbreak of the war, but trench warfare provided ideal conditions for wounded soldiers to be exposed to the tetanus bacterium. At the end of January 1915, Dr. Robert D. Defries, who had just joined the Antitoxin Lab, described the tetanus antitoxin situation to the University’s Board of Governors: "not a fraction of the necessary amount was available," since the entire output was spoken for in advance by the Allied Powers.[ii] Defries had received a M.D. from the University of Toronto in 1913, followed by a Diploma in Public Health in 1914. The DPH was initially offered in 1904, but without a formal course. A DPH course was first offered in 1912 and Defries was the first to complete it, while also serving as FitzGerald’s lab demonstrator. Defries had considered becoming a medical missionary, but was persuaded by FitzGerald to focus on the more pressing mission of public health. Defries outlined a plan whereby, over the subsequent 5–6 months, the Lab could prepare enough of the tetanus antitoxin for every Canadian soldier for $0.65 a dose, compared to $1.25 per dose, which was the lowest price at which the Canadian Red Cross could purchase the serum from the New York City Health Department Laboratory. The plan also included the proviso that expanded stables and laboratories were needed as quickly as possible.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

The Board of Governors quickly approved Defries’ plan, with U of T President Robert Falconer telling Prime Minister Robert Borden that it was a "patriotic duty that we in Canada should manufacture tetanus antitoxin for our own expeditionary forces."[iii] The Board, however, was unable to provide the $3,000 to $4,000 that was immediately needed, suggesting that FitzGerald raise the money. Falconer had already approached a number of wealthy Toronto men for support, and they in turn suggested that the Dominion government should meet this war-related cost. McGill University had received special grants for war work, so when Falconer asked Borden for a federal grant of $4,500, he noted that no new precedent would be involved.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

