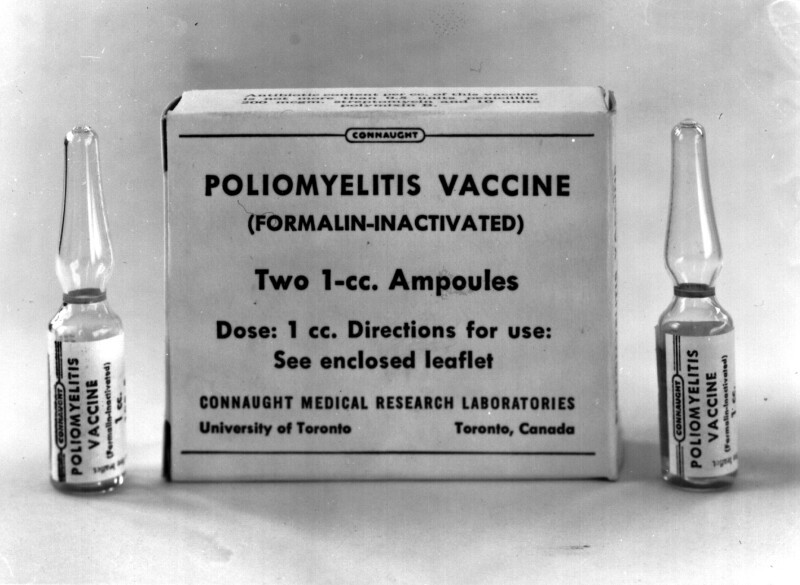

The persistence of the poliomyelitis problem in Canada and around the globe, despite the effectiveness of the Salk vaccine, drove further polio vaccine research and innovation efforts at Connaught Laboratories during the late 1950s and early 1960s. And while the Labs exported some products by this time, particularly insulin and heparin, Connaught’s primary focus was on meeting Canadian needs in public health products. As global demand for the vaccine grew, Connaught’s vital leadership role in developing and producing Salk vaccine, as discussed in Article #7 in this series, presented new export opportunities, particularly as the Cold War intensified. Connaught’s researchers sought to improve the Salk vaccine, and to marry it to existing combined vaccine products. They would also play a major role in the development and global supply of a second type of polio vaccine, a live oral type, pioneered by Dr. Albert Sabin.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[University of Toronto Graduate, Spring 1962]

