The previous article in this series ended with representatives of the Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Board visiting the University of Toronto in the fall of 1923 to meet with Dr. John G. FitzGerald, Director of Connaught Laboratories. The Foundation was looking to fund a third school of public health, following those it had already funded at Johns Hopkins and Harvard Universities. In the wake of the discovery of insulin—and with the university’s leadership in public health, especially through the work of the Connaught Labs—FitzGerald was confident U of T would be the ideal home for this new school. The School of Hygiene was officially approved by the Rockefeller Foundation in May of 1924 and opened its doors in June of 1927. In the meantime, the Connaught Labs carried out further research and innovations in the development and production of insulin, and also began pioneering work on the prevention of diphtheria, culminating in successful field trials of diphtheria toxoid by the end of the decade.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives; University of Toronto Library (UTL), Insulin Digital Library]

In February of 1924, formal work on a School of Hygiene began with a preliminary proposal by FitzGerald, outlining its organization. He presented the proposal to the Connaught Committee, which then passed it to the Board of Governors for consideration. By this time, the name of the laboratories had changed from the “Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories” to simply “Connaught Laboratories.” The broadening of the Labs’ work and the rapid expansion of its insulin production were reflected in the value of the Connaught Research Fund, which was worth $135,000 in the fall of 1923 (or about $1.95 million in current Canadian dollars),[1] including $25,000 from the Labs’ operating surplus. As the head of the Insulin Division, Charles Best also benefited from Connaught’s growth, receiving a significant raise from $1,200 to $2,000 per year.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives; UTL, Insulin Digital Library]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives; UTL, Insulin Digital Library]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives; UTL, Insulin Digital Library]