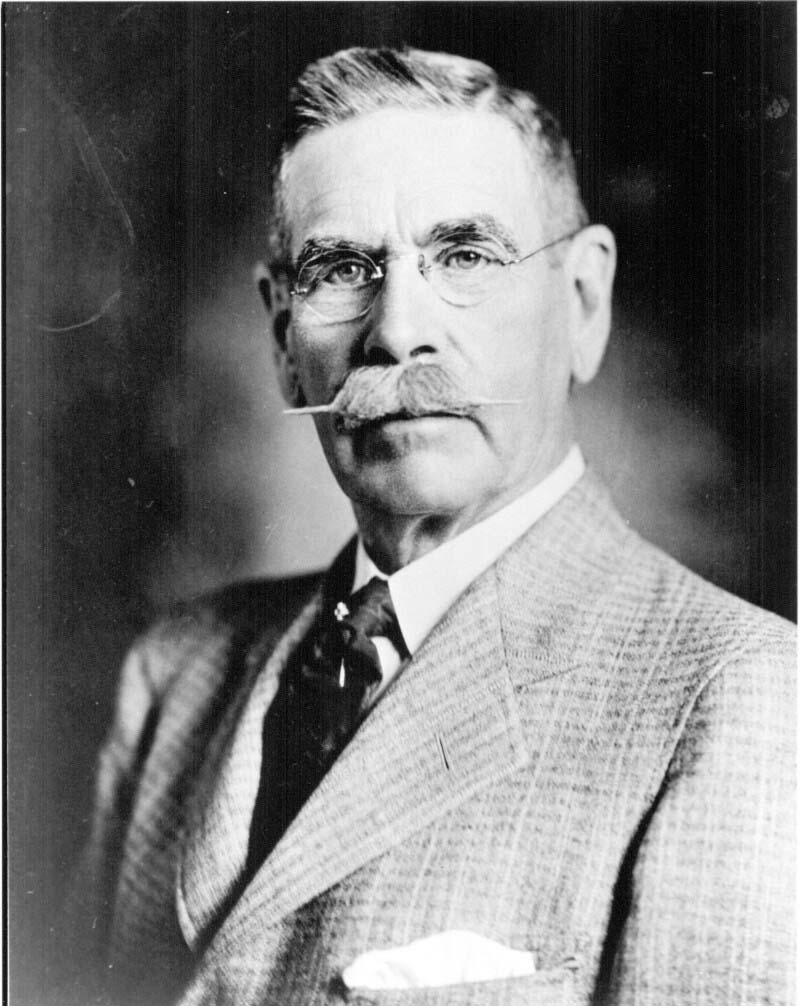

Shortly after Falconer’s appeal to Ottawa, Colonel Albert E. Gooderham—Vice-President of the Gooderham & Worts distillery, philanthropist, and member of the University Board of Governors, as well as chairman of the Ontario Red Cross—met with Falconer. Gooderham immediately wrote a cheque for $3,000, on condition that the funds were to be directed to providing facilities for the preparation of tetanus antitoxin so that a supply was available to the Canadian Red Cross. However, Falconer recognized that he had a potential problem should the Canadian government also grant funds and then discover the Red Cross was given the entire output of antitoxin. A conflict was averted after FitzGerald arranged to immediately supply the Red Cross with 5,000 packages of antitoxin that he was able to purchase from the New York City Health Department at a special reduced price. In the meantime, Gooderham's gift would be used to equip the Antitoxin Lab for producing a Canadian supply by August of 1915. By this time, Gooderham had also offered a much more valuable gift in support of FitzGerald's enterprise. In March 1915, Falconer suggested that Gooderham visit FitzGerald to learn more about his plans. After a 90-minute discussion, FitzGerald showed Gooderham around the Lab’s Medical Building facilities, including a boiler room in the basement, where he planned to stable a few tetanus antitoxin horses. Gooderham did not think much of that idea and suggested, "I suppose for twelve or sixteen thousand dollars it would be possible to purchase a few acres of land on Yonge Street and build a stable and some laboratories there."[iv]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

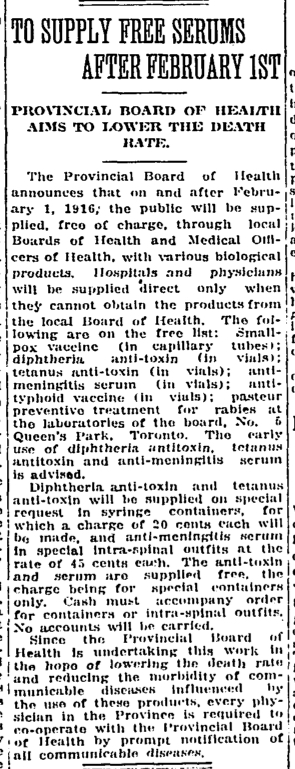

[The Globe (Jan. 7, 1916), p. 7]