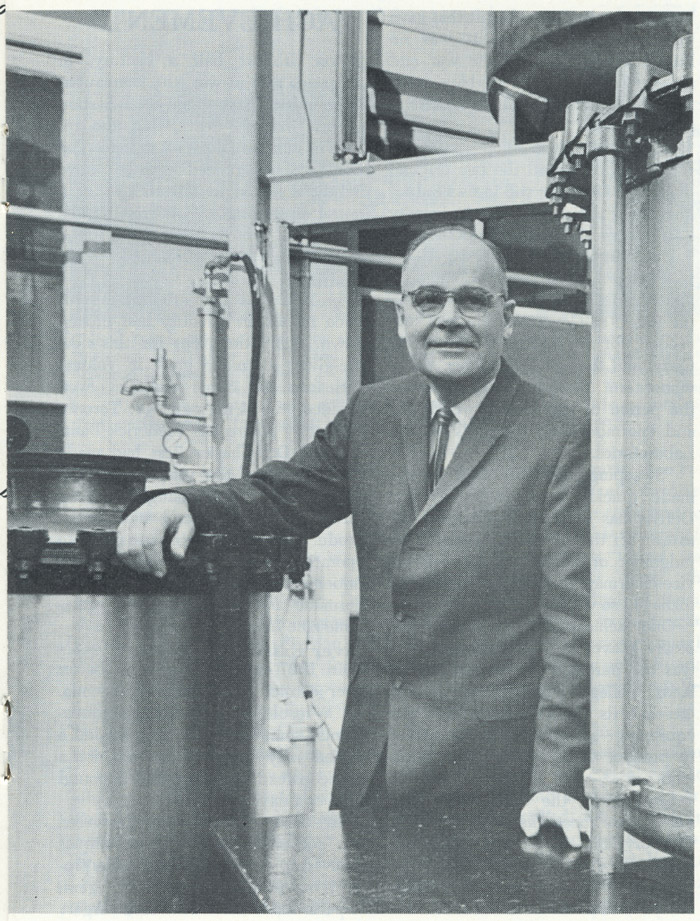

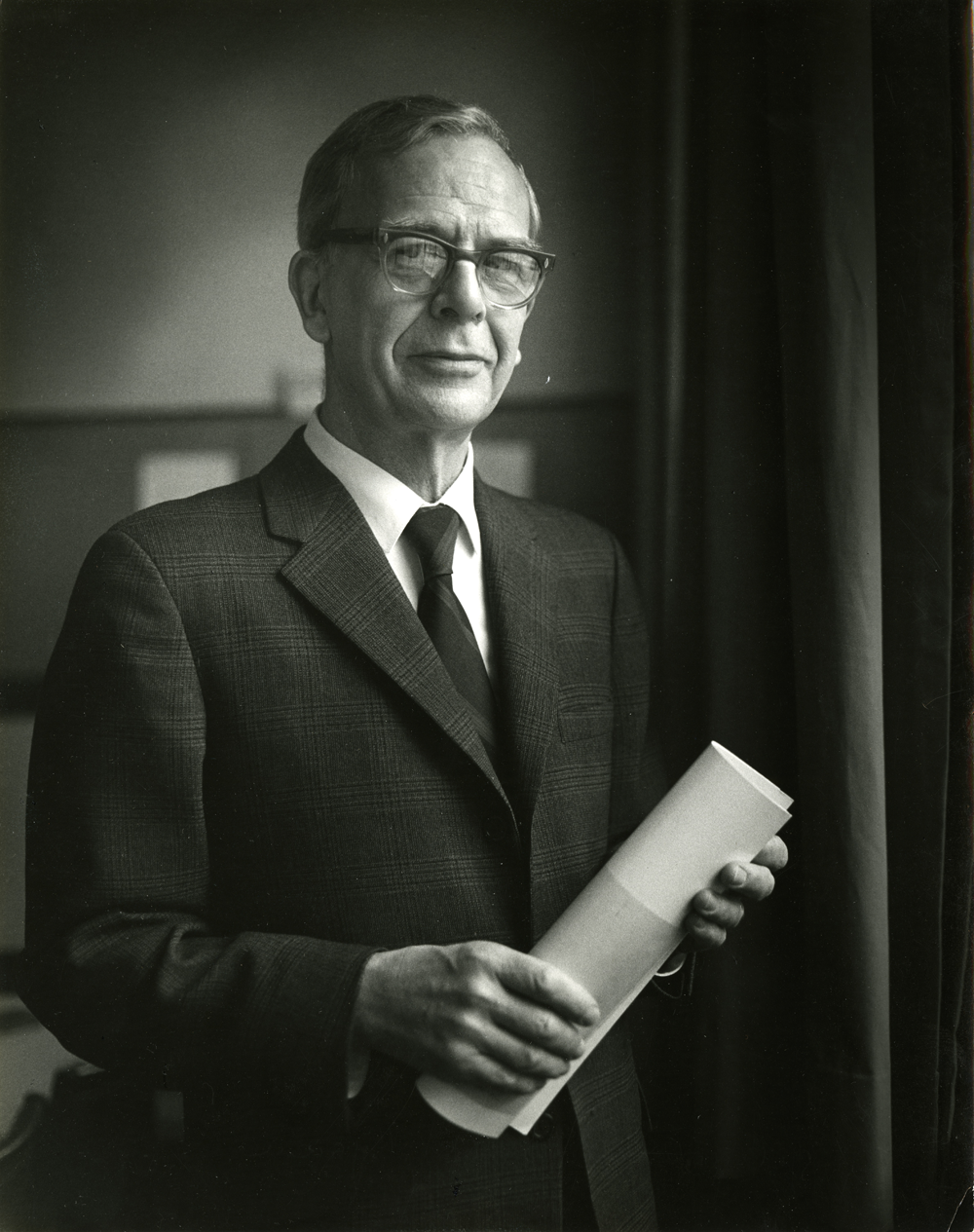

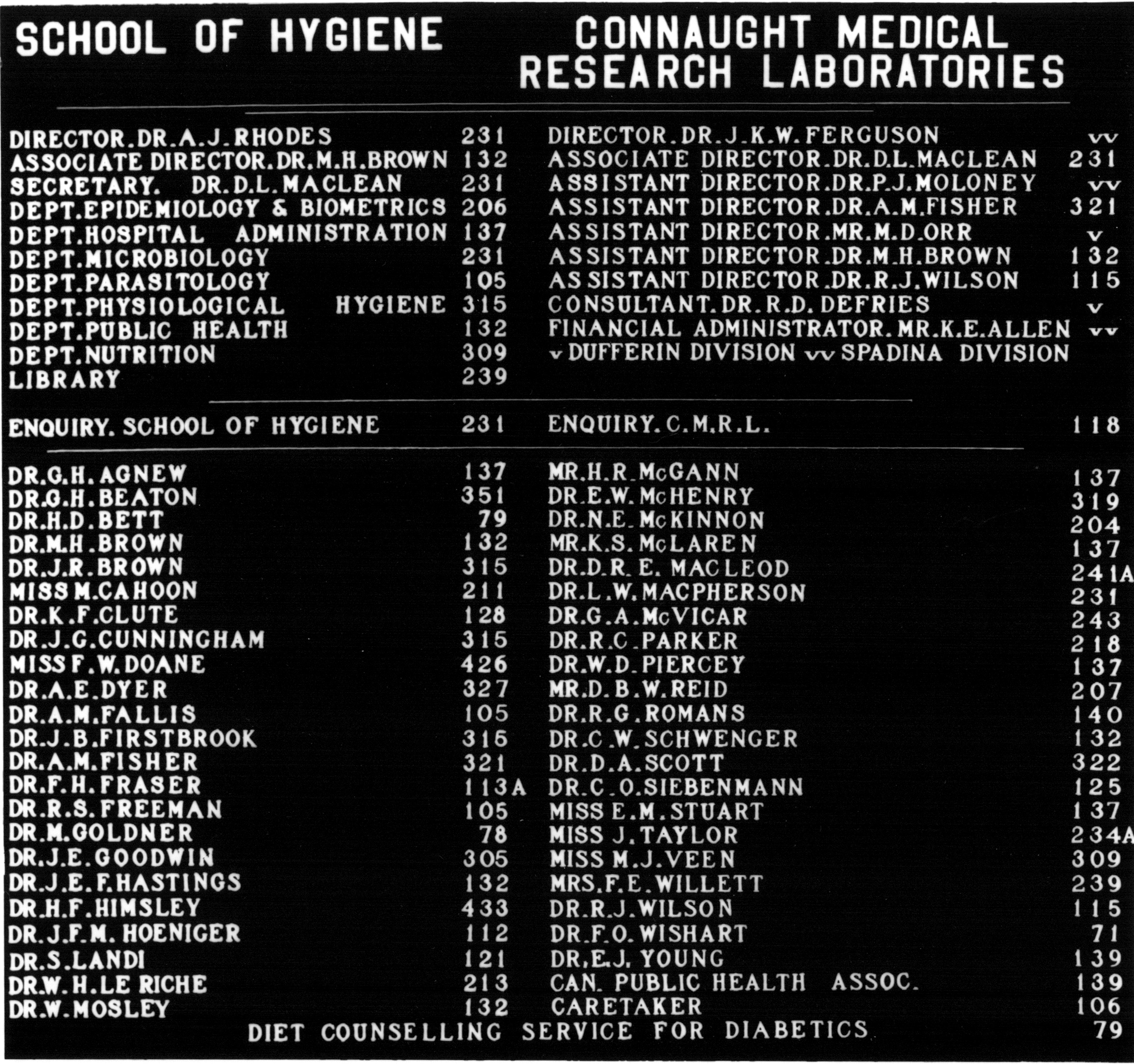

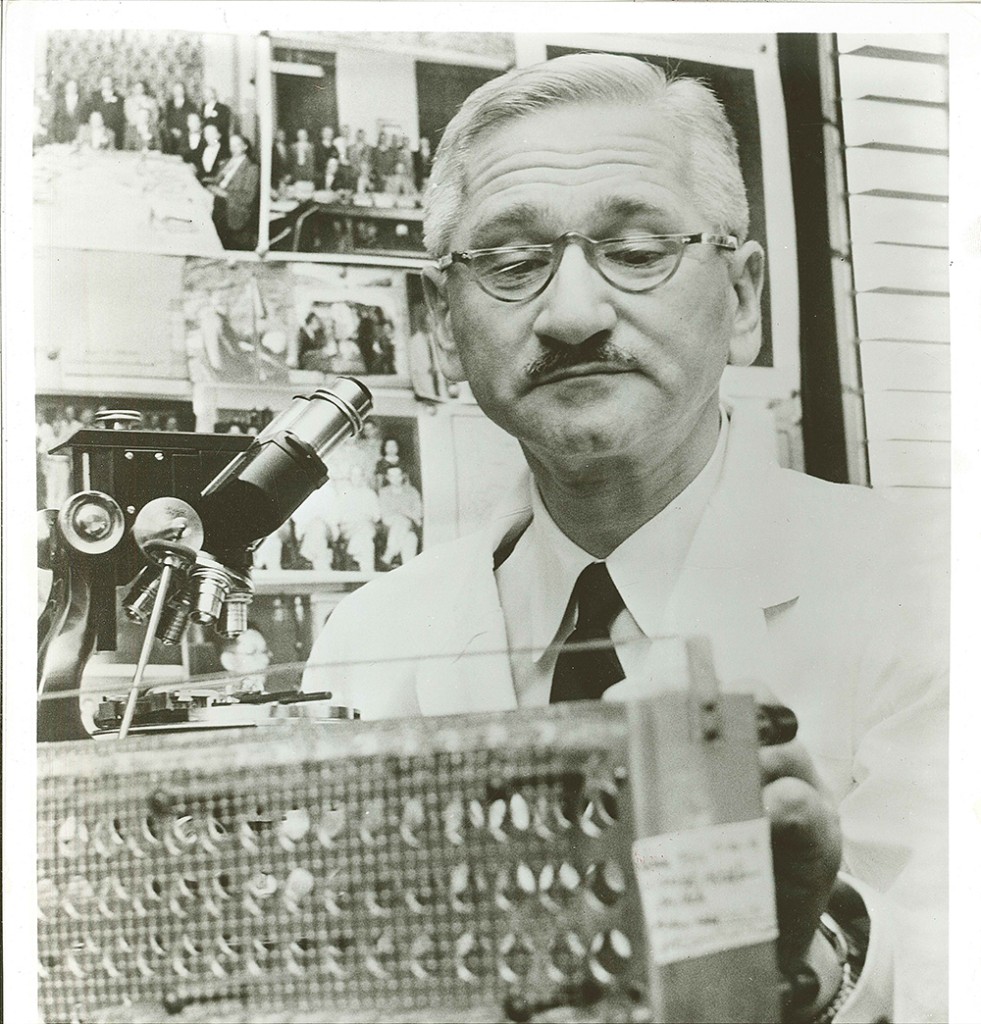

Responsibility for managing Connaught’s post-Salk vaccine launch work, among many other challenges, fell to the Labs’ third Director, Dr. James Kenneth Wallace Ferguson (1907-1999), who succeeded Dr. Robert D. Defries in October 1955. Ferguson was born in Taiwan, the son of Presbyterian medical missionary, Dr. James Young Ferguson, and attended 13 schools around the world before entering the University of Toronto, earning a B.A. in Biological and Medical Science in 1928, a M.A. in Physiology in 1929, and a M.D. in 1932. Insulin co-discoverer, Charles Best became Ferguson’s mentor after they met in 1928 and provided guidance in his choice to focus on physiology and pharmacology studies. Ferguson undertook further studies at Cambridge University in the U.K. in 1933-34, and then held teaching positions in physiology at the University of Western Ontario and Ohio State before serving as a professor of pharmacology at the University of Toronto from 1938 to 1941. While at U of T, Ferguson discovered the utero-pituitary reflex that controls childbirth, also known as the “Ferguson Reflex.” While serving in the R.C.A.F Aviation Medicine Branch during World War Two, he also developed the non-freezing oxygen mask used by air force pilots during the war, continuing research begun by Frederick Banting shortly before his tragic death in a plane crash in 1941. And in 1953, Ferguson led the development of a drug for the treatment of alcoholism known as Temposil. His appointment as Connaught’s Director followed a decade of service, from 1945 to 1955, as the Head of Pharmacology at U of T.[1] When Defries announced his retirement, it was clear that no single person could replace him as director of both Connaught Laboratories and the School of Hygiene. The University of Toronto thus took the opportunity to split the duties of each position. The choice to fill the position of Connaught’s Director came down to Ferguson and Andrew Rhodes, who, as discussed in Article #7, had led the Labs’ poliovirus research work from 1947 to 1953. Rhodes had subsequently become Director of Research at the Hospital for Sick Children