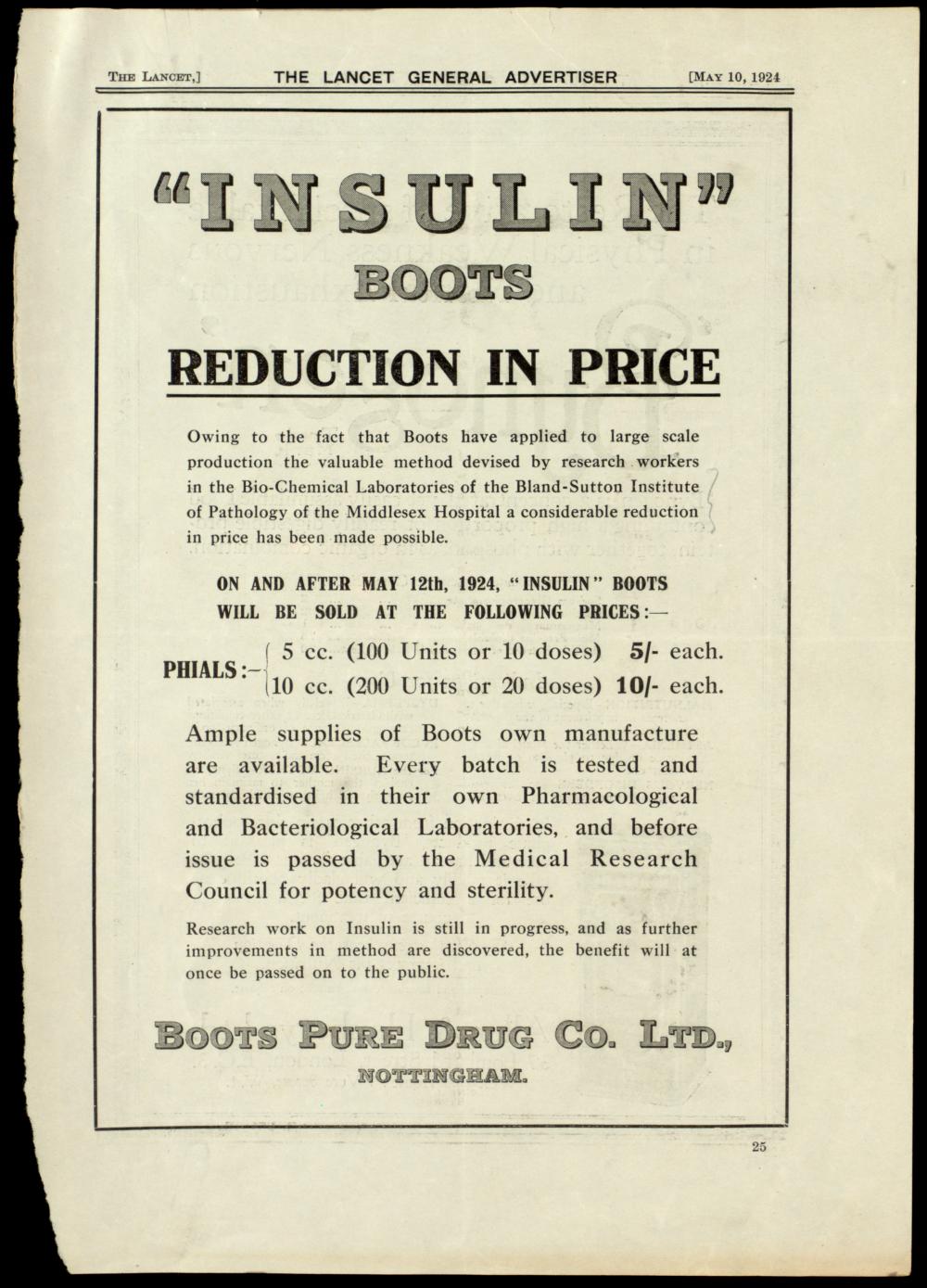

During the early months of 1924, while Connaught’s insulin production continued to grow, reaching 200,000 units per week, the Labs sought to ensure that the price of insulin was kept as low as possible, a key component being the price of beef and pork pancreas tissue charged by meat packers. A steady reduction in price reflected the lower production costs as the Labs’ efficiency improved; the price per 100 units of insulin fell from $2.00 in June 1923, to $1.50 in November, to $1.00 in April 1924. However, for American commercial firm Eli Lilly & Co., ultimately needing to generate a profit, the price issue was more complex, driven by the pending introduction of insulin into the U.S. market by several competing pharmaceutical firms. There was also concerns that meat packing companies could also produce insulin themselves and at a lower cost. G.H.A. Clowes, Lilly’s Director of Research, made his pricing plans clear to the Insulin Committee, which regulated when additional insulin suppliers were able to proceed with distribution. On January 29, 1924, Clowes told the Secretary of the Committee that Lilly was prepared to sell its insulin below cost for months if need be, using it as “a wedge” for its other products. There was a particular concern that the new competitors could bring their Insulin to the market at a price lower that Lilly’s prevailing price.[2]

[UTL, Insulin Digital Library]

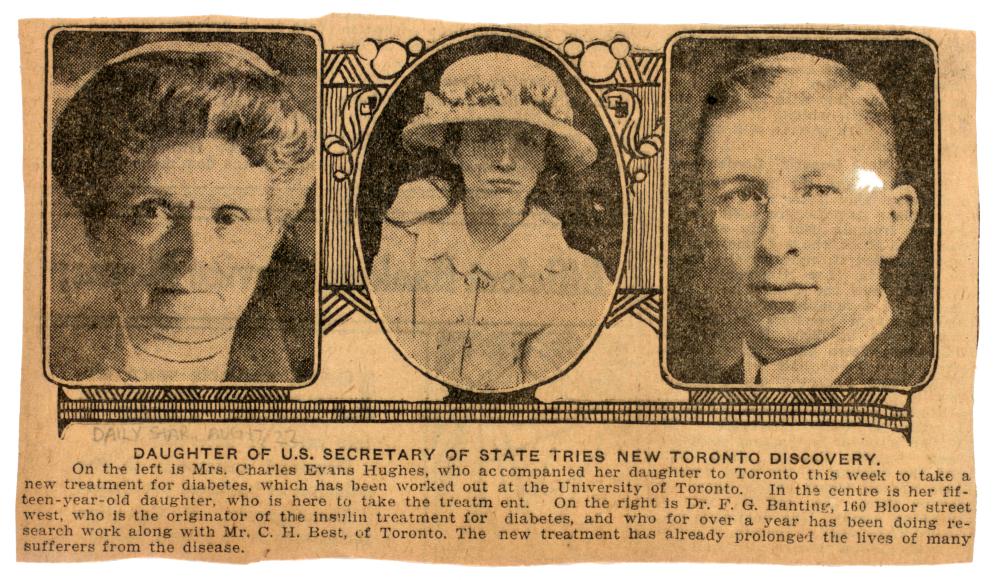

News of reductions in the price of insulin by British manufacturers left Clowes “greatly perturbed,” and he remained concerned about Connaught’s insulin pricing, prompting Associate Director Robert Defries to remind him that, while Connaught would meet current U.S. prices, but not engage in “price fixing”, the Labs’ position as a public service lab was entirely different from that of a commercial firm. Connaught was not, nor would it be, in direct competition with commercial firms in Canada, but in early 1924, as insulin production was also being, or would soon be, established in different parts of the world, price sensitivity was high, especially for Eli Lilly and Connaught as insulin’s pioneering producers.[3] Still, Lilly and Connaught would not be in direct competition, as Lilly’s insulin would not be available in Canada and Connaught’s would not be sent to the U.S., except to treat one notable diabetic case: Elizabeth Hughes, daughter of U.S. Secretary of State Charles Hughes, had come to Toronto in August 1922 as Banting’s private patient and when she returned home, a special arrangement was made to have a supply of Connaught’s insulin sent to her.

[Toronto Star, August 17, 1922; UTL, Insulin Digital Library]

During this period, the Connaught Labs was the world’s primary driver of research and innovation in insulin production. The Labs, as part of U of T, and intimately connected to the U of T Insulin Committee, was ideally placed to freely experiment, innovate, test, apply and share its results. This work was led by Peter Moloney, David Scott, and Charles Best, as reflected in their many scientific publications. Moloney’s research was of particular interest to the press. A Toronto Star article in early January 1924 heralded the discovery of a “New System for Purifying Insulin,” describing how Moloney’s year of research was “Of Immense Value” and would yield a “Much purer, Much cheaper Extract.” Although he remained characteristically “diffident about discussing the new method,” Moloney had presented his work to the American Association for the Advancement of Science. His research, in collaboration with D.M. Finlay, was focused on a new charcoal purification method that built upon their earlier work with insulin adsorption and purification using benzoic acid. While charcoal worked as an effective adsorbent—including adsorption of insulin in pancreatic solution—Moloney’s innovation was based on the process of “replacement,” which, the Star reported, “is effected by shaking the washed charcoal with a solution of benzoic acid in alcohol. The charcoal picks up the benzoic acid and lets go of the insulin.” The extra benzoic acid and alcohol were then separated from the insulin, resulting in the ability to produce larger quantities of insulin of greater purity.[4]

[Toronto Star, Jan. 5, 1924, p. 17]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[The Globe, Feb. 17, 1925, p. 12]

As these developments in insulin production unfolded in early 1924, U of T pressed ahead with its proposal to the Rockefeller Foundation for a school of public health. On May 20, 1924, the Foundation’s International Health Board formally approved U of T’s proposal for financial assistance to establish and endow the School of Hygiene. The next day the Foundation pledged a total of $650,000 towards the construction of a new building and the endowment of two new departments in the School. Connaught’s operating divisions (Antitoxin and Insulin) would be merged to make up the public service section of the new School, a distinctive element not part of any other school of public health. However, public announcement of the Rockefeller gift would not be made until February 1925, by which time it was clear that the Connaught Research Fund would provide the School with a further endowment of $250,000. Increased proceeds from Connaught’s product sales, particularly Insulin, made it possible for a larger endowment than the $135,000 announced in 1923.