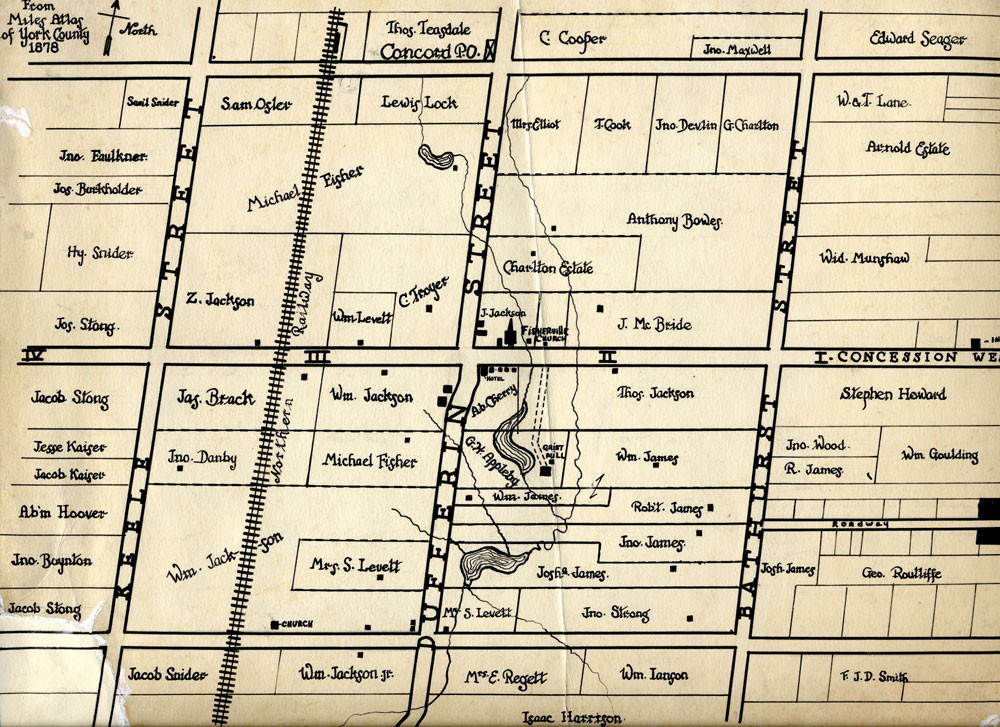

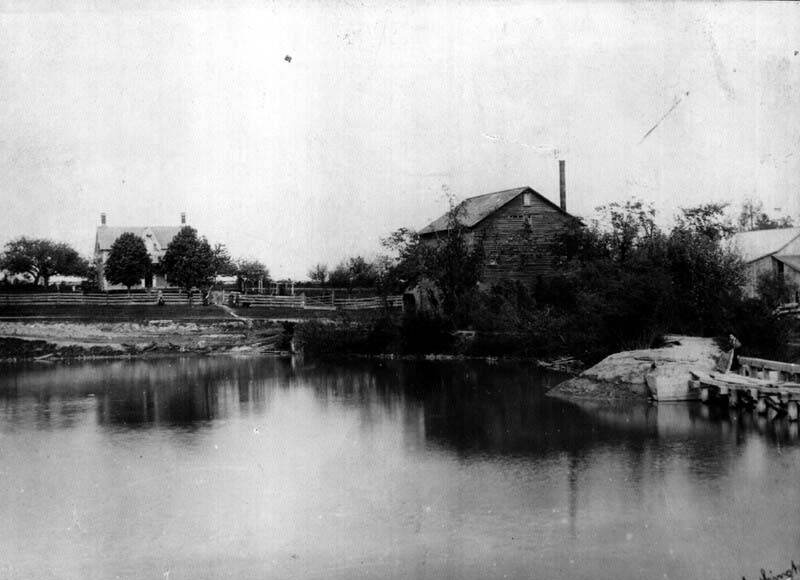

A few days later, Gooderham asked FitzGerald to meet him at the offices of the architectural firm Stevens & Lee, to review preliminary sketches of the laboratory and stable buildings, which Gooderham offered to build once a suitable site was found. Then, in early April, Gooderham took FitzGerald on a drive north into York Township. Gooderham’s real estate agent had heard about a possible site on the York-Vaughan town line at Dufferin Street, in the village of Fisherville. FitzGerald and Gooderham found a long derelict 56-acre farm property that included a farmhouse, barn and a disused mill. FitzGerald was impressed, and Gooderham asked his agent to track down the owners and find out their price, but told him, "Don't let them know that I am interested in it."[v] While plans for the new buildings were finalized and construction proceeded, diphtheria antitoxin was being distributed across the country. In June 1915, FitzGerald stressed in his second Annual Report to the U of T Governors that "The support accorded the laboratory has greatly exceeded the most sanguine expectations, and its place in the scheme of public health activities is Canada made manifest."[vi] In February 1916, the Ontario Board of Health began to distribute the Antitoxin Laboratory’s products for free across the province, and other provincial governments soon followed suit, starting in Saskatchewan.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

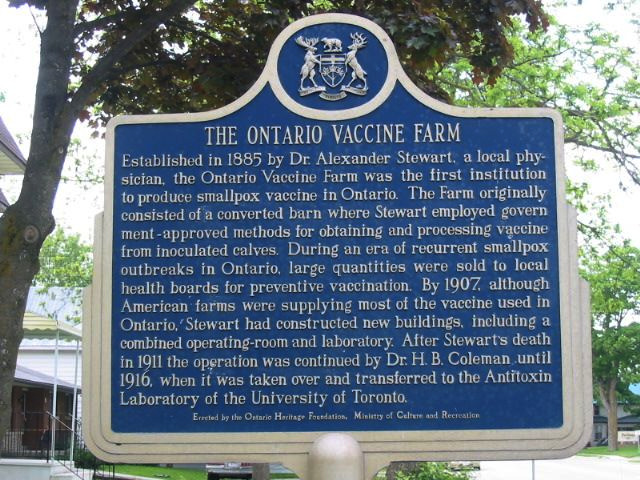

Also in early 1916, the Antitoxin Lab acquired the cattle stock and remaining smallpox vaccine supply from the Ontario Smallpox Vaccine Farm, which had been operating in Palmerston since 1885. Domestic and military demand for smallpox vaccine had grown beyond the capacity of the Vaccine Farm and similar small producers in Canada, and the new lab facilities would enable a larger and higher quality vaccine supply for national domestic and military distribution. By the fall, the new lab on the farm property in Fisherville was completed and largely occupied, and its small staff focused on an expanded level of antitoxin and vaccine production for the war effort and the home front.