and declined the Connaught offer. However, soon after Ferguson began at Connaught, Rhodes was appointed Director of the School of Hygiene, a position he held until 1970. Connaught’s administrative split from the School also prompted the move of its main offices to the Spadina Division, although much of the Labs’ research and production facilities, especially the insulin plant, remained in the Hygiene Building.

[University of Toronto Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

Upon assuming the directorship on October 1, 1955, Ferguson’s main challenge was to stabilize and expand the production of Salk polio vaccine. New testing standards had been implemented following the troubled introduction of the vaccine in the U.S in April 1955 (see Article #7), and Ferguson found himself responding not only to numerous production challenges, including inconsistent inactivation, virus fluid contamination and staff shortages, but also to various critics of the vaccine, anxious about its ultimate safety. Canada’s uninterrupted use of the vaccine drew intense U.S. and international media attention to Connaught, with the Labs finding itself a victim of its success, with any hint of trouble seized upon by some still uncertain about the vaccine. Ferguson readily admitted to the problems Connaught was working through, but was disappointed in many of the press reports, calling them “badly distorted.”[2] Despite the challenges and the critics, Connaught enjoyed the most success with the introduction of the Salk vaccine. There were efforts in several countries outside of North America to prepare the vaccine during 1954-55, including in Denmark, France, South Africa, West Germany, Great Britain and Sweden. But beyond some small-scale production, none of these initiatives were successful; the “Cutter Incident” in the U.S. was blamed for their discontinuation in most cases. However, Connaught’s success with the vaccine attracted the attention of the Soviet Union, which had yet to prepare a vaccine. Thus, in March 1956, a Soviet delegation visited Connaught to inspect the Labs’ polio vaccine production facility and to receive some instruction.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

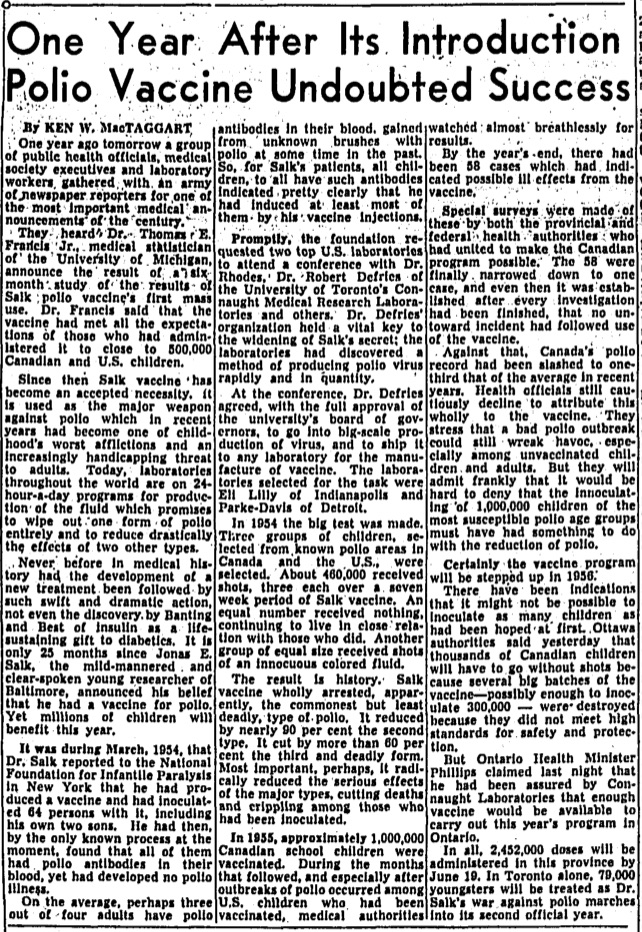

[Globe & Mail, April 11, 1956, p. 17]