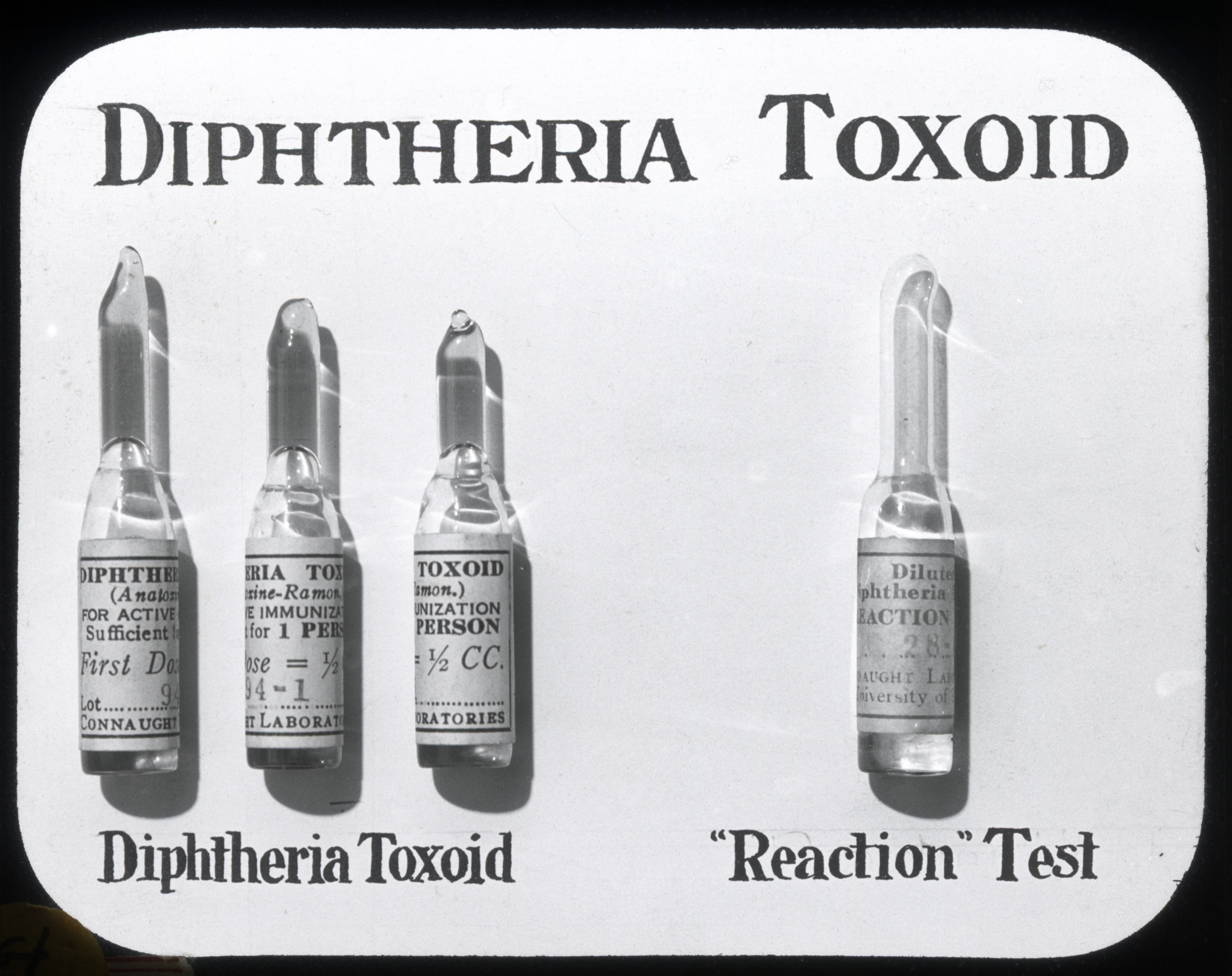

[Public Health Journal, 15 (9) (Sept. 1924), p. 434]