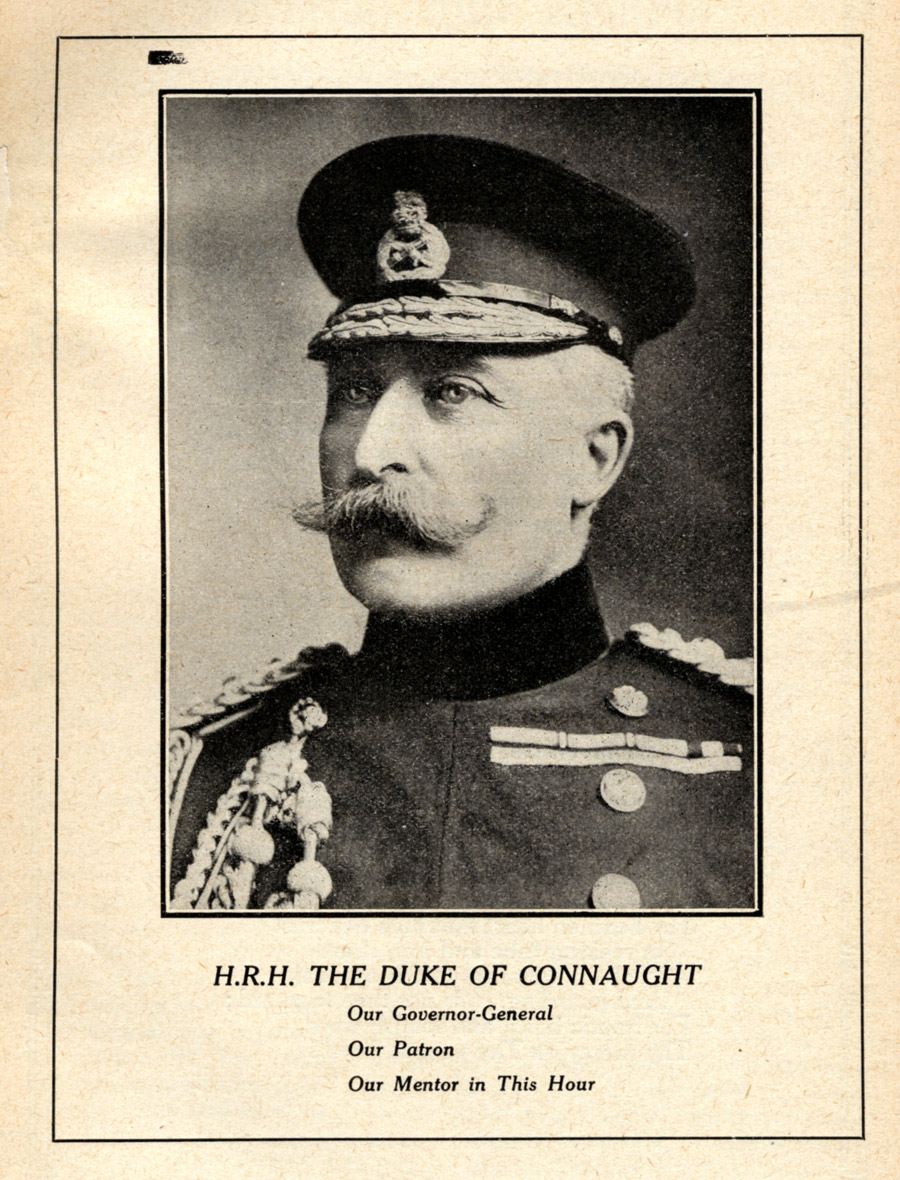

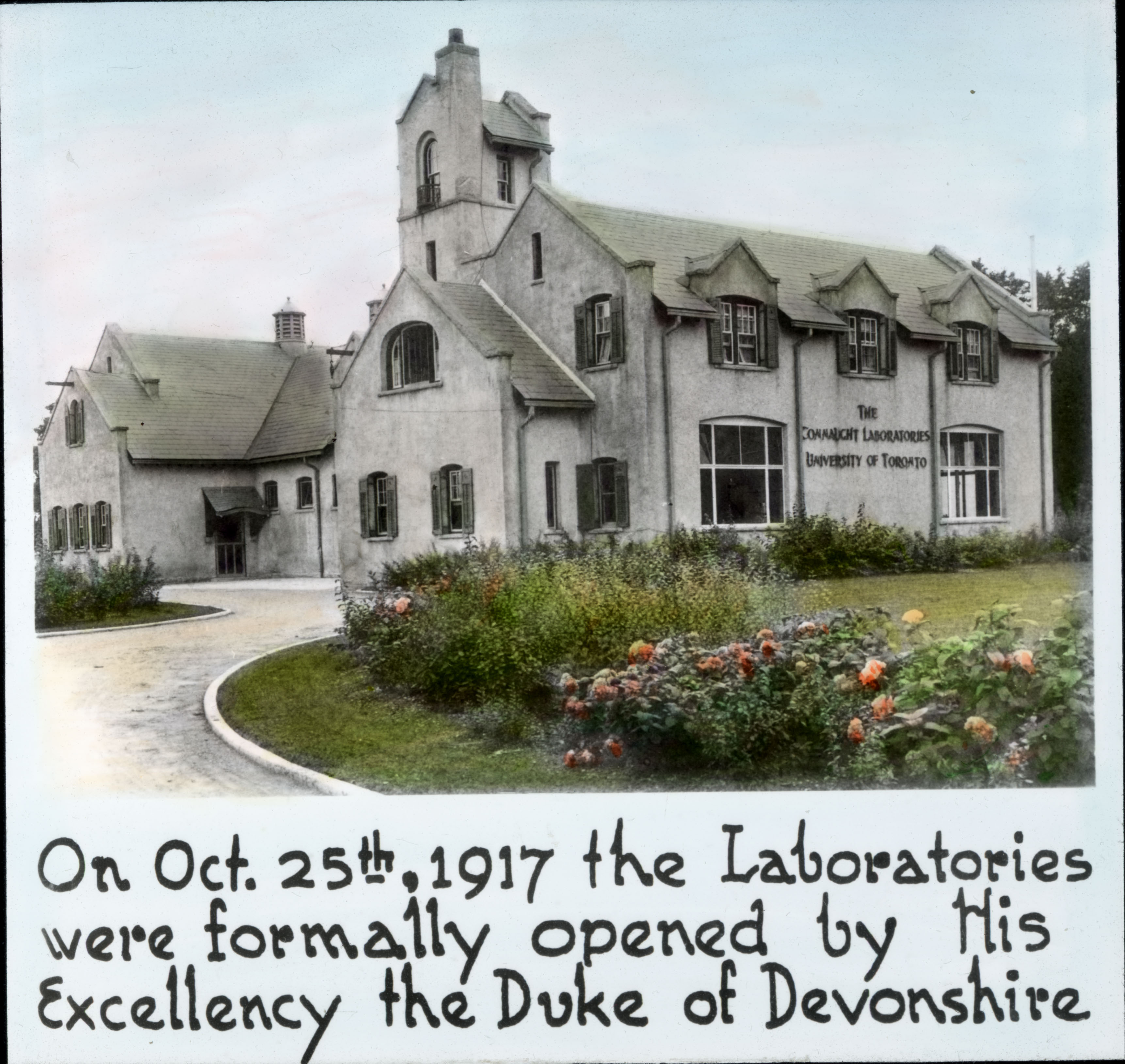

However, the new facility was not ready to be formally handed over to the University until October 25, 1917, which happened to be Gooderham's wedding anniversary and a convenient date. During the months leading up to the official opening of what was to be christened "Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories and University Farm"—named after the Duke of Connaught (Queen Victoria’s 7th child, Prince Arthur), Canada’s Governor General from 1911 to 1916—FitzGerald was focused on securing more autonomy for the Labs within U of T. The Director was given full authority over the Labs’ staff and over the "Connaught Laboratories Research Fund," to which all surpluses from the sale of products were segregated from general University funds and directed to the support of research in preventive medicine, especially product improvements, providing new products, and in facility expansion. Finally, so that Connaught Labs might provide a truly national public health service, an Honorary Advisory Committee of the Connaught Laboratories was established in 1918. Representatives of each provincial government health department and the federal government were appointed to this Committee to meet annually to consult with FitzGerald in regard to scientific problems in which the Labs could be of service.