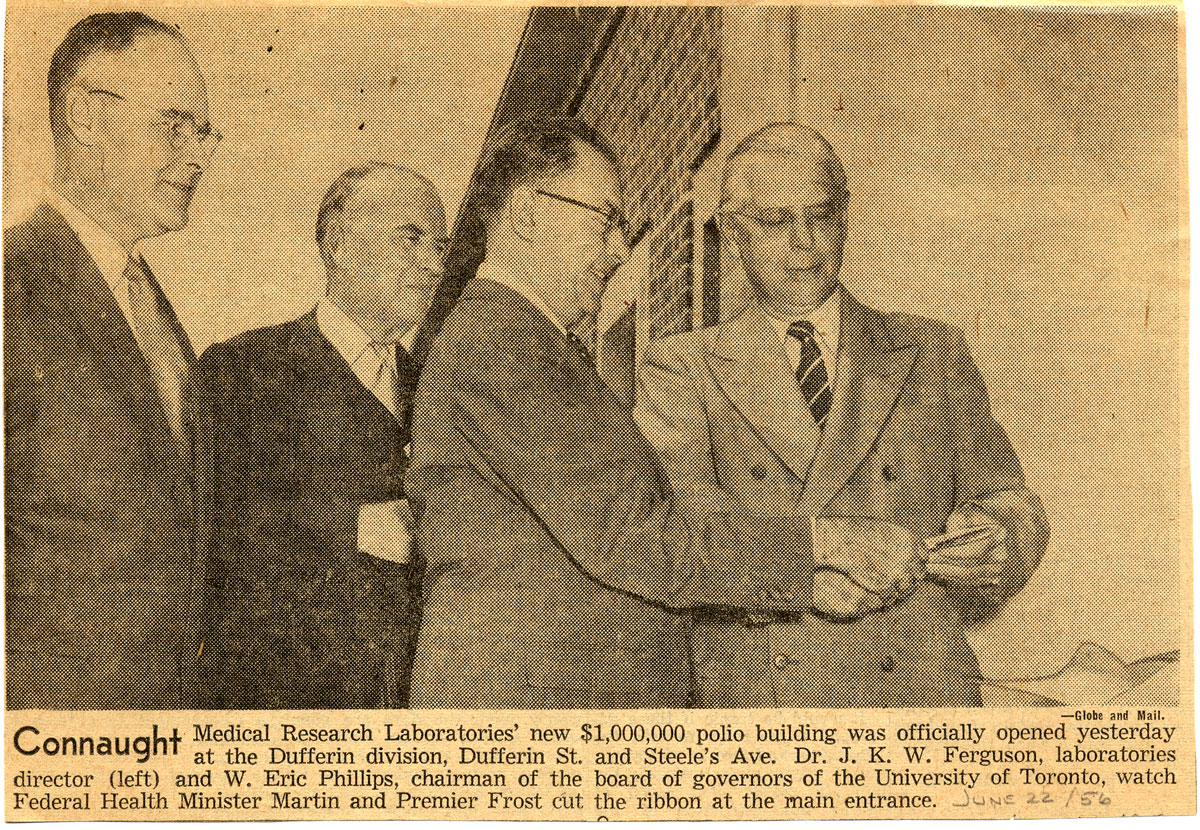

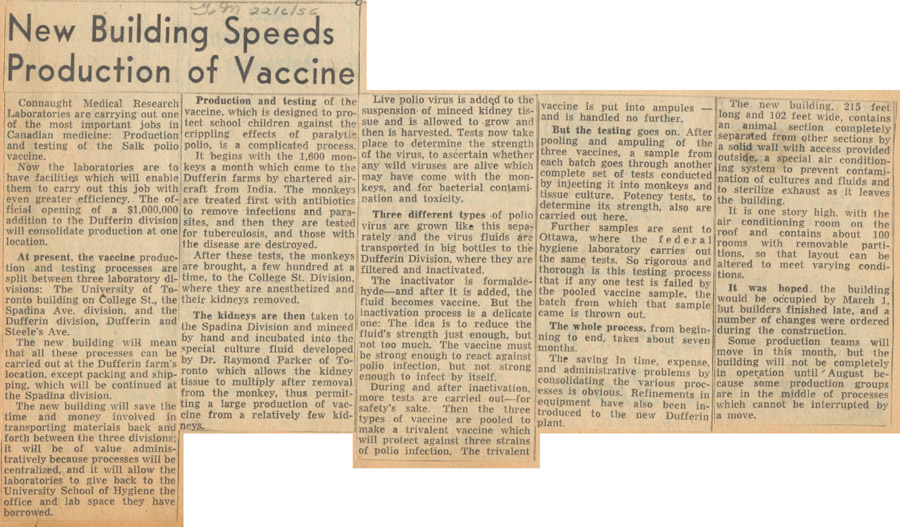

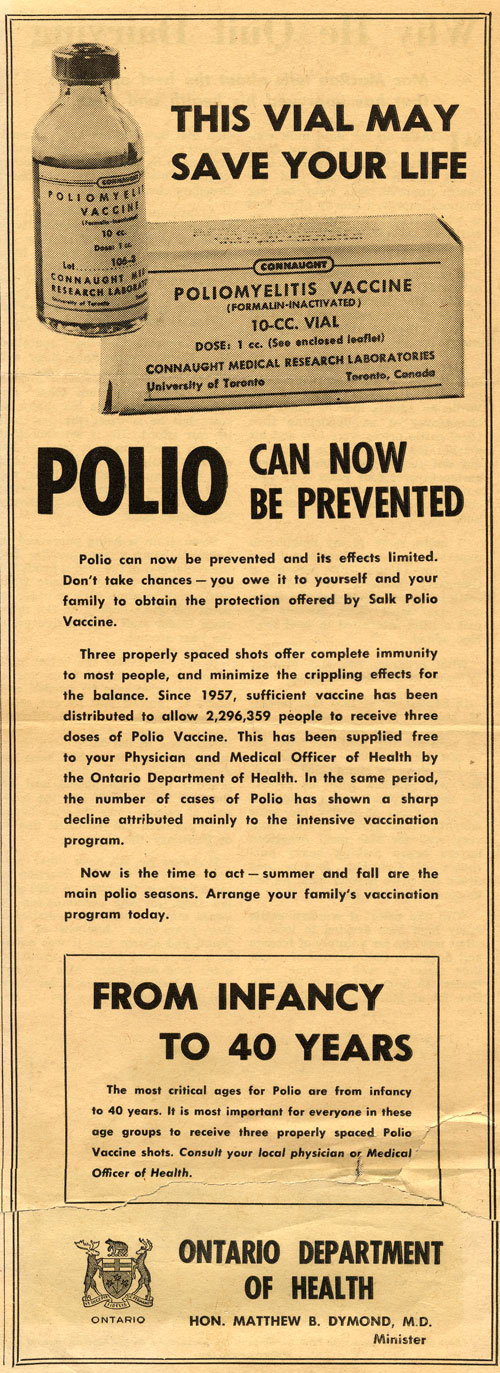

By mid-1956, Connaught had delivered 2.3 million doses of polio vaccine, enough to immunize 1,800,000 children in Canada younger that 10-years-of-age, 90% of whom received at least two doses before the 1956 summer “polio season” began. Three doses were recommended for full protection, but with a limited supply, the priority was to ensure at least some protection for as many of the most vulnerable population as possible. Also by this time, vaccine production had stabilized in the U.S. and there was greater medical and public health confidence in the vaccine. Connaught’s polio vaccine production capacity solidified and expanded significantly as the year progressed, facilitated by the formal opening of a new Polio Building at the Labs’ Dufferin Division on June 22, 1956. By early 1957, Connaught had built up a surplus supply of vaccine, amounting to some 1.3 million doses, which Ferguson hoped could be made available for export, but this would not be a simple matter. There was pressure on the federal government to allow imports of vaccine from U.S. commercial producers, while physicians also pressed provincial governments to add the polio vaccine to its normal list of biological products they provided for free, but which they could charge a fee to administer. However, if the provinces normalized the polio vaccine, they would loose the 50% funding the federal government was providing to ensure its maximum availability through public health clinics, including to older age groups. Thus, a system of public federal/provincial control of the Salk vaccine prevailed in Canada into 1957, which required a reserve be kept of Connaught’s vaccine, but allowed a limited supply from imported commercial sources for those outside the priority age group willing to pay for it. Also, the federal government’s Laboratory of Hygiene maintained a strict policy of testing and approving every batch of polio vaccine and was not equipped to also handle every batch of imported vaccine.

