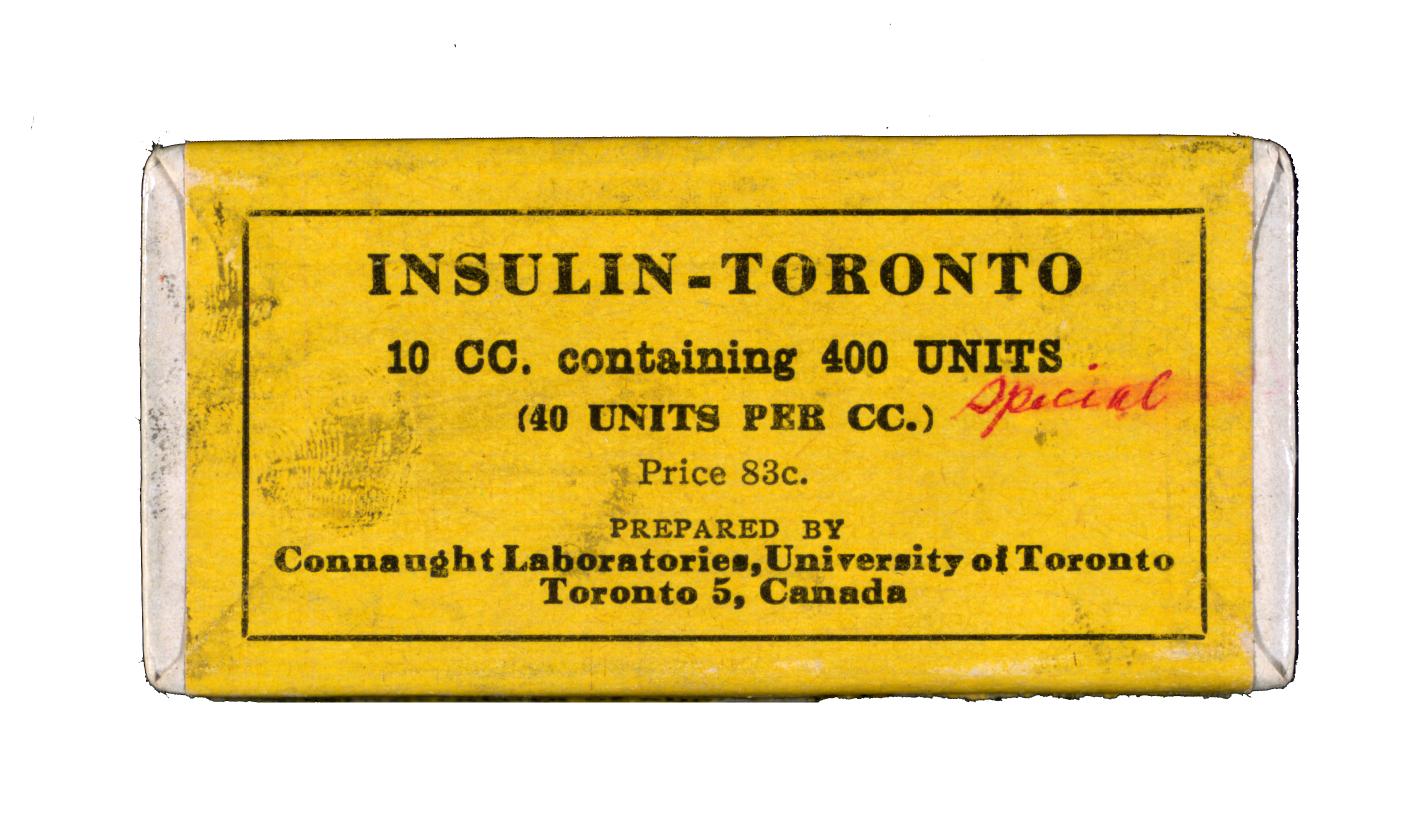

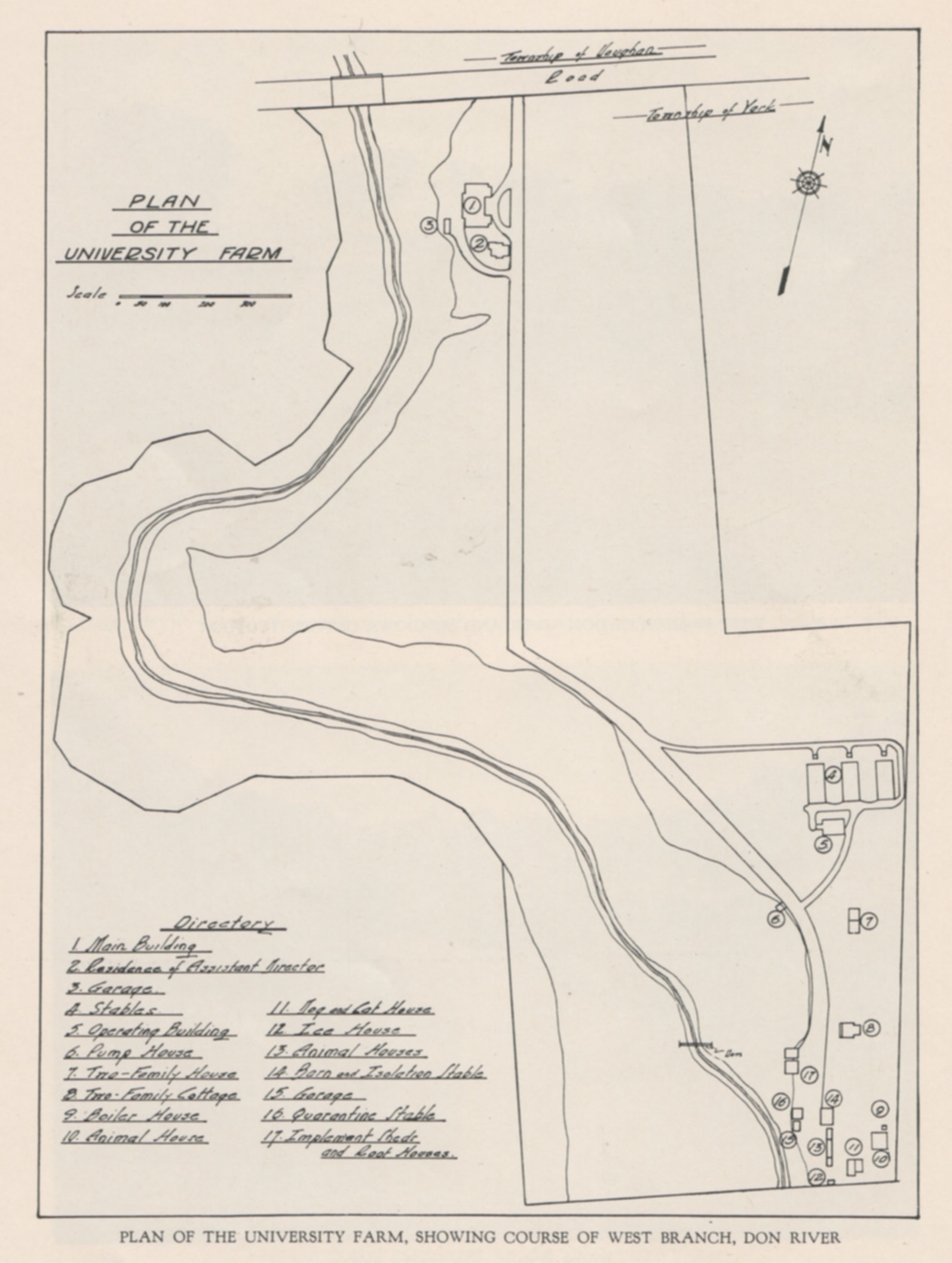

As recounted in the previous article in this series, the latter two-thirds of the 1920s were a highly productive period at Connaught Laboratories, fueled particularly by expanding insulin production, the establishment of the intimately connected School of Hygiene, and major progress towards defeating diphtheria. The start of the Great Depression in 1929 and its worsening economic effects during the early 1930s did little to slow the pace of research and innovation at Connaught. Indeed, the 1930s were a period of rapid physical growth at the Labs, and at the School, and a period of significant scientific advancement, especially in insulin development and production, the experience from which having a direct impact on the Labs’ pioneering work on the development of heparin, “the miracle blood lubricant”. It was not long after the official opening of the School of Hygiene Building in 1927 that it became clear that more space was needed, especially for insulin production. Connaught and the School shared their administration under the Directorship of Dr. John G. FitzGerald, the School serving as the academic research and teaching arm of the Labs and the Hygiene Building also accommodating much of the Labs’ testing and packaging operation, along with the insulin production plant. By the end of the 1920s, it was also clear that additional facilities were needed at the Connaught “Farm” north of the city. Indeed, a construction boom there resulted in five new buildings by 1930, three of which were large stables, another building accommodated animal operating and laboratory facilities, and the fifth was a semi-detached residence for two bacteriologists and their families. One of these resident bacteriologists was Dr. G.D.W. Cameron, who conducted significant studies of diphtheria and scarlet fever antigens at Connaught and later served as Deputy Minister of National Health from 1946 through 1965.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives; University of Toronto Library (UTL), Insulin Digital Library]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