[Canadian Public Health Journal (Sept. 1914), p. 562]

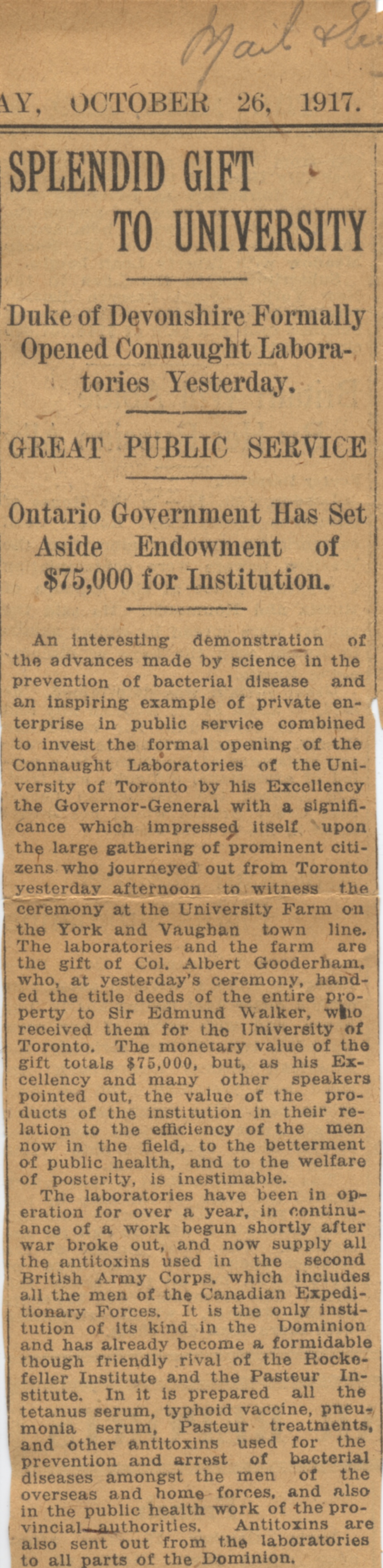

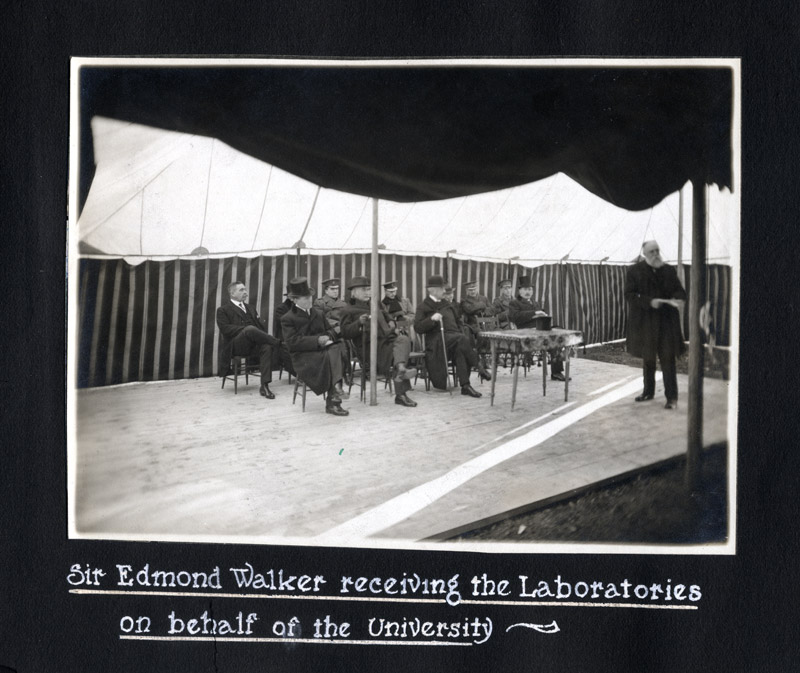

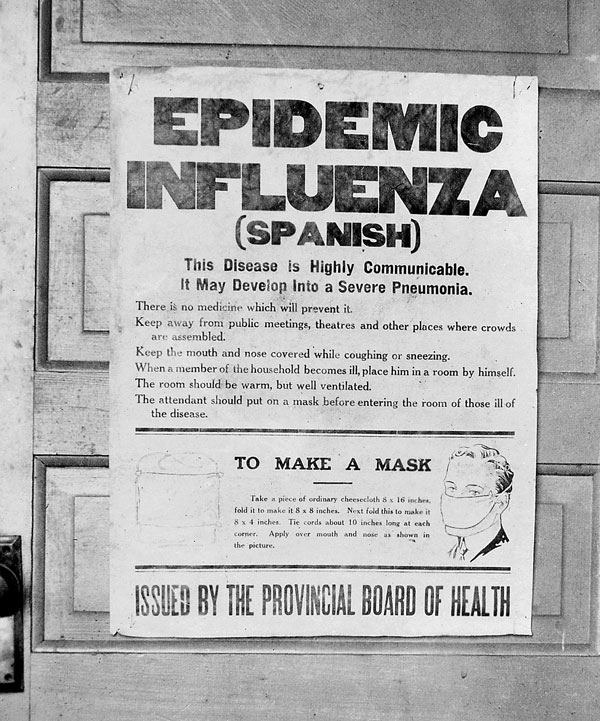

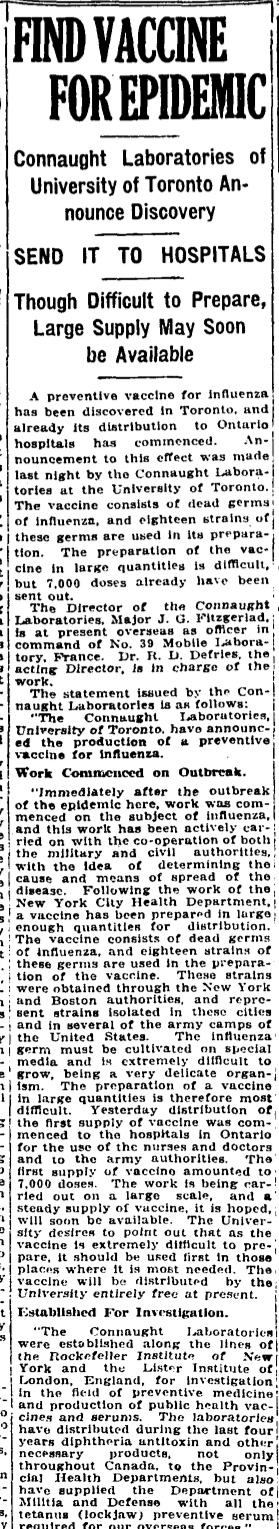

Despite the rainy day on October 25, 1917, the dignitaries and others in attendance on the covered stage set up next to the new laboratory building had their spirits lifted by the Premier’s announcement that the Ontario Government would contribute a $75,000 endowment towards the Connaught Research Fund. Gooderham also announced a further gift of $25,000 for research at the Labs. When asked by reporters why the University was involved in such an unusual manufacturing enterprise, Sir Edmund Walker, Chairman of the Board of Governors, explained that "Through the laboratories the university would extend the work it is carrying on as a great instrument of good for the entire community apart from the educational purpose, by way of direct service for the betterment of general conditions throughout the country."[vii] Almost exactly a year later, on the eve of the war’s end, a new public health crisis provided another opportunity for Connaught Labs to be of national service. “Spanish Flu” first emerged in China in early 1918, but news of a rapidly spreading and especially deadly influenza pandemic was first reported in Spain’s uncensored press in May. By October, as the pandemic spread throughout North America, desperate efforts were launched to prepare a vaccine based on suspicions that new strains of Bacillus influenza were responsible (the viral cause of influenza would not be isolated until 1933). The New York City Department of Health prepared such an influenza vaccine and shared its bacterial cultures and production method with Connaught Labs. With FitzGerald serving in France – he had arrived in June 1918 to take charge of a British Army Mobile Pathology Lab - Defries led a small team in the Labs’ original Medical Building facility who worked day and night during two months to prepare large quantities of what he described as an “experimental” vaccine. The vaccine was freely supplied to provincial health departments, hospitals, the military and various health services across the country, as well as to several U.S. states and even to Great Britain, provided careful records were kept to asses its value. Due to this unprecedented emergency, no claims for the effectiveness of the vaccine were made, but it did no apparent harm and the Labs’ efforts were widely appreciated, helping establish Connaught Labs as a national public health centre in the minds of Canadian physicians and public health authorities.