]Wellcome Library[

]https://www.pasteur.fr/en/institut-pasteur[

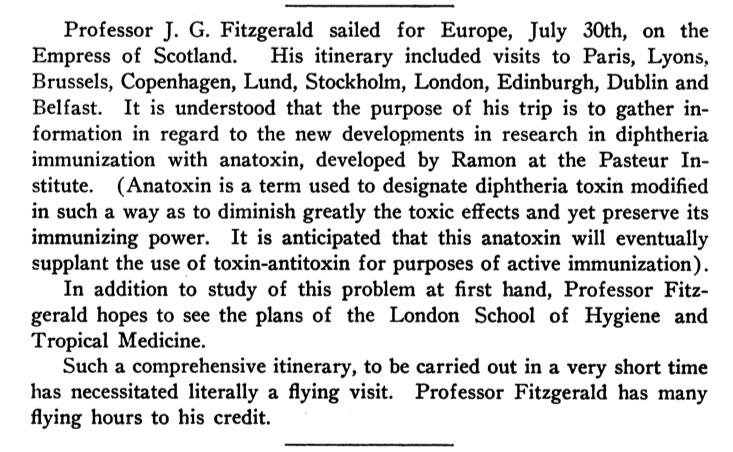

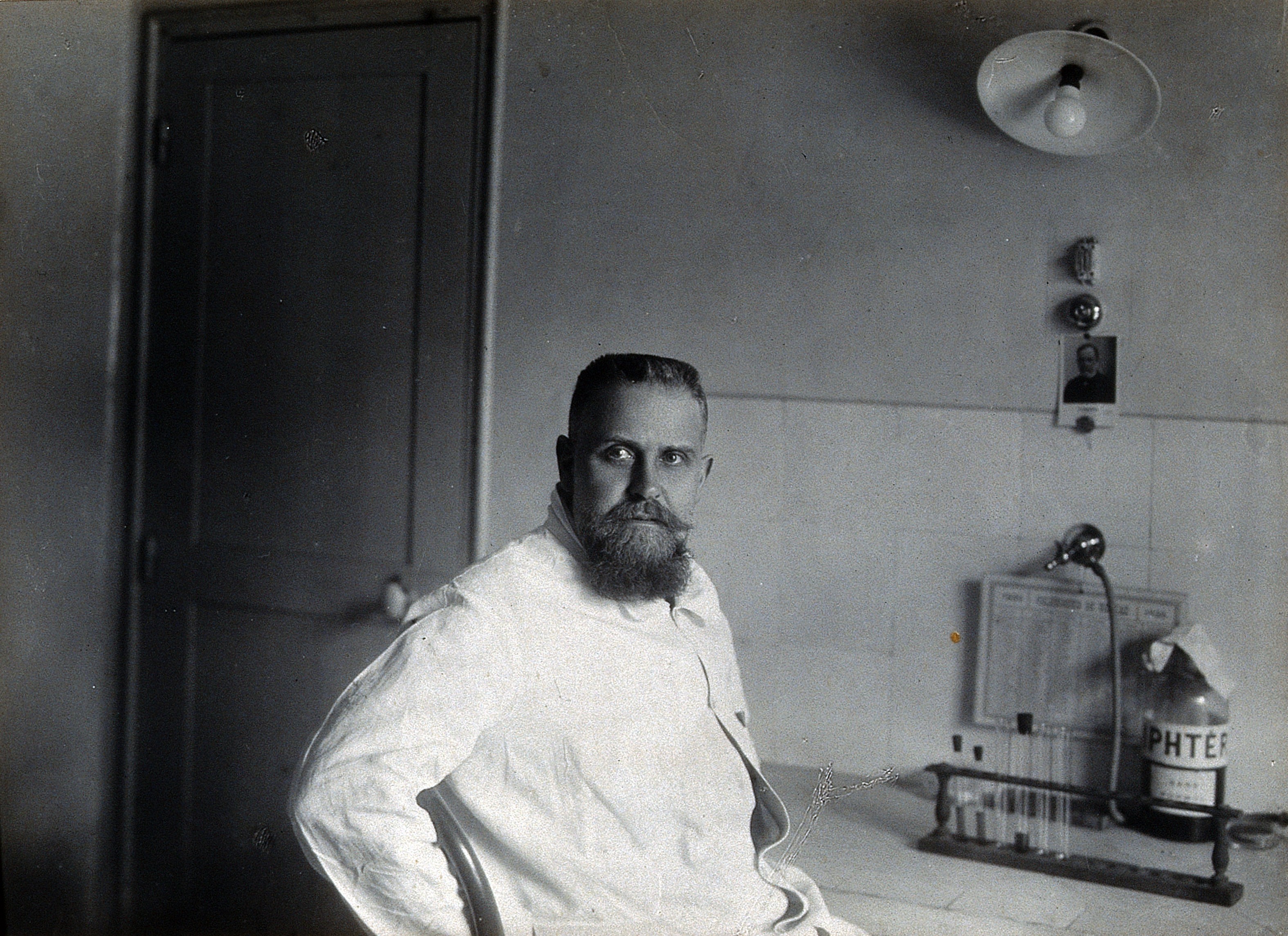

While plans for the new School of Hygiene developed, FitzGerald proceeded with his own plans for extensive travel in Europe, with stops during August and September 1924 in Denmark, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and in France. As discussed with the Connaught Committee, FitzGerald would undertake certain investigations and inquiries on behalf of Connaught, including related to insulin, and to recent research developments with pertussis and diphtheria, and his visit to the Pasteur Institute in Paris would prove to be especially timely. Top of mind for FitzGerald was new research into diphtheria prevention. Although diphtheria antitoxin was freely available to those stricken by the disease, “the strangler,” as diphtheria was known, remained one of the leading public health threats to children under 14. Increasing urbanization, coupled with ease of transmission of the diphtheria bacterium among children kept “the strangler” a major threat. Antitoxin minimized deaths, but did not stop diphtheria’s spread. FitzGerald had heard that the Pasteur Institute’s Dr. Gaston Ramon had recently discovered that treating a potent diphtheria toxin with formaldehyde and heat rendered the toxin non-toxic, and when injected this “anatoxine” or “toxoid,” could safely stimulate active immunity in humans. Ramon was a veterinarian and an expert in diphtheria toxin and the preparation of antitoxin using horses, but he could only test the effectiveness of the “toxoid” in his lab on a small scale. FitzGerald’s visit with Ramon was opportune since Connaught was ideally prepared to facilitate further development and testing of diphtheria toxoid in a much more expeditious way than Ramon could at the time.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