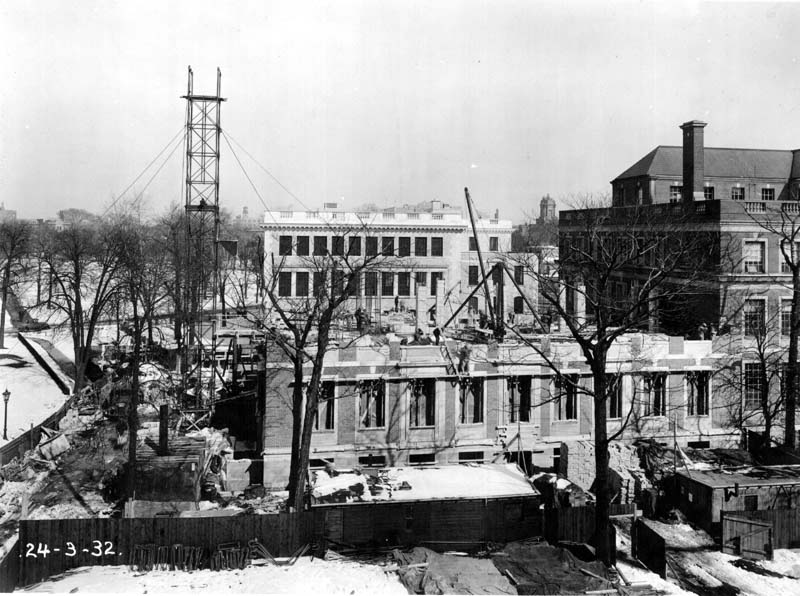

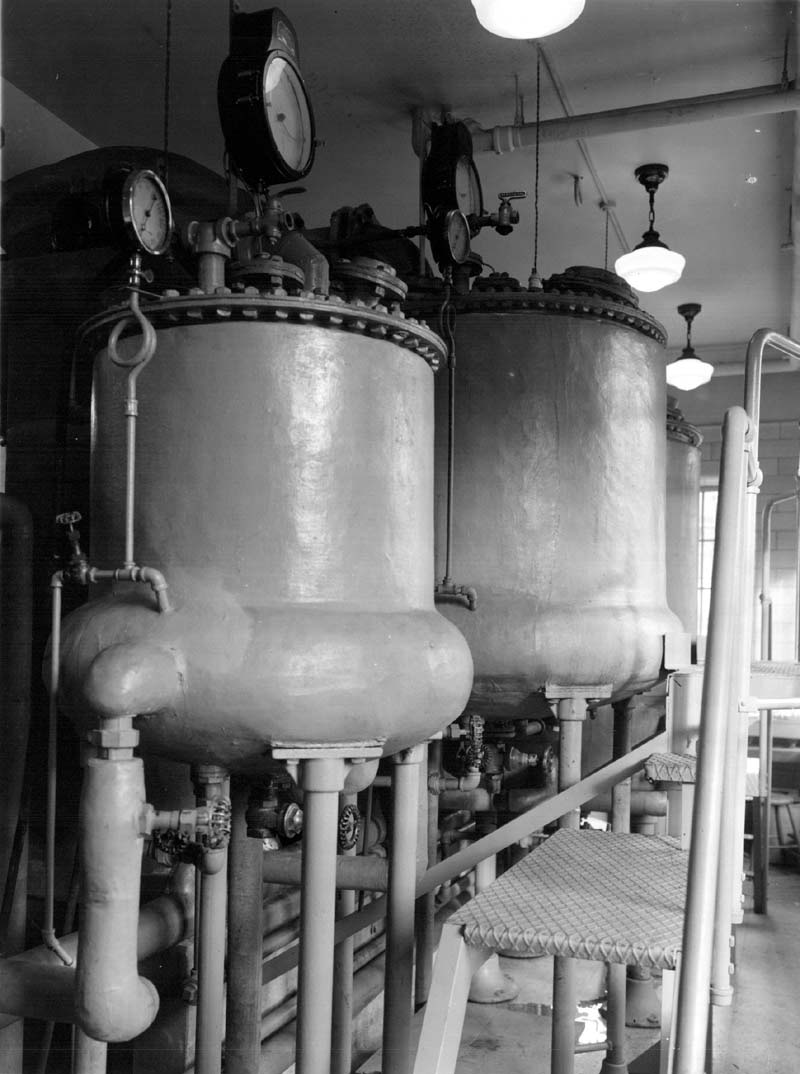

During the early 1930s, the School of Hygiene was at the centre of a remarkable growth industry, exemplified by the building’s expansion, its financing, and the growth of its departments and scope of public health research. Connaught’s Research Fund, derived from the Labs’ accumulated operating surplus, was key to this growth, as it paid for construction, as well as additional research staff and equipment. The Research Fund also helped leverage provincial funding that was dedicated to replenishing the Fund with annual payments, and to facilitate additional funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, which boosted its endowment by $600,000. A northern addition to the School enabled expanded teaching and research facilities, especially for Connaught, while an eastern addition to the south wing accommodated an expanded and more efficient insulin production plant.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