In the wake of the “Spanish Flu” crisis, much would change in Canadian public health, most notably the much-delayed creation of a federal department of health in May 1919. The new department’s Dominion Council of Health first met in October 1919, with FitzGerald as a key member, its work superseding that of the Honorary Advisory Committee. Also in April 1920, Connaught Labs were granted a U.S. license, and in July the Labs became an Independent Unit within the University of Toronto, overseen by the “Connaught Committee” of the Board of Governors, with Gooderham as its first Chairman.

And on October 31, 1920, down the road in London, Ontario, a young surgeon fresh from military service woke up in the middle of the night with a compelling idea for how to isolate the internal secretion of the pancreas and possibly treat diabetes. That surgeon was Dr. Frederick Banting, and the impact of his idea would prove transformative for the University of Toronto and Connaught Laboratories, a story to be told in the next article in this series.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

Useful Resources:

Bator, Paul with Andrew J. Rhodes: Within Reach of Everyone: A History of the University of Toronto School of Hygiene and the Connaught Laboratories, Volume 1, 1927-1955 (Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association, 1990) Defries, Robert D.: The First Forty Years, 1914-1955: Connaught Medical Research Laboratories, University of Toronto (University of Toronto Press, 1968) FitzGerald, James: What Disturbs Our Blood: A Son’s Quest to Redeem the Past (Toronto: Random House, 2010); details at: http://www.jamesfitzgerald.info Rutty, Christopher J.: “Dr. Robert Davies Defries (1889-1975): Canada’s ‘Mr. Public Health,’” in L.N. Magner (ed.), Doctors, Nurses and Practitioners (Westport, CN.: Greenwood Press, 1997), p. 62-69: available at http://healthheritageresearch.com/Defries-biopaper.html Rutty, Christopher J.: “Personality, Politics and Canadian Public Health: The Origins of Connaught Medical Research Laboratories, University of Toronto, 1888-1917,” in E.A. Heaman, Alison Li and Shelly McKellar (eds.) Figuring the Social: Essays in Honour of Michael Bliss (University of Toronto Press, 2008), p. 273-303; available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/Rutty-ConnughtOrigin-BlissEssays.pdf Rutty, Christopher J. (with Sue Sullivan): This is Public Health: A Canadian History (Canadian Public Health Association, 2010), online eBook: https://www.cpha.ca/history-e-book Rutty, Christopher J. (curator): “Vaccines & Immunization: Epidemics, Prevention and Canadian Innovation: The Online Exhibit,” Museum of Health Care, Kingston, ON (launched November 2014): http://www.museumofhealthcare.ca/explore/exhibits/vaccinations/ Rutty, Christopher J. (curator): “Within Reach of Everyone: The Birth, Maturity & Renewal of Public Health at the University of Toronto,” Dalla Lana School of Public Health website feature (launched 2015): http://www.dlsph.utoronto.ca/history/ Rutty, Christopher J (curator): Sanofi Pasteur Canada, “The Legacy Project” (launched January 2016): http://thelegacyproject.ca

Endnotes

[i] Annual Report of Director Antitoxin Laboratory, Year ending June 30, 1914, Sanofi Pasteur Canada (Connaught Campus) Archives (hereafter SP-CA), 83-005-03. Also published in University of Toronto President's Annual Reports. [ii] R.D. Defries to J.W. Flavelle, January 29, 1915, University of Toronto Archives (hereafter UTA), A67-0007, Box 35. [iii] R. Falconer to R.B. Borden, January 30, 1915, UTA, A67-0007, Box 35. [iv] J.G. FitzGerald, Historical Memo, October 1935, SP-CA, 83-001-09. [v] Ibid. [vi] Annual Report of Antitoxin Laboratory, June 30, 1915, SP-CA, 83-005-03. [vii] "Splendid Gift to University," Mail & Empire (October 26, 1917).