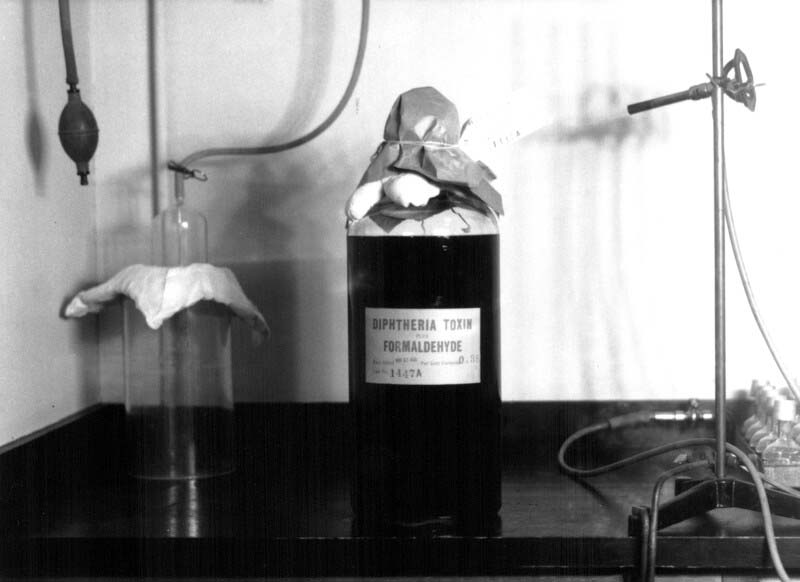

Indeed, FitzGerald was so impressed by Ramon’s toxoid discovery that, from Paris, he cabled Peter Moloney at Connaught; in addition to his insulin work, Moloney was well experienced with handling diphtheria toxin. FitzGerald described Ramon's methods to Moloney and asked him to drop everything and immediately begin preparing and improving the toxoid. Following encouraging initial studies of the toxoid given to a small group of Connaught staff members that showed strong antigenic responses, and similar results among a larger group of children living in an institution, field trials in several cites were launched in September 1925. The trials started in the Essex Border Municipalities near Windsor, Ontario, where some 9,000 pre-school and school-age children received 2 doses of toxoid. A similar toxoid trial took place in Saskatchewan during 1925–26, and by February 1927 a total of some 120,000 individuals in 9 provinces had received diphtheria toxoid. During the initial use of the toxoid, some allergic reactions were reported, prompting Moloney to develop a simple intradermal “reaction test” using a diluted toxoid to detect potential reactors, who were usually older children already immune to diphtheria. This test became known as the “Moloney Reaction Test” and became universally applied.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