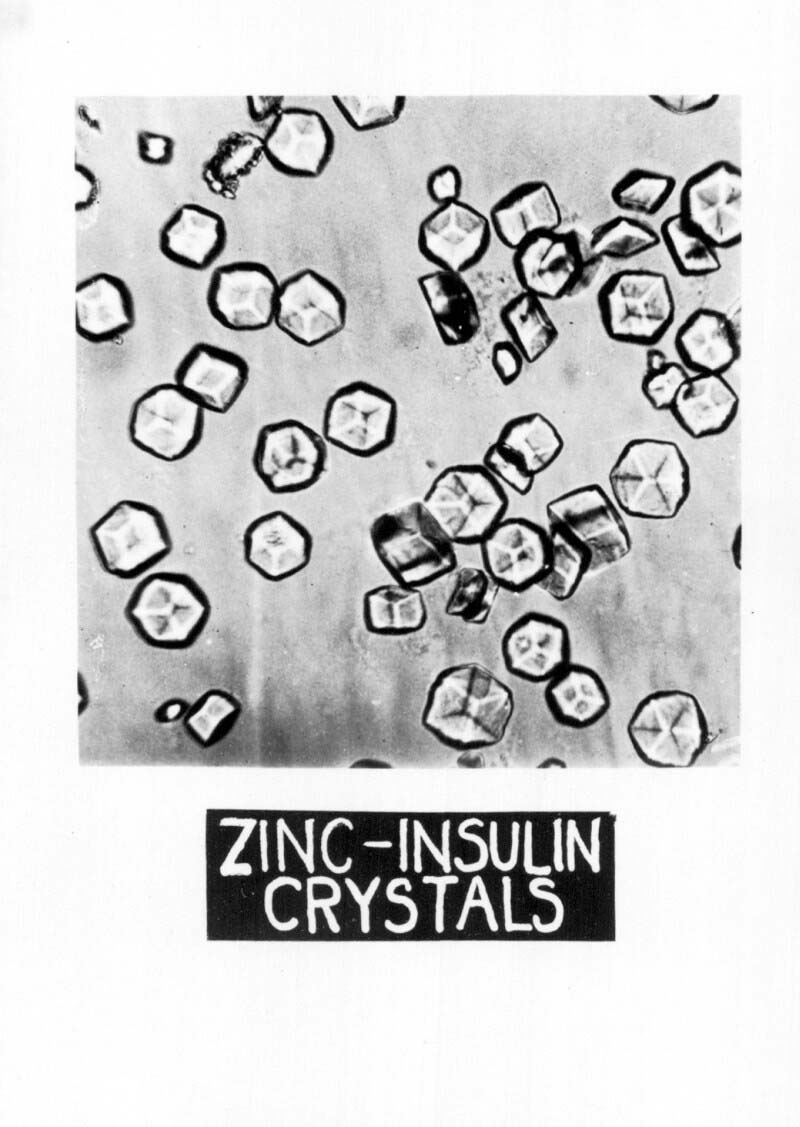

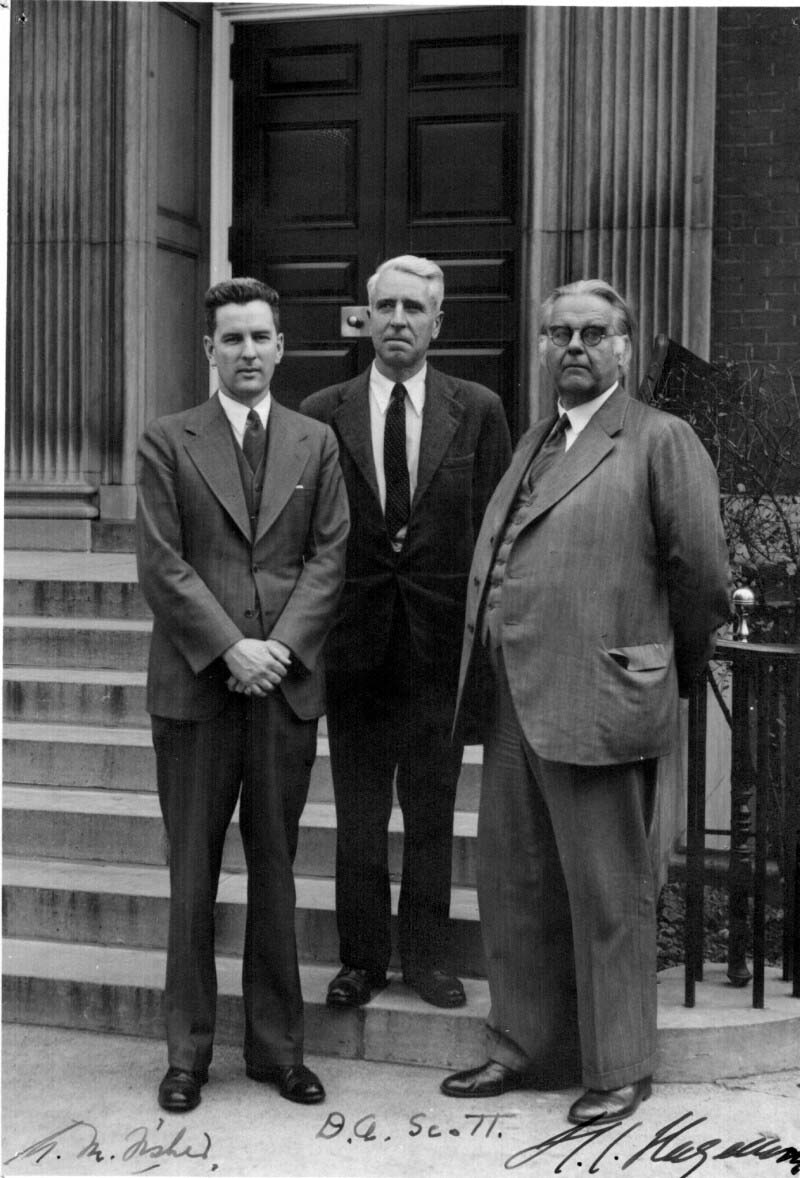

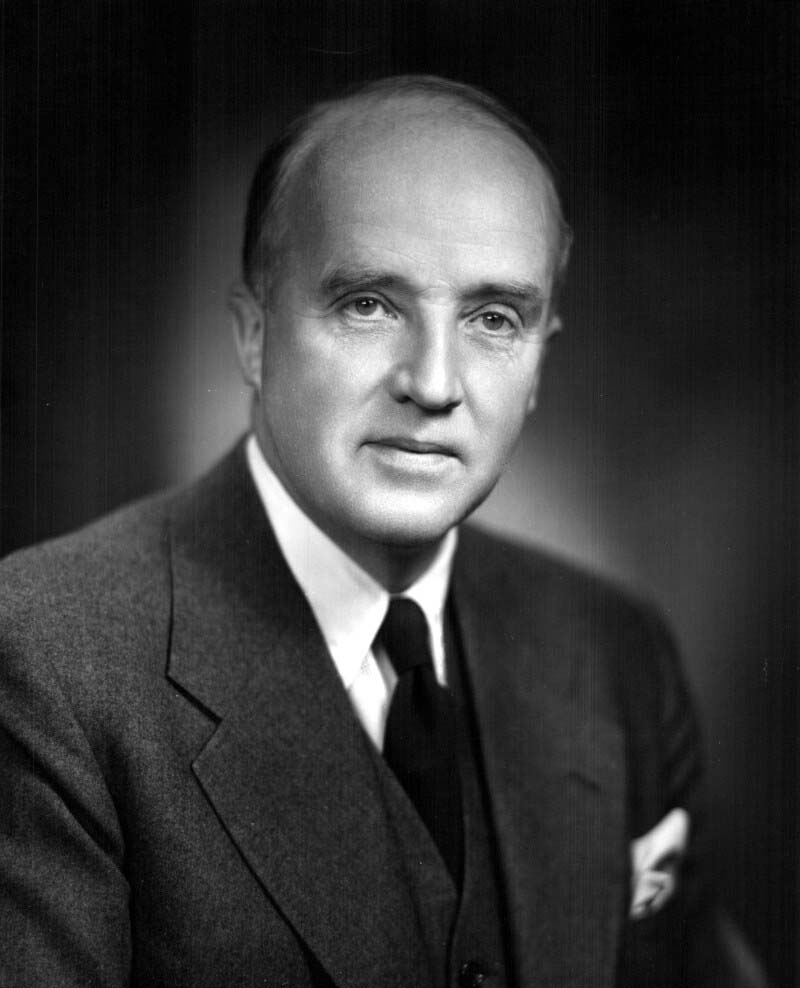

The key to expanded and more efficient insulin production was discovering how to crystalize insulin, and then to figure out how to crystalize it more efficiently. A method to crystalize insulin was discovered by Dr. John J. Abel at Johns Hopkins University in 1926. This method yielded a purer form of insulin, but only in small quantities and it was not as long acting as the original insulin. While Connaught’s Dr. David A. Scott was on a sabbatical at the University of London in 1929, he conducted further studies on insulin crystallization, hoping to build on Abel’s method, yet he remained unsuccessful until he returned to Connaught. In January 1930, Scott tapped into his mineralology expertise and observed that pancreatic tissue contained appreciable amounts of zinc, cobalt and nickel. He then focused on the possible action of zinc in the crystallization of insulin and discovered that the addition of small amounts of zinc chloride to a buffered solution of insulin resulted in the precipitation of insulin crystals. By 1933, through refining this crystallization process with the assistance of Dr. Arthur F. Charles and Dr. Albert M. Fisher, Scott demonstrated that large quantities of highly purified insulin could be consistently produced. At Connaught, Fisher and Charles also prepared a new international standard for insulin, the first in crystalline form.[1]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

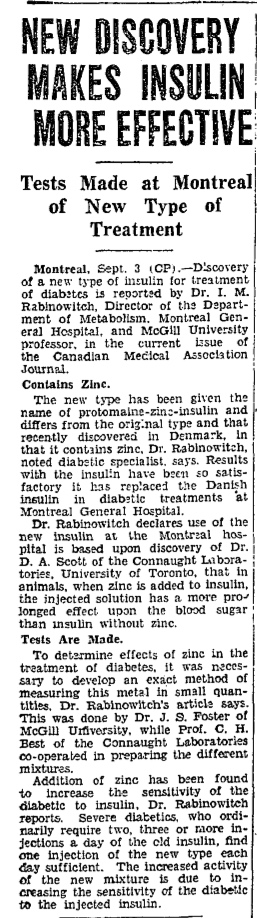

Scott and Fisher would next make a key contribution to solving the long-standing challenge of extending the action of insulin so as to reduce the frequency of injections diabetics required. The first breakthrough was made in Denmark in 1935 at the Nordisk Insulinlaboratorium, where Dr. H.C. Hagedorn discovered that the addition of a small amount of protamine (a substance in fish sperm) to insulin prior to injection slowed the body’s absorption of the insulin and extended its effect. Scott and Fisher quickly built on Hagedorn’s work and discovered that the addition of trace amounts of zinc to the protamine-insulin mixture not only further extended the body’s absorption of the insulin, it also stabilized the protamine-insulin mixture.[2] By the fall of 1936, “Protamine Zinc Insulin” became widely used and was the first long acting alternative to regular insulin.

[The Globe, Sept. 4, 1936, page 2]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

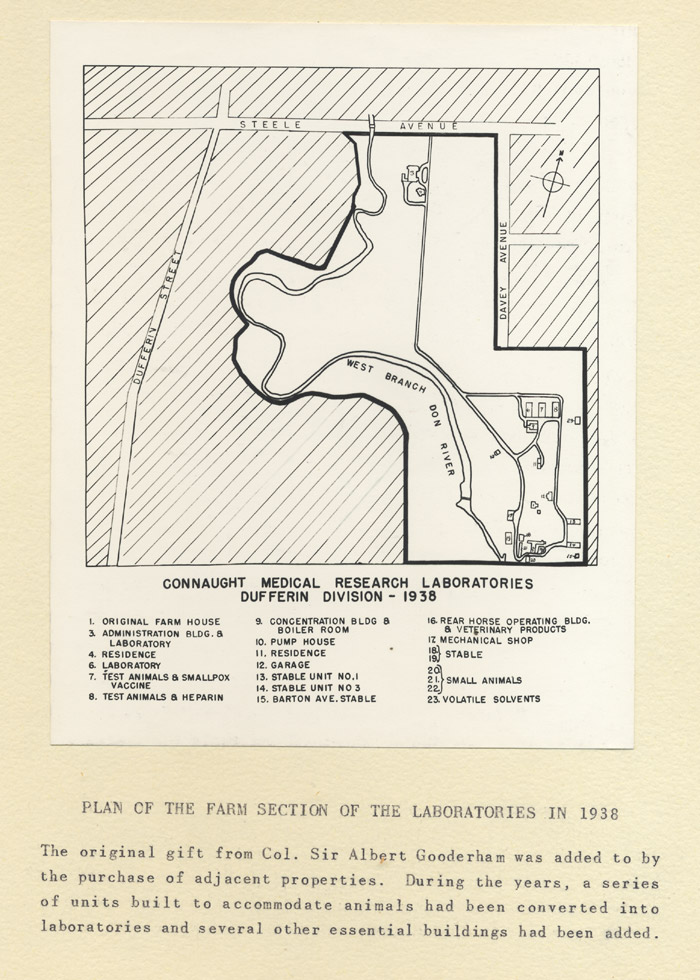

Meanwhile, Connaught’s building boom continued, both at the Hygiene Building and at the Farm site. In particular, a series of extensions in the Hygiene Building were completed, especially in the southeast wing. At the Farm, new buildings were constructed to accommodate horses that moved from the three stable buildings erected in the late 1920s. These new stable buildings were constructed after five acres were added to the eastern boundary of the Farm site. Amidst the Farm’s expansion, the Labs’ original “Barton Avenue Stable” found a new home next to the new stables after it was moved from Barton Avenue in 1935 when threatened with demolition. FitzGerald, was committed to preserving the original stable for its historical significance to the Labs and to public health in Canada. Thus, the stable was disassembled, transported to the Farm, re-built and restored with the goal of a museum being set up inside. However, with many horses on the site, it proved useful again as a stable and the museum plans were put off.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

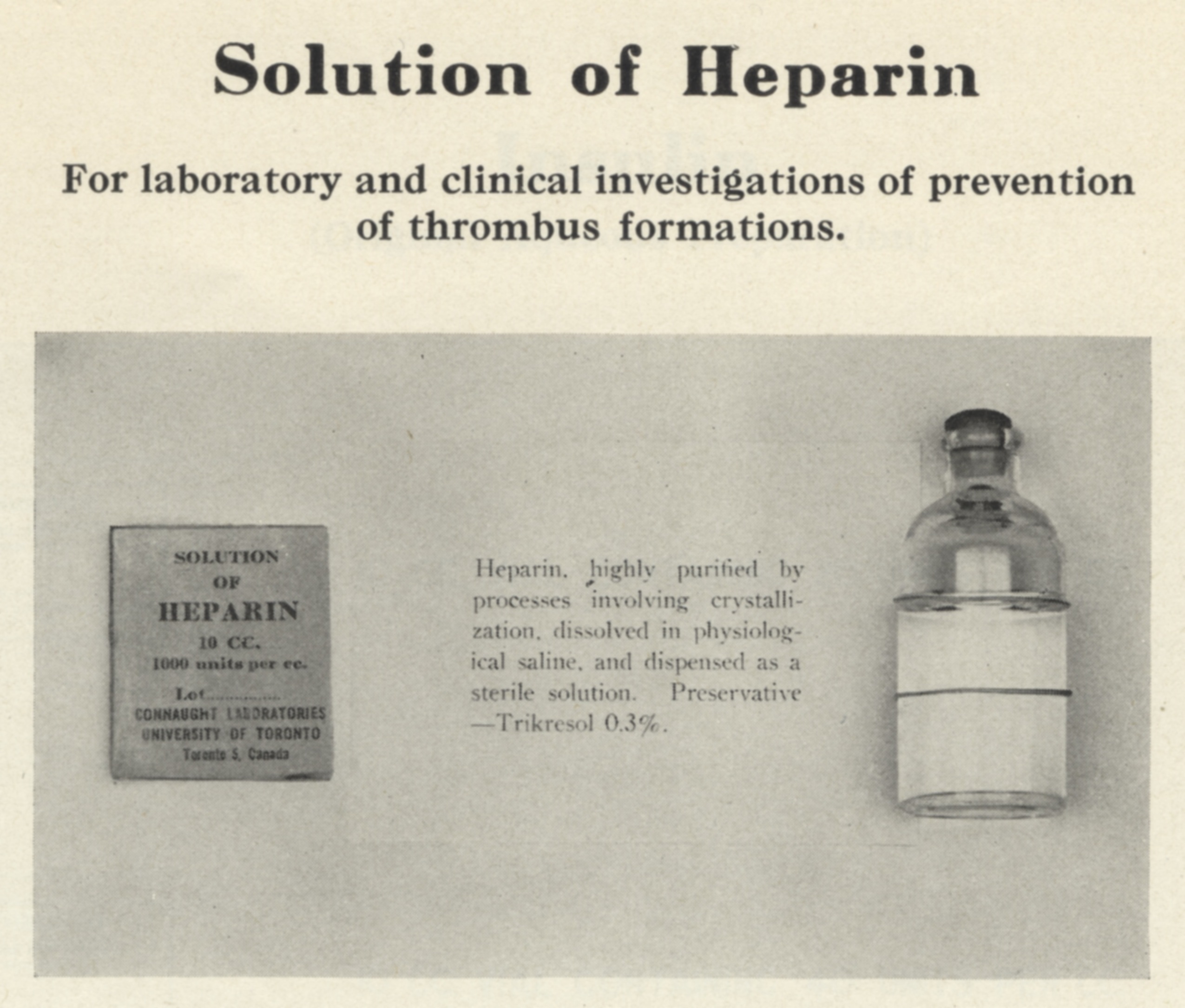

In 1935, the three former stable buildings were converted into new “Laboratory Units” to facilitate expanded production and research work at the Connaught Farm. The first unit accommodated a new bacteriological lab; the second unit was dedicated to smallpox vaccine production on the main floor and a white rat colony on the second floor; and the third unit accommodated a biochemical lab, a guinea pig colony, and a facility for the production of heparin. Heparin is a still mysterious molecule present in various animal tissues and responsible for regulating blood coagulation. Heparin remains mysterious because it does not have an assigned formula and has thus not yet been synthesized; it is composed of more than 100 related substances that cling together as a unit.[3]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

The installation of Connaught’s heparin production facility was the culmination of a research and development effort that insulin co-discoverer, Dr. Charles H. Best, began in 1928. For Connaught Labs and Canadian biotechnology, the development of heparin was a clear sequel to the insulin story, and in many ways its impact proved to be much broader, especially on the development of modern surgery and medical technology requiring the control of blood coagulation.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

Following postgraduate studies in Europe, Best returned to Toronto in 1927 to continue as Connaught’s Assistant Director and to begin his position as Head of the School of Hygiene’s Department of Physiological Hygiene. Among other projects, Best decided to focus on heparin, which had been discovered in 1916 by Jay McLean, then a second-year medical student at Johns Hopkins University, working under the direction of physiologist Dr. William Henry Howell. McLean extracted the anti-coagulating substance from dog liver, but did little further work with it, leaving Howell to continue the research and name it “heparin” (derived from “hepar,” the Greek term for liver). The McLean-Howell heparin could only be made on a small scale and proved to be toxic and of minimal value. However, during his studies in London, Best saw potential in revisiting heparin, based on Connaught’s expertise with insulin production. Best’s two-part research program focused on 1) purifying heparin and then producing it in large but affordable quantities, and 2) studying heparin’s effects in animals and then humans.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

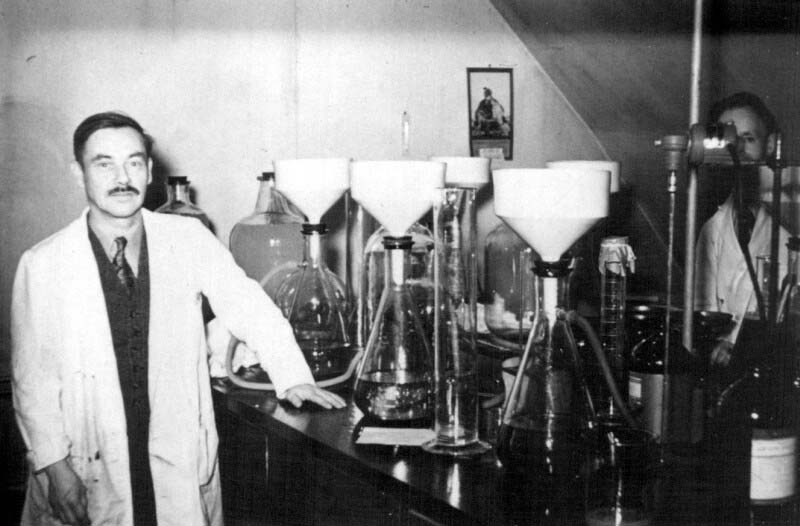

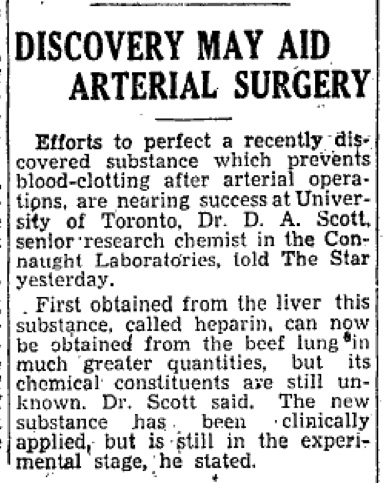

To tackle the first part of the first goal, Best turned to Arthur Charles, a specialist in organic chemistry and Best’s graduate student, who also contributed to Scott’s insulin crystallization research. By 1933, Scott had also joined the heparin project, utilizing his experience with insulin production to devise a method for extracting heparin from not only beef liver, but also lung and intestine tissue on a larger scale. Charles and Scott took advantage of Connaught’s ongoing arrangement with Canadian meat processors to secure pancreas tissues for insulin production in order to gain access to large amounts of otherwise discarded beef organs for the heparin research. In 1933, Charles and Scott published the first papers on their heparin research, which described how the yield of extracted heparin could be doubled if the beef tissues, especially lung, were allowed to autolyse for 24-hours before extraction. However, the potent smell emanating from the autolysing, or rotting tissue, was so offensive that production had to move from the School of Hygiene Building up to the more open environment of the Connaught Farm site.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

By 1936, while studying heparin’s elusive and mysterious chemistry, Charles and Scott developed a method to purify and crystalize the heparin extract into a standardized dry form that could be administered in a salt solution. Heparin in its dry crystalized form thus became Connaught's second product, after insulin, to be recognized as an international standard. Following encouraging results during animal testing, heparin next required testing through clinical studies in a surgical setting. Best turned to Dr. Gordon Murray, a prominent surgeon based at Toronto General Hospital. Murray’s initial experimental surgery with various animals demonstrated that heparin effectively cleared up internal blood clots, and also seemed useful for dangerous operations where blood otherwise coagulated quickly. The first human tests with purified heparin were conducted in April 1937, although a cruder form tested earlier in selected cases revealed encouraging results. The initial trials of heparin involved hundreds of complex surgical cases, in which heparin played an essential and often dramatic life-saving role. It became clear that Connaught’s heparin was a safe, easily available and effective anticoagulant.[4] Best’s heparin team had opened the door to such life-saving operations as organ transplants and open-heart surgery, as well as the artificial kidney, a key piece of medical technology pioneered by Murray. Connaught’s vital contributions to the further development of insulin and also to heparin during the 1930s were clear highlights of an especially innovative decade. However, the end of the decade was marked by the start of another world war, the impact of which changed the course and targets of Connaught’s biotechnology and public health research, innovation and production work, as will be discussed in the next article in this series.

[Toronto Star, Feb. 27, 1936, page 8]

[Globe & Mail, June 14, 1939, page 2]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

Useful Resources:

Bator, Paul with Andrew J. Rhodes: Within Reach of Everyone: A History of the University of Toronto School of Hygiene and the Connaught Laboratories, Volume 1, 1927-1955 (Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association, 1990) Bliss, Michael: The Discovery of Insulin (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1982) Defries, Robert D.: The First Forty Years, 1914-1955: Connaught Medical Research Laboratories, University of Toronto (University of Toronto Press, 1968) FitzGerald, James: What Disturbs Our Blood: A Son’s Quest to Redeem the Past (Toronto: Random House, 2010); details at: http://www.jamesfitzgerald.info Rutty, Christopher J: “Miracle Blood Lubricant: Connaught and the Story of Heparin, 1928-1937,” Conntact (Connaught Laboratories Limited employee magazine) (Aug. 1996); article available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/Heparin-Conntact9608.html Rutty, Christopher J: “’Couldn’t Live Without It’: Diabetes, the Costs of Innovation and the Price of Insulin in Canada, 1922-1984,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 25 (2008): 407-31; article available at: https://www.utpjournals.press/doi/abs/10.3138/cbmh.25.2.407 Rutty, Christopher J. and Sullivan, Susan: This is Public Health: A Canadian History (Canadian Public Health Association, 2010), online eBook: https://www.cpha.ca/history-e-book Sanofi Pasteur Canada, “The Legacy Project”: http://thelegacyproject.ca University of Toronto Library: “The Discovery and Early Development of Insulin” Digital Library; https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/ “Vaccines & Immunization: Epidemics, Prevention & Canadian Innovation: The Online Exhibit, Museum of Health Care, Kingston (2013-14); http://www.museumofhealthcare.ca/explore/exhibits/vaccinations/ “Within Reach of Everyone: The Birth, Maturity & Renewal of Public Health at the University of Toronto,” Dalla Lana School of Public Health website feature: http://www.dlsph.utoronto.ca/history/

Endnotes:

[1] D.A. Scott and A.M. Fisher, “Crystalline Insulin,” Biochemical Journal 29 (May 1935): 1048-54; article available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1266596/ [2] I.M. Rabinowitch, A.F. Fowler, A.C. Corcoran, “Further Observations on the Use of Protamine Zinc Insulin in Diabetes Mellitus,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 36 (Feb. 1937): 111-29; article available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1561995/ [3] Wilfred G. Bigelow, Mysterious Heparin: The Key to Open Heart Surgery (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1990) [4] Best, C.H., “Heparin and Thrombosis: Harvey Lecture, November 28, 1940,” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 17 (Oct. 1941): 796-817; article available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1933740/