[Globe & Mail, June 23, 1956]

[Globe & Mail, June 22, 1956, p. 3]

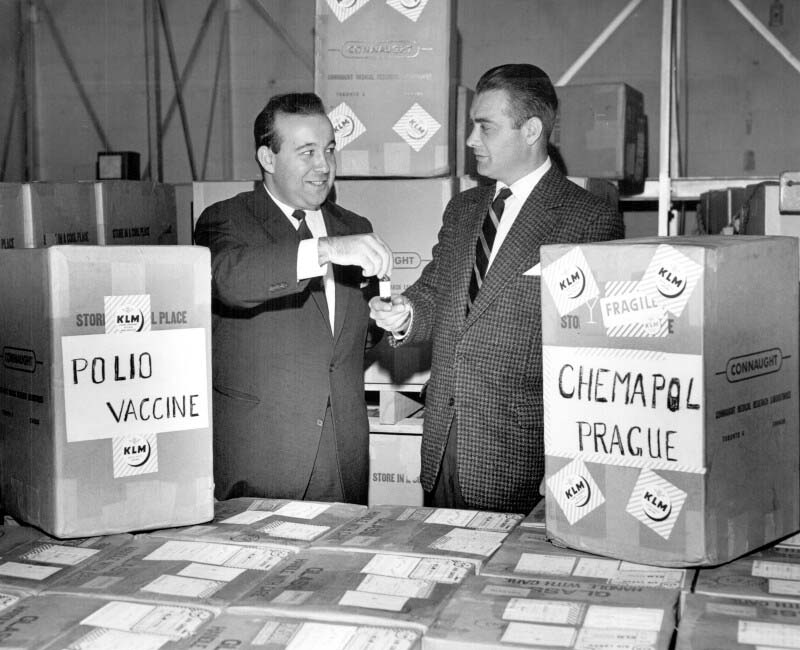

By this time an additional Canadian supply of vaccine, particularly for Quebec, was available from the Institut de microbiologie et d'hygiène at the Université de Montréal. The Institute was established in 1938, along similar public service lines as Connaught and the Pasteur Institute, focused largely on BCG tuberculosis vaccine research and the production of several pediatric vaccines, largely for Quebec distribution. The Institut initiated polio vaccine work in 1954 and the federal and Quebec governments co-funded a new polio vaccine building, which opened in April 1956, although the first vaccine was not available until late 1956.[3] A ban on Canadian vaccine exports was therefore maintained until Connaught’s surplus grew at the same time as U.S. producers began to respond to export demand. It soon became apparent that Connaught’s vaccine surplus had a limited shelf life and that exporting the vaccine would also enhance foreign relations, particularly with Commonwealth countries without their own production capacity. Thus, in April 1957, the export ban was formally lifted and Connaught’s polio vaccine quickly became a “Canadian prestige item,” as T.O. Hecht, of Continental Pharma, Limited, which distributed Connaught’s vaccine, highlighted to Dr. G.D.W. Cameron, Deputy Minister of National Health.[4] By June 1958, over 5.5 million doses of Connaught’s vaccine were shipped to the United Kingdom, while additional vaccine was exported to 44 other countries, including Czechoslovakia; by the end of 1958, Connaught had distributed 17,381,000 doses, double the 1957 total.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

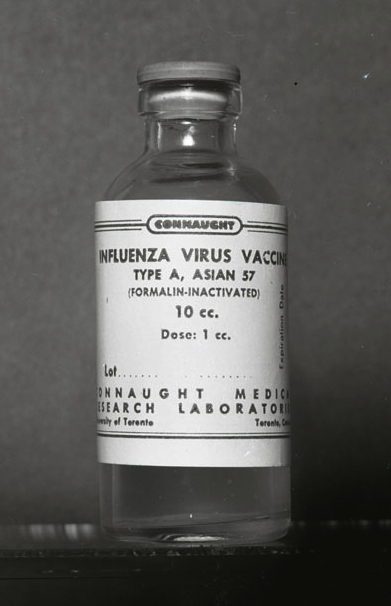

During the summer of 1957, while Connaught had been expanding its polio vaccine supply, routine activities were disrupted when Ferguson received a phone call from the Department of National Health and Welfare on behalf of the provincial governments. The Department asked Connaught to expedite the production of influenza vaccine in response to the threat of a new pandemic strain of Asian influenza A (A/Asia/57, or more specifically A/H2N2), the first pandemic influenza threat since 1918. Emerging in China in late 1956, the new flu strain spread from Asia to Europe and North America, prompting urgent influenza production efforts by labs in Australia and England, as well as six large U.S. pharmaceutical firms. The initial expectation was that the U.S. firms would also meet Canadian demand, but it was soon clear they would not be able to do so and Connaught was thus called on to supply 500,000 doses of vaccine, although the Labs did not normally produce influenza vaccine. The Institut de microbiologie et d'hygiène at the Université de Montréal was also asked to prepare vaccine to help meet this 500,000 dose target. The limited supply that could be produced would only be for use on a priority basis, especially to protect armed forces and health services personnel. Limiting the supply was the availability of hen’s eggs in which the influenza virus was cultivated, and the time it took to produce and test the finished vaccine. To meet this demand, a team within Connaught’s Veterinary Section, which had been established in 1952 to develop and prepare biological health products, particularly for livestock, began cultivating the A/Asia/57 influenza virus in large numbers of fertile hen’s eggs. Connaught was soon able to produce about 10,000 doses per week and was able to deliver the first vaccine supply to the provinces in early October. But just as the vaccine became available, demand declined as the pandemic threat subsided. Fearful of a second pandemic wave the following year, the Dominion Council of Health, which advised the Department of National Health and Welfare, asked Connaught to prepare a further 1 million doses. Fortunately, a second wave did not emerge and the vaccine was not required.

[Globe & Mail, Aug. 17, 1957, p. 1]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

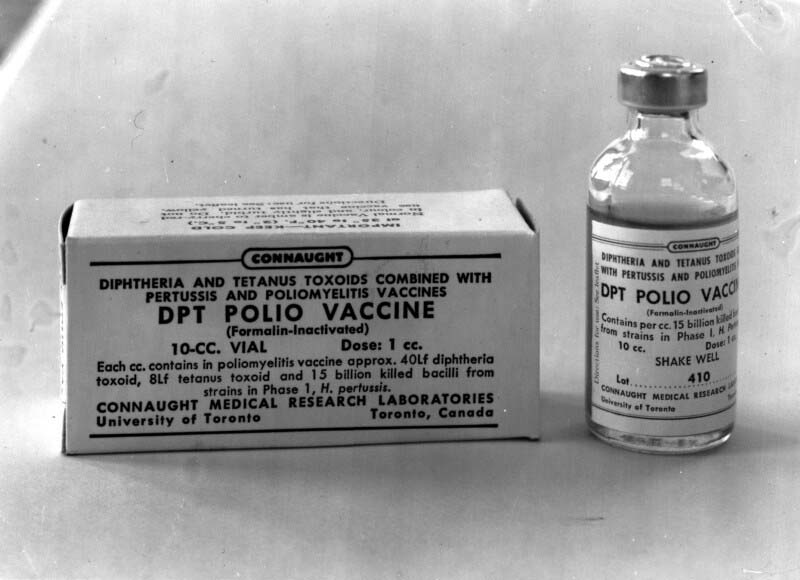

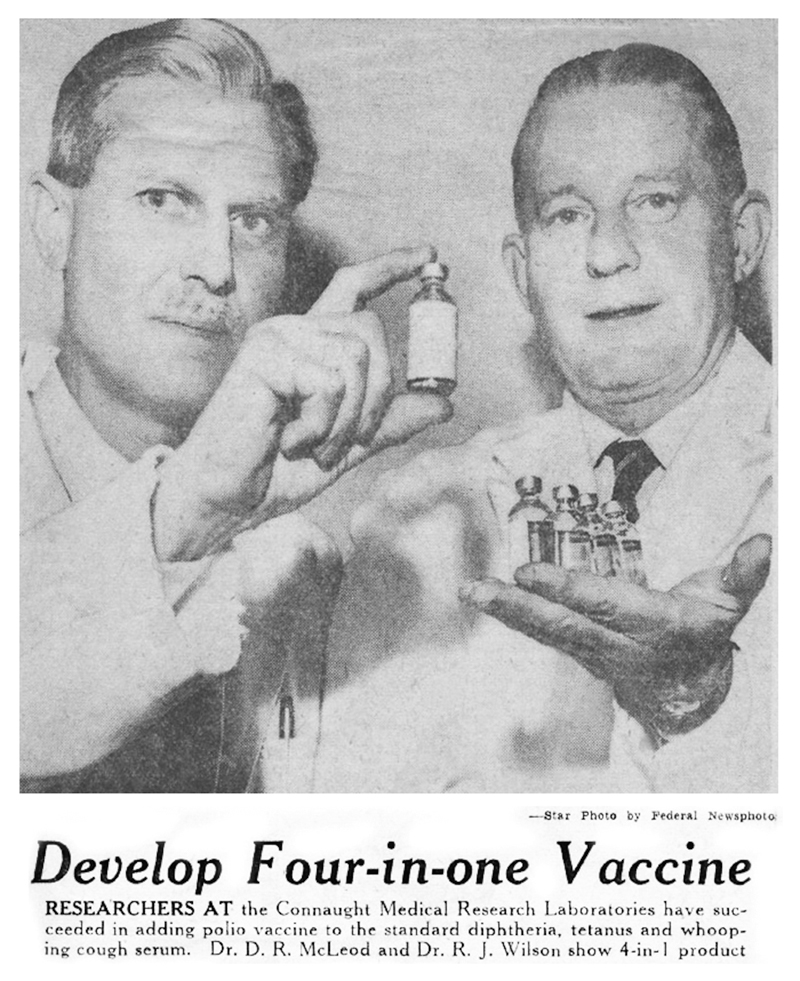

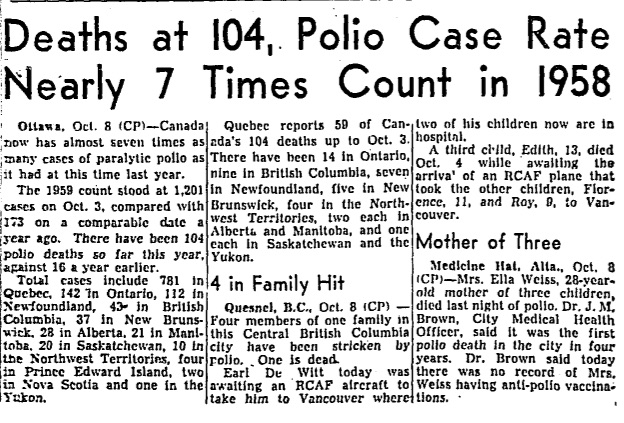

What did occur rather unexpectedly in 1958 was another wave of significant polio outbreaks in several parts of the country. As the initial vaccinations had been provided primarily to the most vulnerable population segment, children aged 5 to 8, the age groups most affected in these outbreaks were instead the pre-school children and older adults who were not yet immunized, or only partially immunized. Medical and public health personnel also faced challenges in administering the Salk vaccine’s three doses, which required additional visits to physician’s offices or public health clinics above and beyond existing immunization programs. Anticipating this challenge when the Salk vaccine was originally introduced in 1955, Connaught researchers, led by Dr. Robert J. Wilson, began a research program to investigate how to combine the Salk vaccine with its DPT vaccine and related combined antigen products. The complicating factor was how to efficiently combine the inactivated poliovirus vaccine with the carefully balanced mixture of the bacterial pertussis vaccine and diphtheria and tetanus toxoids without diminishing the antigenic potency, effectiveness, and safety of each. Connaught was a world leader in the development of combined vaccines, beginning with diphtheria toxoid-pertussis vaccine (DP) released in 1943, followed by the addition of tetanus toxoid to create DPT for primary immunization of young children in 1948, and DT for booster shots in school children and adolescents. In 1958, clinical trials of a new generation of combination vaccines (DPT-Polio for primary immunization, DT-Polio for booster shots in older children, and T-Polio for adults) were launched. They would prove highly successful, paving the way for large-scale production by the summer of 1958 and licensing in early 1959.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Toronto Star, Dec. 15, 1958, p. 44]

By the summer of 1959, and while the use of the Salk vaccine was becoming more common, its adoption was too slow and uneven to prevent a final frightening wave of polio epidemics, causing 1,886 paralytic cases and 182 deaths in several provinces. Though an estimated 45% of Canadians under 40 had received three or more doses of the vaccine by 1959, more than half the population remained vulnerable. Hardest hit were Quebec and Newfoundland, while New Brunswick, Ontario and Saskatchewan also experienced significant outbreaks. Eleven widely scattered paralytic cases in the eastern Arctic were also reported in the Northwest Territories in February and March, primarily among Inuit adults, echoing the major polio outbreak that had occurred in the Chesterfield Inlet area a decade earlier. (See Article #7)

[Globe & Mail, Oct. 9, 1959, p. 1]

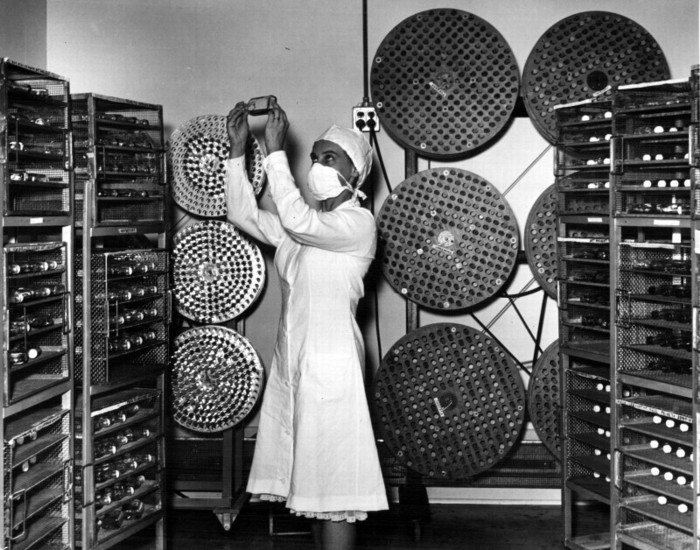

While expanding the production and use of the Salk polio vaccine nationally and internationally, Connaught also intensified its research focus on the development of an oral polio vaccine (OPV), using live, but attenuated or weakened, poliovirus strains developed by Dr. Albert Sabin, a virologist based at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. Salk's vaccine built blood immunity, but Sabin’s polio prevention strategy was based on preparing a vaccine that would build immunity in the digestive tract, where the poliovirus naturally replicates. Sabin’s research was thus focused on carefully selecting and cultivating attenuated poliovirus strains in the laboratory through a complex series of tissue cultures which utilized various animal cells, mostly monkey kidney and testicular tissues, in which the virus replicated.[5] But Sabin’s poliovirus strains remained alive, yet weakened and genetically stable to the point that they consistently stimulated immunity without causing disease. The finished vaccine would be easily administered with a spoon, or dropped onto a sugar cube. Once Sabin provided seed samples of his attenuated poliovirus strains, the OPV production process was not as technologically complex as for Salk’s vaccine. They involved more precise and painstaking work with tissue culturing, requiring highly sterile conditions and constant testing of the genetic stability of the attenuated strains. OPV’s advantages include ease of administration, lower cost, longer immunity, and the ability of the vaccine strains to spread in a community and immunize beyond those directly given the vaccine, thus potentially stopping outbreaks. This latter advantage also carried the very low, but real, risk of live vaccine strains reverting to virulence and directly or indirectly causing polio.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Public Domain Image]

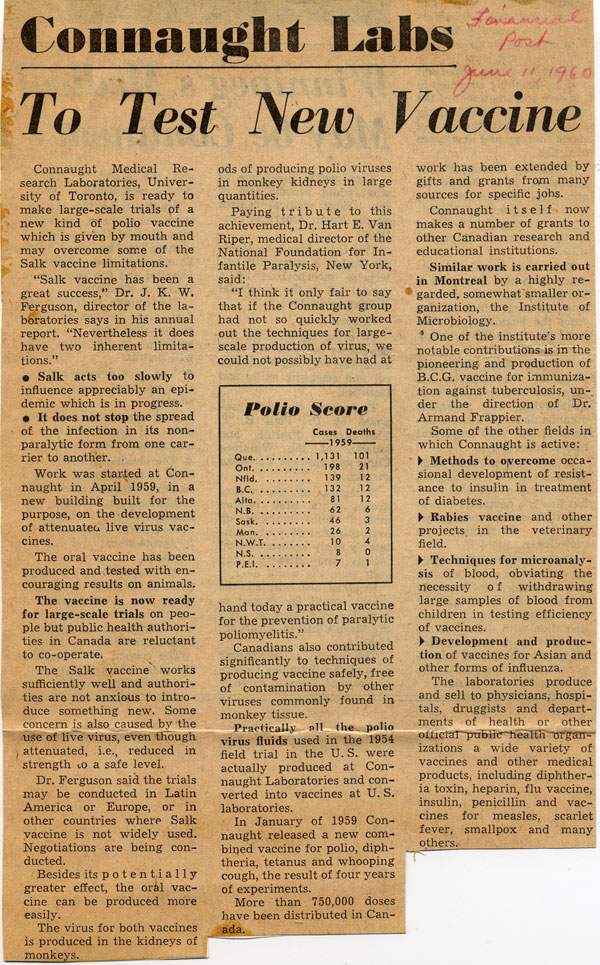

Connaught’s initial research work on a live polio vaccine began in 1956, but development accelerated in July 1959 when Sabin provided the Labs with a “seed pool” of his attenuated strains that represented the three distinct antigenic types of the poliovirus. As Connaught did with the Salk vaccine, and continuing its interest in preparing multiple antigen products to simplify vaccine administration, the Labs focused on producing a single trivalent OPV product. Other manufacturers, particularly in the U.S., prepared separate monovalent vaccines for each poliovirus type. After refining its OPV production methods and the precision of the testing required, Connaught then played an important role in facilitating its evaluation by participating in a well-coordinated series of field “demonstrations” of the vaccine in several provinces during 1960-61. These OPV “demonstrations” were conducted under the supervision of a National Technical Advisory Committee on Live Poliomyelitis Vaccines, established in October 1959 by the Department of National Health and Welfare, and supervised by Dr. Andrew J. Rhodes. Since the Salk vaccine was already in wide use, a large-scale placebo-controlled field trial—like the one it had received—was not possible with OPV. Evaluations of the vaccine were focused on a series of genetic stability studies of attenuated polioviruses conducted in Quebec City and Montreal, followed by larger community focused field demonstrations in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, and in two rural communities in Nova Scotia. Based primarily on these Canadian demonstrations, Connaught’s OPV was licensed for use in Canada in March 1962.[6] OPV would soon supplant the Salk vaccine in some provinces, while in others, particularly in Ontario and Nova Scotia, the Salk vaccine in the DPT-Polio combination was still preferred. While OPV was under development at Connaught and by other producers in the U.S. and other countries, particularly the Soviet Union, and prior to OPV’s licensing in Canada and the U.S., the international politics surrounding its evaluation and supply grew complex. In a context of high polio incidence, several countries hosted large-scale OPV field trials based on rival vaccine strains, of which there were several, although Sabin’s seemed the safest. In 1959, and deep in the Cold War period, Sabin’s vaccine attracted the most attention when the Soviet Union boldly vaccinated its entire population based on vaccine seed pool strains Sabin had provided, and then offered to give it away to any country willing to accept it.

[Financial Post, June 11, 1960]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

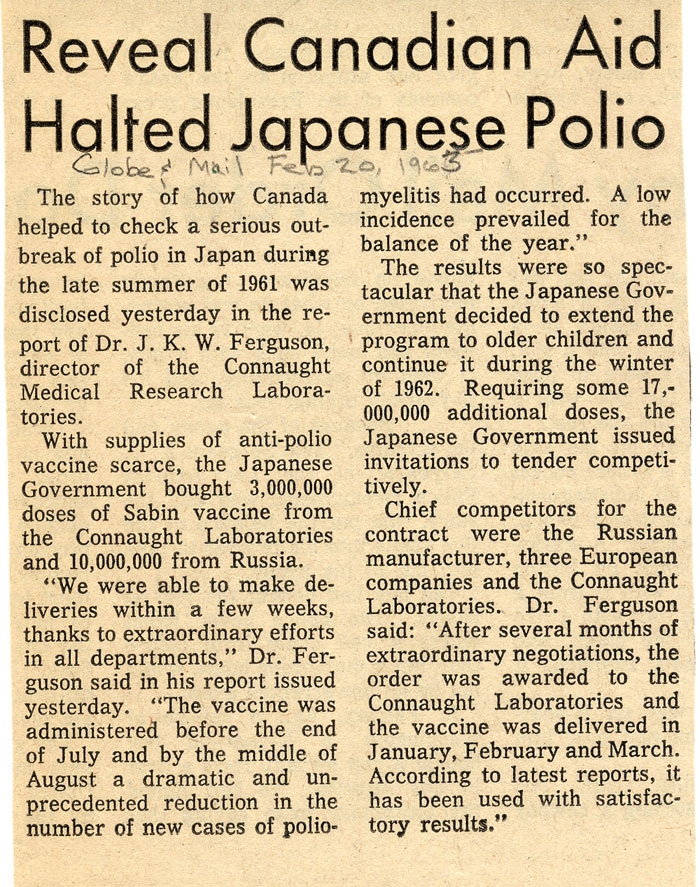

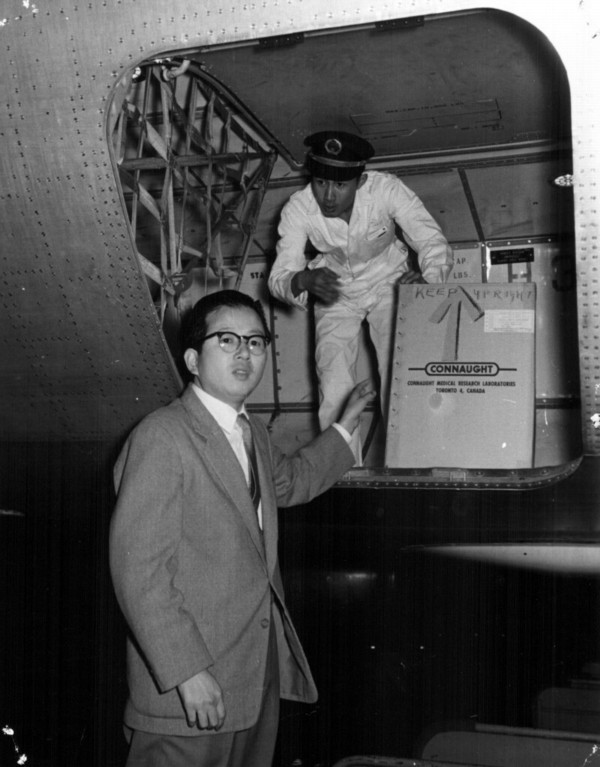

This situation was further politicized since no American vaccine could be exported without a federal license: it had to first meet domestic standards. In Canada, an export license for the vaccine was not required at the time, and Connaught had only to satisfy the requirements of the importing country. This provided Connaught with an advantage over American OPV producers. Connaught was freer to export its still unlicensed vaccine to countries desperate for any kind of protection from epidemic polio. For example, in 1961, Connaught expedited sending 3 million doses of OPV to Japan to help bring a major polio epidemic under control. This episode led to a further order by the Japanese government for 17 million doses of Connaught’s OPV. While paralytic polio as an epidemic threat in Canada essentially ended in 1962, the same was certainly not true in most other countries, particularly in the developing world. Indeed, despite the availability of two effective polio vaccines, annual global polio incidence remained as high as 350,000 cases until the launch of the World Health Organization’s polio eradication initiative in 1988. Meeting the global challenge of polio prevention would remain a major focus of activity at Connaught. In mid-August 1962, not long after Connaught’s OPV was licensed in Canada, 14-year-old Jimmie Orr arrived on a train in Toronto not feeling well and with the first characteristic pock marks of smallpox emerging on his face. He had been feeling unwell during a flight from Brazil to New York City with his parents. After clearing customs and a medical check, he boarded a train to Toronto. On August 17, Jimmie’s condition worsened and smallpox was finally confirmed three days later. His diagnosis sparked an international effort to track down and vaccinate all of Jimmie’s possible contacts in a desperate effort to prevent a potential smallpox epidemic. Prior to Jimmie’s relatively mild case, the last smallpox cases in Canada and the U.S. were seen in the 1940s, although the disease remained a major threat in the developing world. Jimmie’s case sharply revealed a disturbing vulnerability to the disease, particularly in North America and Europe, exacerbated by increasing international travel, and sparked a global initiative to eradicate smallpox. As will be discussed in the next article of this series, Connaught would play a key role in making the eradication of smallpox possible.

[Globe & Mail, Feb. 20, 1963]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Globe & Mail, Aug. 20, 1962, p. 1]

Useful Resources:

Bator, Paul: Within Reach of Everyone: A History of the University of Toronto School of Hygiene and the Connaught Laboratories Limited, Volume 2, 1955-1975; With An Update to the 1990s (Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association, 1995) Defries, Robert D.: “Present Status of Poliomyelitis Vaccination,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 77 (7) (Oct. 1, 1957): 663-70; article available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1824229/ Ferguson, J.K.W.: “Live Poliovirus Vaccine for Oral Use,” Canadian Journal of Public Health, 53 (April 1962): 135-42. Rutty, Christopher J: “’Do Something! Do Anything!’ Poliomyelitis in Canada, 1927-1962, Ph.D. Thesis, Department of History, University of Toronto, 1995; available here: http://healthheritageresearch.com/clients/docs/Polio-PHD/Rutty-CJ-PolioInCanada-PhDThesis-UT-History-1995-digitalversion.pdf Rutty, Christopher J.: “Dr. Robert D. Defries (1889-1975): Canada’s ‘Mr. Public Health’”, in Lois N. Magner (ed.), Doctors, Nurses and Practitioners (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1997: 62-69; available here: http://healthheritageresearch.com/Defries-biopaper.html Rutty, Christopher J.: “Conquering the Crippler: Canada and the Eradication of Polio,” Canadian Journal of Public Health 96 (March-April 2005): special insert; available here: http://healthheritageresearch.com/ConqueringtheCrippler_e.pdf Rutty, Christopher J. and Sullivan, Susan: This is Public Health: A Canadian History (Canadian Public Health Association, 2010), online eBook: https://www.cpha.ca/history-e-book Sanofi Pasteur Canada, “The Legacy Project”: http://thelegacyproject.ca “Vaccines & Immunization: Epidemics, Prevention & Canadian Innovation: The Online Exhibit, Museum of Health Care, Kingston (2013-14); http://www.museumofhealthcare.ca/explore/exhibits/vaccinations/ Wilson, R.J.: “Canada’s Experience With Multiple Antigens,” Canadian Journal of Public Health, 53 (Nov.. 1962): 457-62. “Within Reach of Everyone: The Birth, Maturity & Renewal of Public Health at the University of Toronto,” Dalla Lana School of Public Health website feature: http://www.dlsph.utoronto.ca/history/

Endnotes:

[1] Obituary, James Kenneth Wallace Ferguson, Canadian Medical Association Journal, 162 (April 18, 2000): 1259; available at: http://www.cmaj.ca/content/162/8/1259; J.K.W. Ferguson, Biographical File, Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives. [2] J.K.W. Ferguson to H.K. Faber, Dept. of Pediatrics, Stanford University, Nov. 4, 1955, Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives, 83-003-03. [3] Pierrick Malissard, “Les ‘Start-Up’ de jadis : La production de vaccins au Canada. Sociologie et sociétés, 32(1) (2000): 93–106; article available at: https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/socsoc/2000-v32-n1-socsoc74/001159ar/; “Laboratoire de la Poliomyelite, Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene, Division of Laval-des-Rapides, University of Montreal,” Canadian Journal of Public Health, 47 (July 1956): 318. [4] T.O. Hecht, Continental Pharma Ltd. (CMRL distributors of Salk vaccine) to G.D.W. Cameron, Deputy Minister of National Health, Aug. 14, 1957, Library and Archives Canada, RG29, Acc. 85-86/248, Vol. 34, file 311-P11-33. [5] A.B. Sabin and L.R. Boulger, “History of Sabin Attenuated Poliovirus Oral Live Vaccine Strains,” Journal of Biological Standardization, 1 (1973): 115-18. [6] Editorial, “Oral Poliovirus Vaccine,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 86 (11) (March 17, 1962): 500-01; article available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1848933/