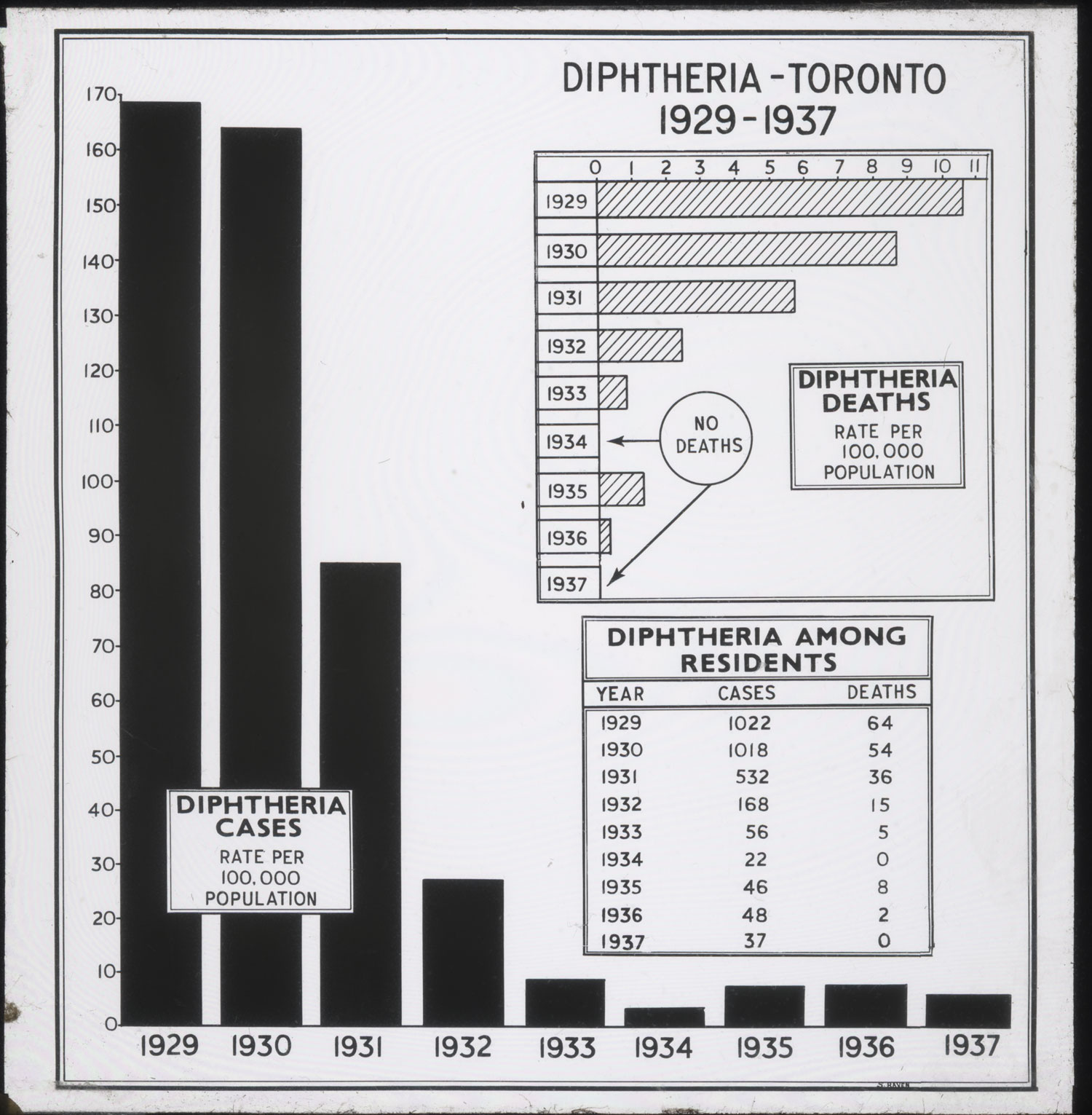

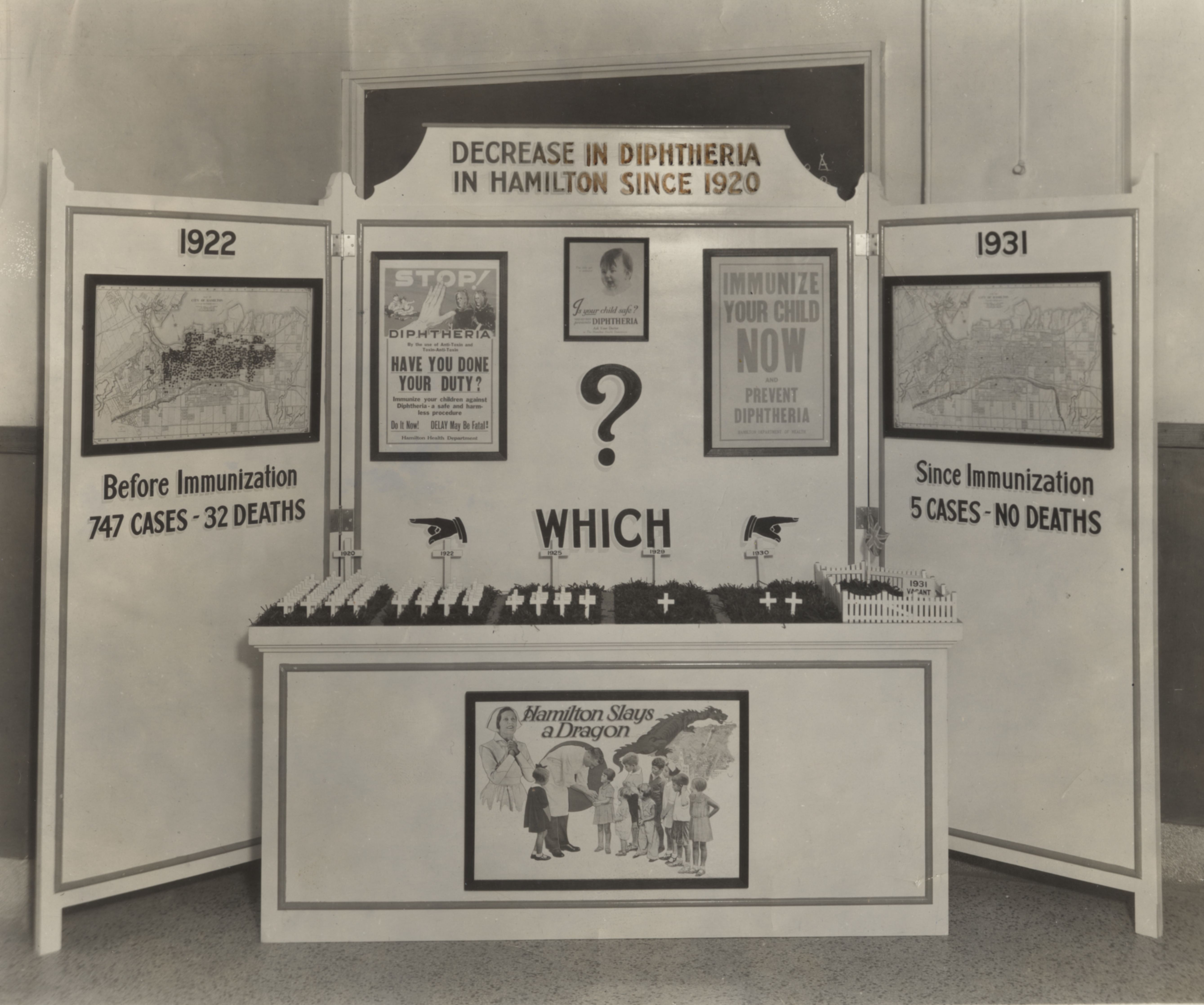

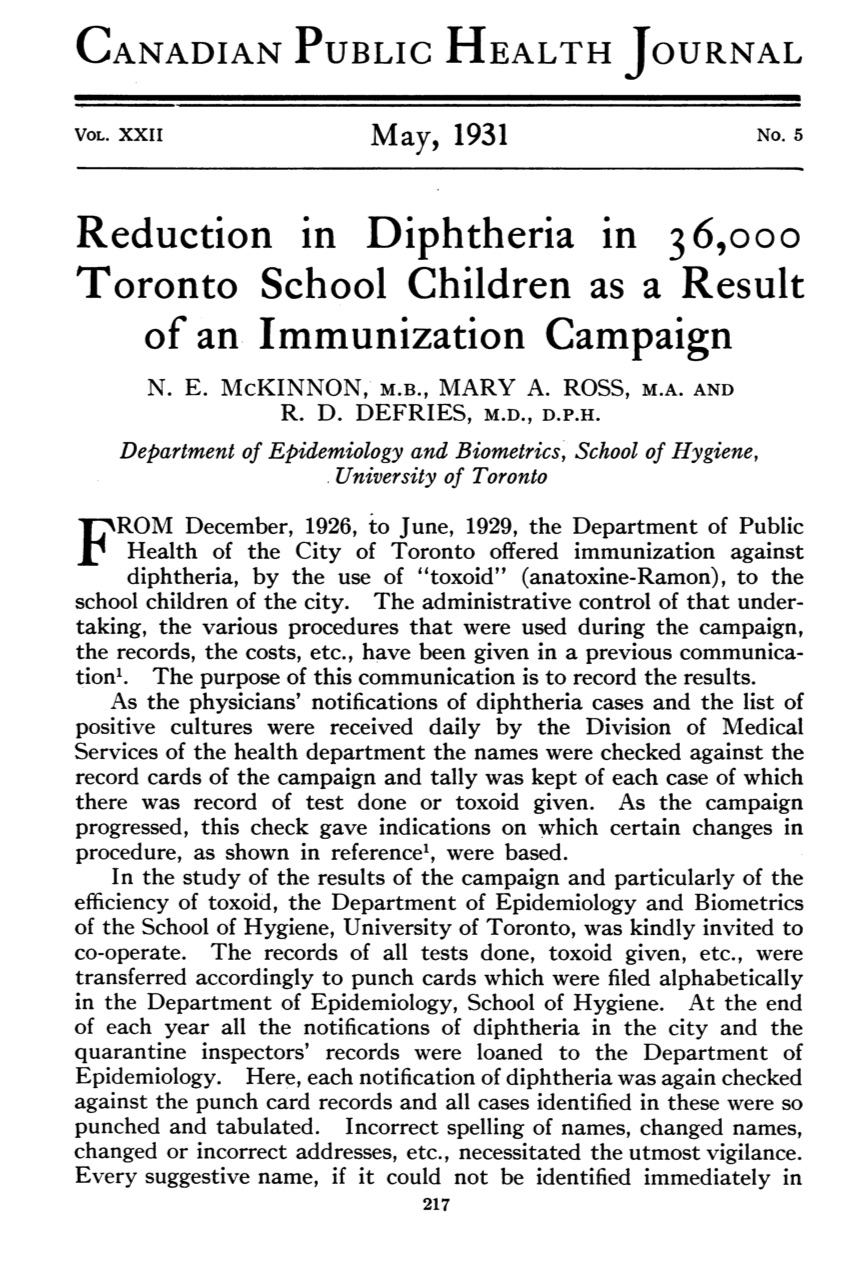

The most dramatic and widely recognized early use of diphtheria toxoid came in Hamilton, Ontario. Thanks to the dedicated leadership of the city’s Medical Officer of Health, Dr. James Roberts, the results in Hamilton were particularly significant, with the toxoid sharply reducing both diphtheria incidence and the number of related deaths. In 1922, there were 742 cases and 32 deaths due to diphtheria in Hamilton, but during 1925–27, once the toxoid was in use, the number of cases fell to 368 with 18 deaths; between November 1, 1926, and September 30, 1927, there were only 10 diphtheria cases and 1 death. “Hamilton Slays a Dragon” was the message of a dramatic and popular public health exhibit produced in early 1932 that showed there were only 5 cases and 0 deaths in 1931. By this time, the results of the most sophisticated diphtheria toxoid field trial were published. This trial took place in Toronto between December 1926 and June 1929, and involved some 36,000 children. The trial conclusively demonstrated that the toxoid reduced diphtheria incidence by at least 90% among those given three doses. This remarkable rate of effectiveness was maintained in Toronto and across Canada into the 1930s, but American and British public health authorities were not yet as enthusiastic. In the U.S. there had been an emphasis on a mixed diphtheria toxin-antitoxin product that had a similar immunizing effect, although such a mixture was inherently risky. In the U.K. there was a more locally focused and conservative approach to public health and to new vaccines. However, the Canadian results, particularly the use of the “Moloney Test”, were not well known outside of the country until FitzGerald and others from Connaught reinforced their published results personally.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Canadian Public Health Journal 22 (5) (May 1931), p. 217]

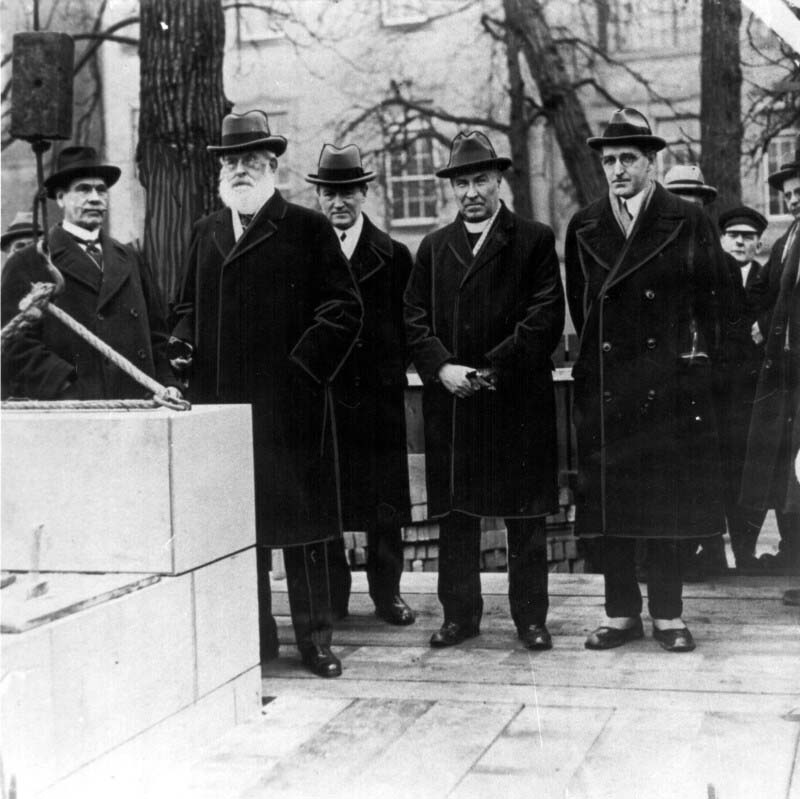

In the midst of the Toronto diphtheria toxoid trial, construction of the School of Hygiene Building was finally completed, along with plans for its official opening on June 9, 1927. The new building would contain the Department of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine (which was shared with the Faculty of Medicine and the School of Graduate Studies), along with a new Department of Epidemiology & Biometrics and a new Department of Physiological Hygiene, both of which were established with endowments from the Rockefeller Foundation. The new building would also house the Department of Public Health Nursing and the offices of the Canadian Public Health Association. Connaught’s main research and production facilities were integrated into the Hygiene Building, with the School and the Connaught Labs overseen by a single administration led by FitzGerald as Director. Indeed, at the official opening, the Chair of U of T’s Board of Governors, Canon Cody, underscored that it was FitzGerald’s idea that the various activities of the School and Connaught should be accommodated under a single roof. Cody said, “Doctor FitzGerald possesses a rare combination of brilliant administrative abilities and an equally brilliant knowledge. In all his work he has been aided by his Chief of Staff, the Associate Director, Doctor R.D. Defries.”[5]

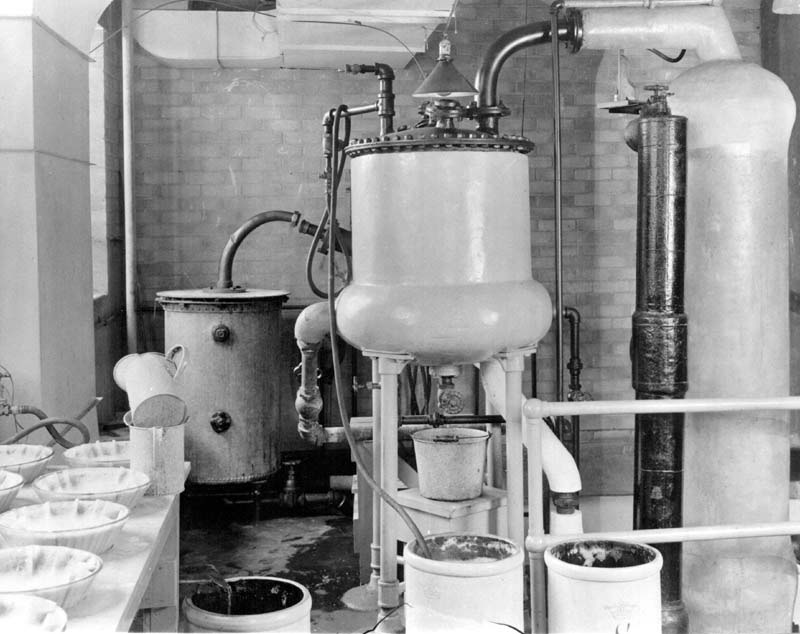

The opening was celebrated with a special event at U of T’s Convocation Hall, followed by a guided tour of the new building led by FitzGerald, Frederick Banting, and Charles Best. Of special interest on the tour was the expanded insulin production facilities located in the basement of the new building, the design of which was overseen by David Scott. Soon after the opening of the School of Hygiene Building, Scott was given a well-deserved sabbatical, which he spent in London, England, both for his honeymoon and to conduct further insulin research in Sir Charles Harington’s laboratory at the University of London. The focus was on the crystallization of insulin, and Scott’s expertise soon paid off when, in 1931, he discovered that the secret to a consistent and large supply of insulin was the addition of small amounts of zinc chloride. This crystallization innovation, based at Connaught, would drive the next stage in the development of insulin during the 1930s, as will be featured in the next article in this series. During the 1930s, Scott and Best would also lead another highly significant story of innovation at Connaught centred on the development of the revolutionary blood anti-coagulant known as Heparin; the details of that story will also follow in the next article.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[The Globe, June 10, 1927, p. 14]

Useful Resources:

Bator, Paul with Andrew J. Rhodes: Within Reach of Everyone: A History of the University of Toronto School of Hygiene and the Connaught Laboratories, Volume 1, 1927-1955 (Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association, 1990)

Bliss, Michael: The Discovery of Insulin (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1982)

Defries, Robert D.: The First Forty Years, 1914-1955: Connaught Medical Research Laboratories, University of Toronto (University of Toronto Press, 1968)

FitzGerald, James: What Disturbs Our Blood: A Son’s Quest to Redeem the Past (Toronto: Random House, 2010); details at: https://www.jamesfitzgerald.ca/

Moloney, Mary V.: Behind Insulin: The Life and Legacy of Peter Moloney; A Man’s Catholic Faith and Bold Science (Toronto: Lulu, 2016); book available via http://www.drpetermoloney.com/

Rutty, Christopher J: “’Couldn’t Live Without It’: Diabetes, the Costs of Innovation and the Price of Insulin in Canada, 1922-1984,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 25 (2008): 407-31; article available at: https://www.utpjournals.press/doi/abs/10.3138/cbmh.25.2.407

Rutty, Christopher J. and Sullivan, Susan: This is Public Health: A Canadian History (Canadian Public Health Association, 2010), online eBook: https://www.cpha.ca/history-e-book

Sanofi Pasteur Canada: “The Legacy Project”: http://thelegacyproject.ca

University of Toronto Library: “The Discovery and Early Development of Insulin” Digital Library; https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/

“Vaccines & Immunization: Epidemics, Prevention & Canadian Innovation: The Online Exhibit,” Museum of Health Care, Kingston (2013-14); http://www.museumofhealthcare.ca/explore/exhibits/vaccinations/

“Within Reach of Everyone: The Birth, Maturity & Renewal of Public Health at the University of Toronto,” Dalla Lana School of Public Health website feature: http://www.dlsph.utoronto.ca/history/

Endnotes: