[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

However, amidst the building boom, there was a growing sense of uncertainty surrounding Connaught’s relationship with the University. The consolidation of the Labs’ operations at the Steeles Ave. site, especially since the Labs’ 1955 administrative split from the School of Hygiene (see Article #8), underscored its geographic distance from the main University campus (20 km), as well as a growing academic separation. There was a clear drift in what had been more common scientific and research enterprises and in the opportunities for teaching and the supervision of graduate studies by cross-appointed members of Connaught’s staff. In addition, sharply rising regulatory demands, a growing export business and intensified international competition (see Article #10), created a challenging situation. New production facilities, built to meet higher standards, were urgently needed. Yet, the self-sufficient Labs’ resources were limited and the University was struggling to meet demands brought on by the post-war baby boom generation coming of age. During 1971-72, this sense of uncertainty sharply intensified, especially after the University received a compelling offer to buy Connaught Laboratories and transform it into a profit-oriented company.

Building Booms

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

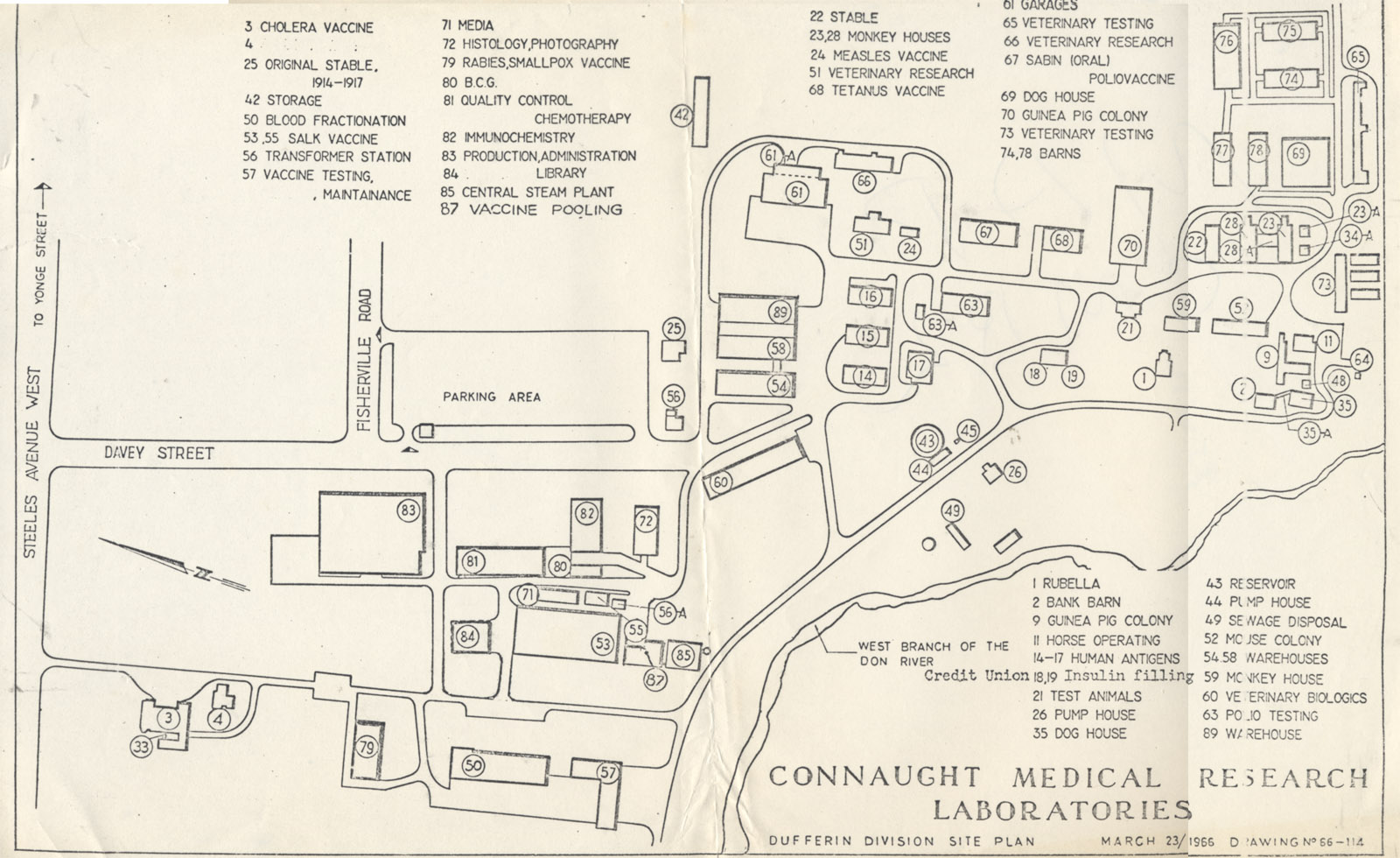

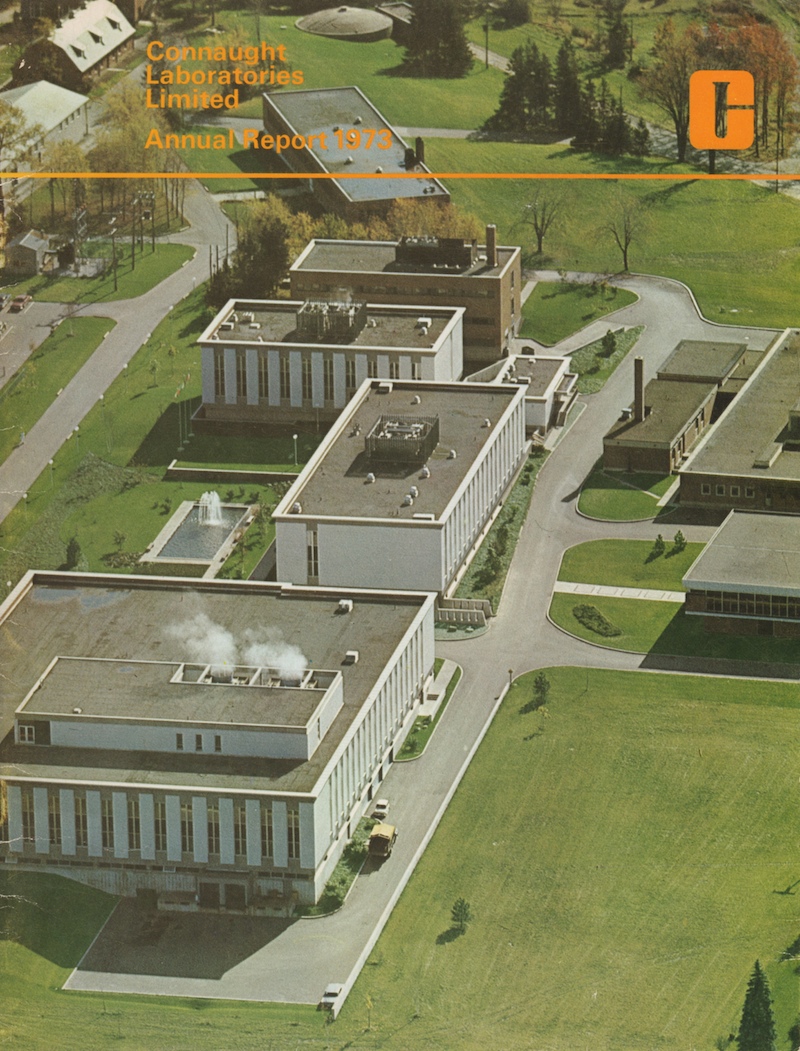

During the early 1960s, Connaught’s Dufferin Division had experienced an initial “building boom,” fuelled primarily by strong growth in domestic and especially export distribution of Salk and Sabin polio vaccines, as well as with bacterial vaccines, insulin and veterinary biologicals. The opening of the Veterinary Biologics Building in 1960 (building #60), which consolidated the Labs disparate veterinary facilities, was followed by the erection of another 18 new buildings during 1960-63. Several buildings were for veterinary product testing and research, animal services and stables, while others were built for Sabin polio vaccine production, the preparation of media, and human vaccine research. The major “building boom” of the 1960s began in early 1966 with the opening of building #79, designed for rabies and smallpox vaccine development and production, especially in support of the global smallpox eradication program (see Article #9). Building #80 also opened in early 1966 for tuberculosis-related BCG vaccine and Tuberculin diagnostic products development and production (see Article #11).

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

In June 1966, Connaught’s future looked quite bright when the FitzGerald, Fraser and Gooderham buildings were formally opened. As was noted in Connaught’s 1965-66 Annual Report, “the three new buildings were designed as a group and display a degree of beauty and dignity worthy of the men they commemorate:” John G. FitzGerald, visionary founder of the Labs; Donald T. Fraser, pioneer of vaccine research and development; and Albert E. Gooderham, who donated the land upon which the Labs had grown.[1] The buildings were arranged around a picturesque pool, fountain and garden and adjacent to a new main entrance on a side street on the east side of the site. The new entrance included a guardhouse to more securely manage traffic, staff and visitors. The entrance now also featured the Barton Avenue Stable, which had originally been moved to the “Farm” site in 1935 to preserve it with the intention of creating a museum; that idea, however, would not be realized until 2004.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

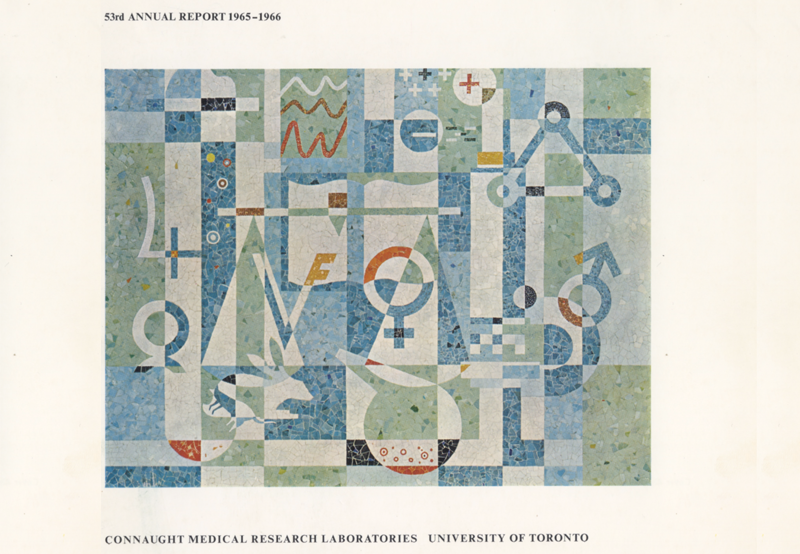

While the presence of the Barton Avenue Stable at the new entrance underscored Connaught’s more than half-century legacy, the Labs’ modern mission was symbolized in a specially commissioned mosaic mural installed above the main entrance to building 83, which led to the site’s reception area. The 20’ x 20’ mosaic was crafted by Alexander von Svoboda (1929-2017), who was among the most prominent artists in the world specializing in large mosaic artworks. Most of Svoboda’s creations involved murals made with "smalti" (a glass tile material), and a classical mosaic technique developed in Italy, which Svoboda mastered and brought to North America. The mosaic’s design, which featured a variety of iconic scientific items and symbols, such as a microscope, a scale, a mouse and a test tube, captured, as Svoboda recalled in an interview with the author, “the progress and research of the Connaught Labs company, and will outlive the next century.”

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

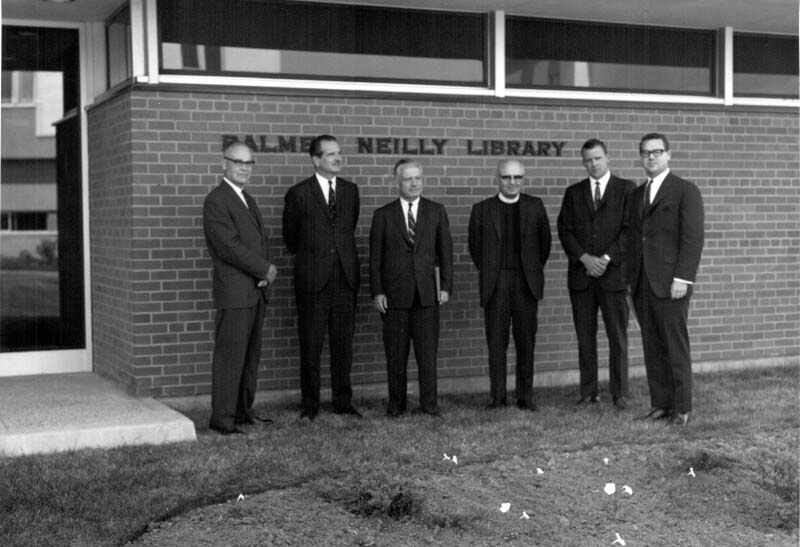

The mid-1960s building boom concluded with the opening of a very different new building, both in its design and function: the Balmer Neilly Library (building 84). Balmer Neilly had served as the Chairman of the Connaught Committee of the University of Toronto’s Board of Governors from 1938 through 1949. In 1963, his widow donated $350,000 to the Labs to be specifically used to build a new library. Connaught’s main library, which had grown out of FitzGerald’s original book and journal collection, was accommodated in the School of Hygiene. In 1958, the library was extended to the Dufferin Division to reside in building 57 until building 84 formally opened on June 27, 1967.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

After the frenetic pace of the 1960-67 period, building construction slowed over the next few years, although the planning of two major new buildings was underway. The most challenging project, especially from financial and regulatory perspectives, was consolidating and upgrading the Labs’ bacterial vaccine facilities for pertussis, diphtheria and tetanus vaccines production. The University of Toronto was unable to help fund the $1.5 million building project as it had for previous buildings, leaving the Labs to finance the project based primarily on earnings from export sales. The Labs also had to meet significantly higher Canadian and U.S. regulatory demands before plans were approved and construction could proceed (see Article #10). The new bacterial vaccines building (#90) was finally opened in June 1973 and later named the Peter J. Moloney Building in honour of Connaught’s pioneering immunochemist.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

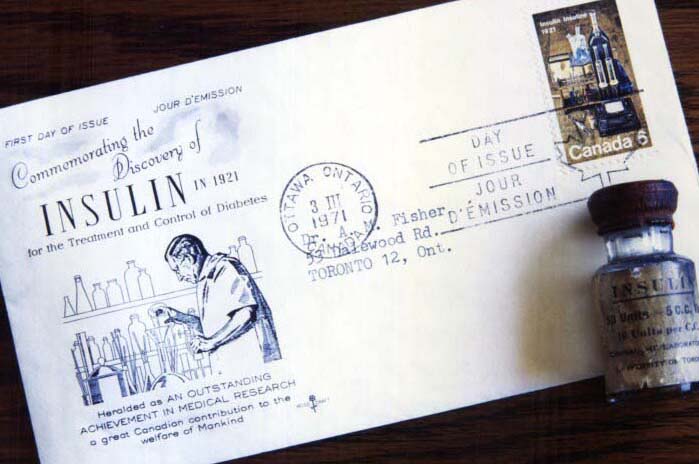

However, the most pressing need was the consolidation of the last elements of Connaught’s insulin operations at the Dufferin Division site. An upgraded and larger insulin extraction facility was required to replace the original insulin plant located in the School of Hygiene building. Plans for a new insulin facility began shortly after the administrative split of Connaught from the School in 1955-56. Starting in the late 1950s, some elements of insulin production moved to the Dufferin site, such as the purification process into insulin crystals, and testing, formulation, and then filling/packaging in building 83. Momentum to consolidate Connaught’s insulin operations increased in 1968 after the Medical Building at the University campus was demolished to make way for a new Health Sciences complex. As discussed in Article #3, insulin had been discovered in the Medical Building, and the Insulin Committee’s Laboratory, responsible for testing of insulin prepared by licensed producers, had occupied the original space in which Connaught had first produced insulin during 1922-23. The Insulin Committee Lab found a new home on the top floor of building 72 at the Dufferin Division. To create a physical connection between the old and the new sites of insulin production, some bricks from the original U of T building were preserved and incorporated into the wall of the front lobby of building 86, along with a display case to showcase historical documents and vials of early insulin. Building 86 was named the Robert D. Defries Building to honor the second Director of Connaught and the School of Hygiene (1940-1955), who played a critical role in establishing the production of insulin on a large scale at Connaught.[2] On November 20, 1970, Defries attended the official opening of the building named in his honour, as did several other dignitaries, including insulin co-discoverer, Charles Best. The opening of the Defries building also launched a series of celebrations surrounding the 50th anniversary of the discovery of insulin, which climaxed with several events in Toronto in October 1971. However, the insulin 50th took place at a critical time for the Labs.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

Future Considerations

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

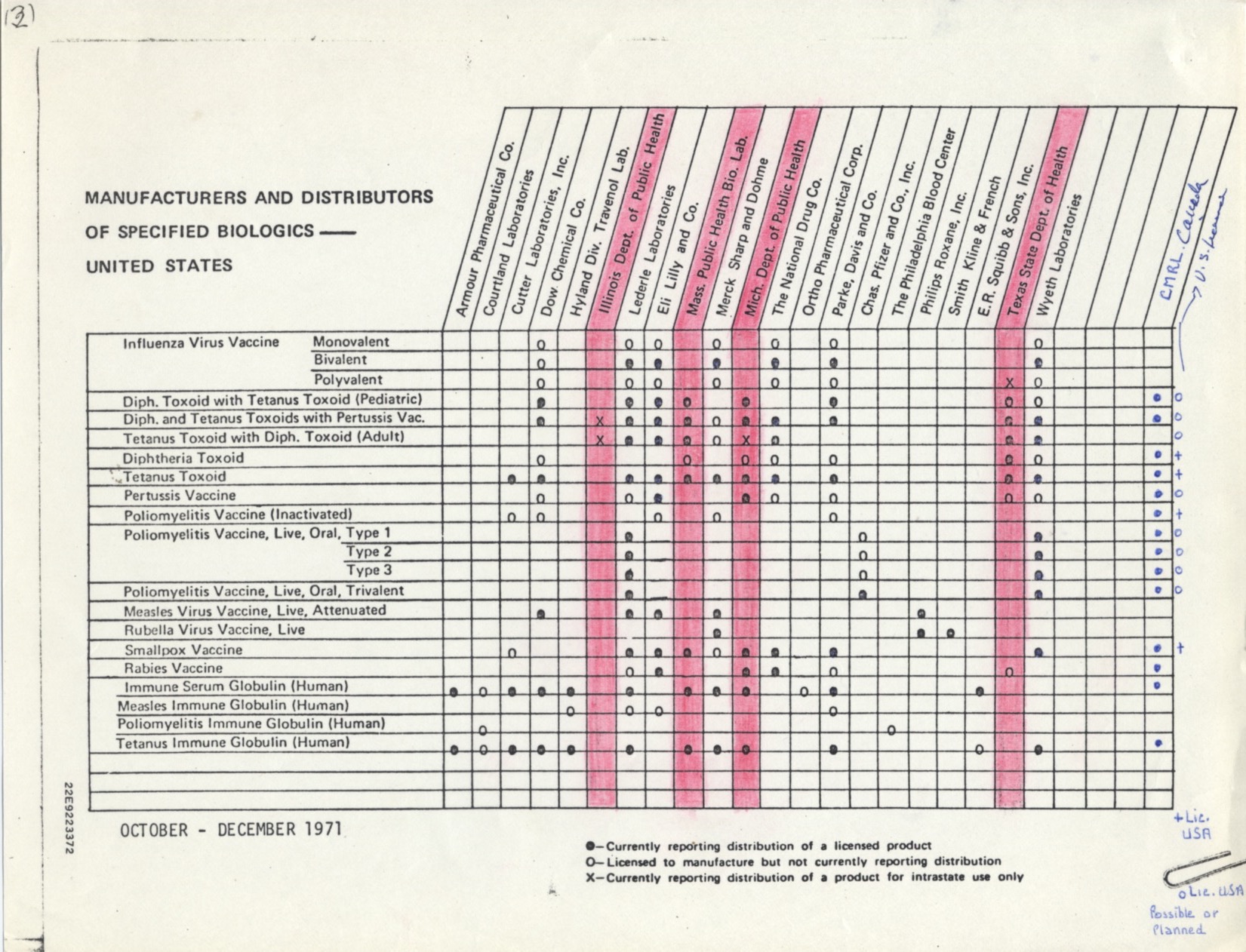

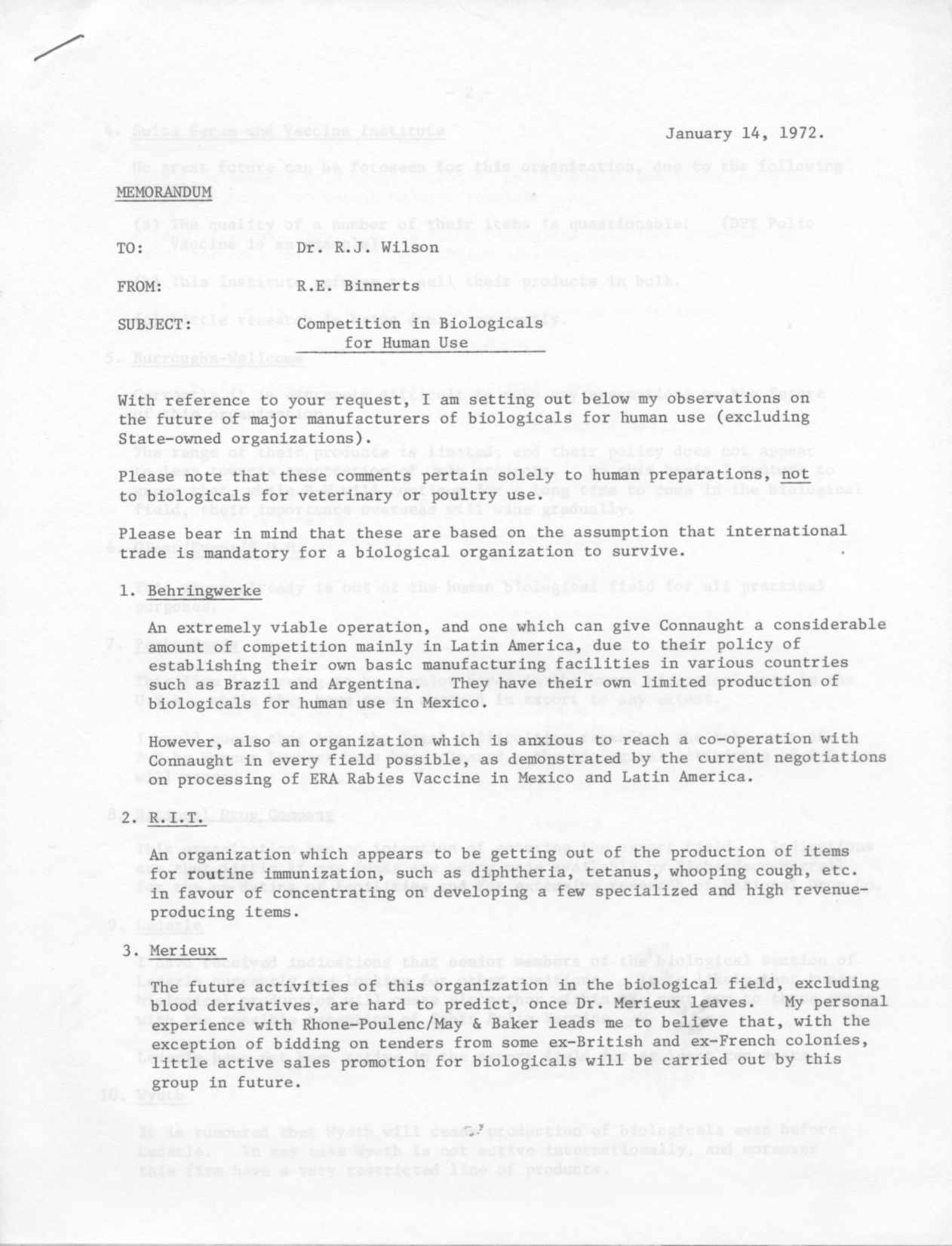

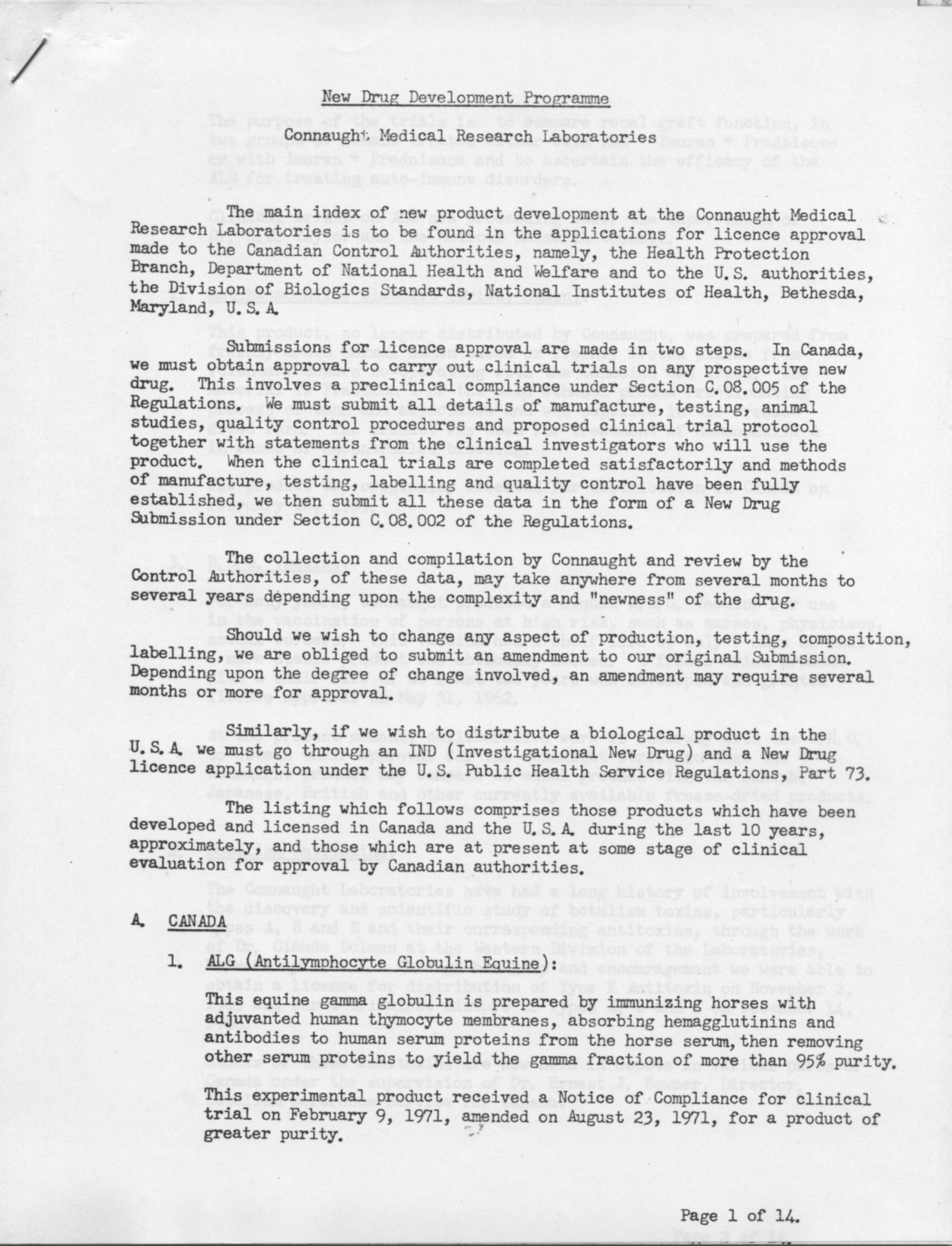

In the global context of vaccine production, as described in a January 14, 1972 internal report detailing “Competition in Biologicals for Human Use,” Connaught was well placed when compared to U.S. and European commercial biologics manufacturers with respect to production, and especially research and development. The report was prepared based on the general assumption that international trade was mandatory for a biologics organization to survive. However, at the time, all but one of the firms described in the report were of “waning” or “decreasing importance,” had limited to no international export activities, would focus on a more limited range of vaccines, or were expected to soon leave the vaccine business entirely.[3] Furthermore, as another internal report, “New Drug Development Program,” prepared in March 1972, also made clear, Connaught remained very active in biologics development. The report focused on the status of applications for license approval that had been made to Canadian and U.S. regulatory authorities. There were a total of 23 distinct products that had active Canadian license applications that were new applications, or were based on substantive production improvements and pending clinical trial results.[4] Thus, while other vaccine producers were waning in their export and research and development activities during the early 1970s, Connaught stood out in both areas.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

During 1971-72, amidst this considerable activity at Connaught, the University of Toronto’s Connaught Committee was considering the Labs’ future. A new University of Toronto Act was being developed by the province that would involve creating a more complex Governing Council to replace the Board of Governors. How would this change in the university’s governance affect the Connaught Committee and Connaught within the university? Such discussions were also prompted by the pending retirement of Dr. J.K.W. Ferguson, Connaught’s director since November 1955, and planning for his succession. The key question was, should the Labs’ position within the university be strengthened and renewed, or should a new arrangement be developed? Since 1917, Connaught had remained an unincorporated institution within the University of Toronto, under the trusteeship of the Connaught Committee.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

As Ferguson summarized to the Ontario Minister of University Affairs in August 1971, under this arrangement, Connaught had grown and evolved, with purposes and activities that were quite different from those of the university, with an administration that was for the most part separate from the university, and a separate employee’s union, and with policies also separate from the university with respect to personnel and inventions. However, Ferguson could only hope that the new Governing Council would be guided by the original terms and precedents set by Board of Governors. Ferguson suggested that a separate Board of Trustees could be appointed by the Ontario government from members of the Governing Council or elected by Alumni, or that a charter of incorporation for Connaught be granted, with all trustees appointed by the government. Ultimately, by late 1971, it was clear that some affiliation between Connaught and the University of Toronto would be maintained, with the best option being to restructure the Connaught Committee within the new Governing Council.[5] In a January 26, 1972, letter to the Chairman of the Board of Governors, J.E. Brent, Chairman of the Connaught Committee, proposed this new arrangement be part of the new University of Toronto Act.[6] However, within a week, the discussions about Connaught Labs’ future changed abruptly.

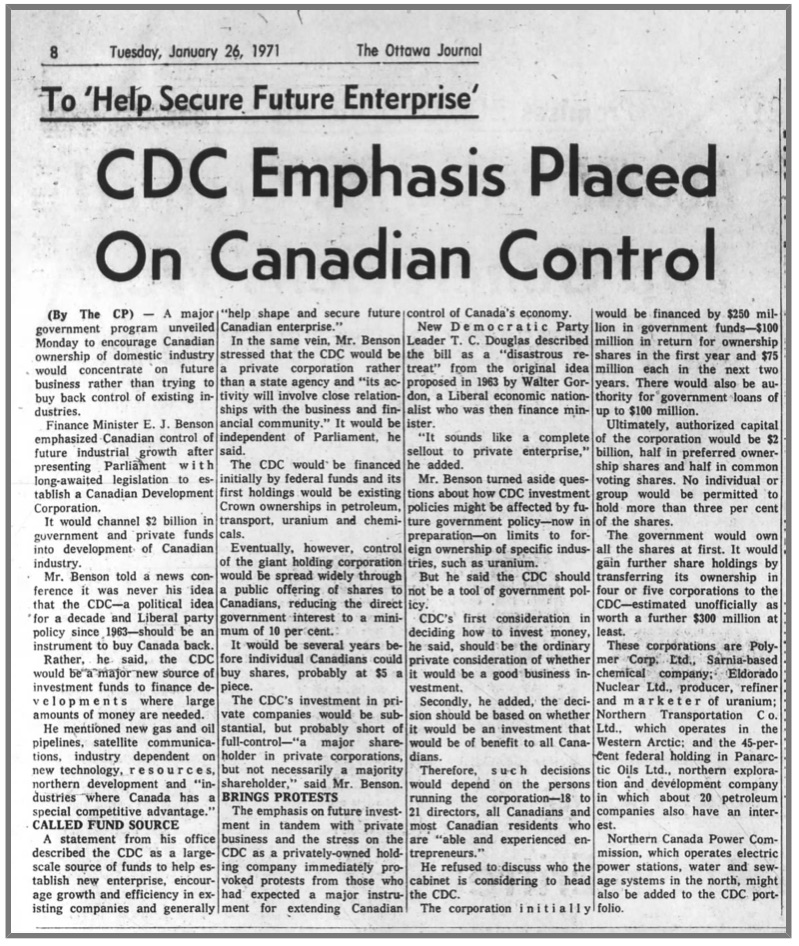

[Ottawa Journal, Jan. 26, 1971, p. 8]

At the end of January 1972, the University of Toronto received a compelling offer from the recently established “Canada Development Corporation” (CDC).[7] The CDC was established in 1971 as a federal crown corporation dedicated to developing Canadian business and industry across several sectors. It emerged out of public concerns about growing foreign ownership in the Canadian economy, especially in natural resources and industry. Such concerns prompted the Royal Commission on Canada’s Economic Prospects, followed by the “Watkins Report” in 1968, their findings leading to the creation of the CDC.[8] There had been previous offers to buy Connaught, but none had, as the University President’s Report for 1972 emphasized, “met with the kind of conditions the University wanted if it were to give consideration to losing a resource that had contributed so much in its own right and so much across the world to the reputation of the University of Toronto.”[9]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

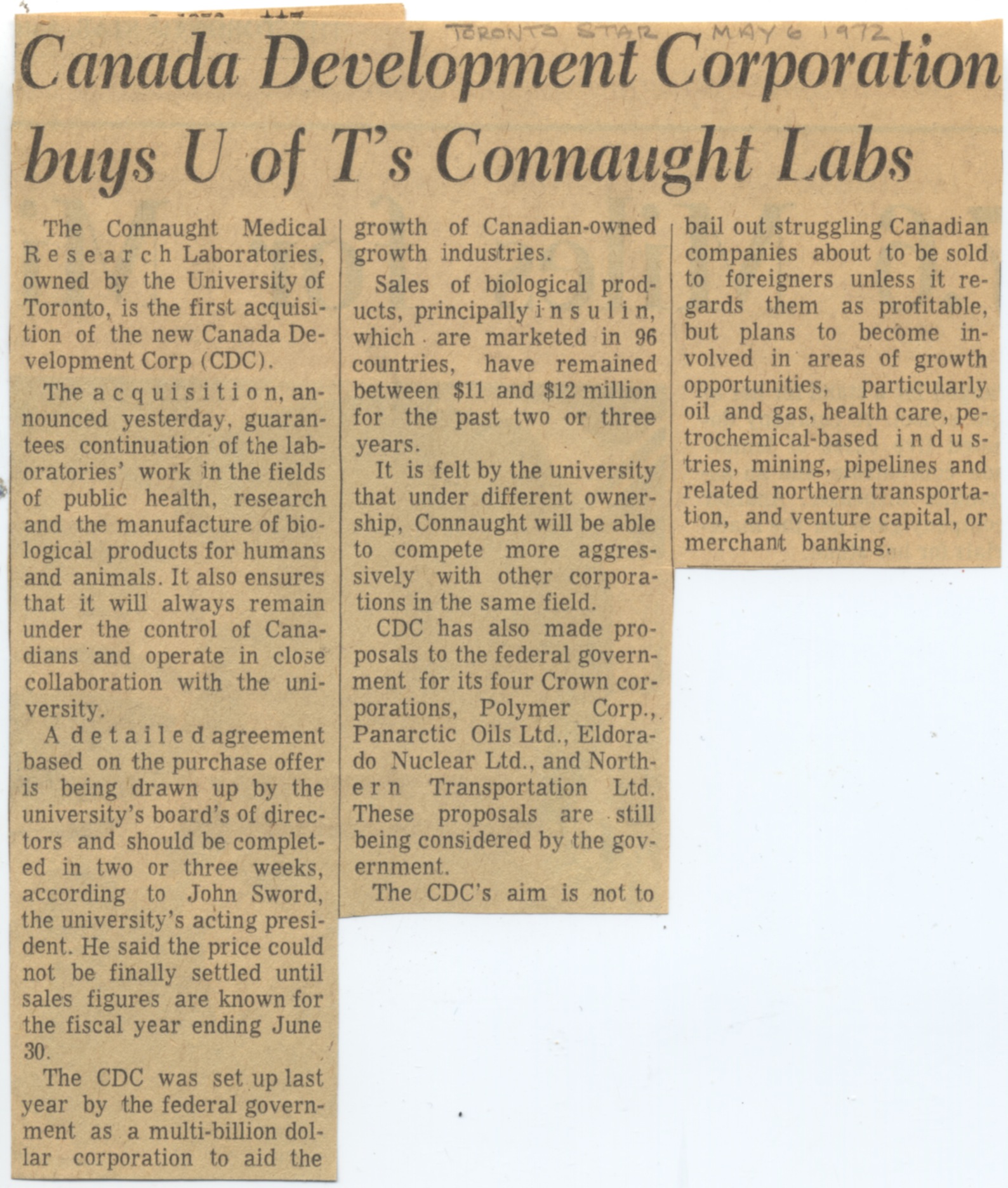

The CDC’s offer, however, did appear to meet such conditions. The price would not be determined until sales figures from the current fiscal year, ending on June 30, 1972, were known. Connaught’s annual sales over the previous 2-3 years had been consistent, between $11 and $12 million, while the other major factor in setting a price was the Labs’ capital assets. Beyond the price, the CDC’s offer guaranteed that Connaught would continue to play an important role in public health, scientific research would continue, the present full staff of about 800 would keep their jobs and an additional complement of some 200 scientists and researchers would be retained. It was also clear that the CDC did not plan to turn Connaught into a pharmaceutical manufacturing site that would produce “headache pills, for example.” The CDC was also committed to Canadian ownership, continuing production of essential vaccines and other biological health products, ensuring they were made available, especially to provincial governments, at the best possible price, and maintaining a close relationship with the university with respect to cross appointments and graduate student supervision. As the university’s acting president, John Sword, emphasized, “The CDC offer is the best solution for the future health and development of Connaught.”[10] However, on May 5, 1972, when official news broke of the offer and the university’s initial acceptance of it, the public and political reactions were mostly critical. The concerns focused mostly on the impact a profit-oriented Connaught would have on the price of its products, particularly insulin.

[The Toronto Star, May 6, 1972]

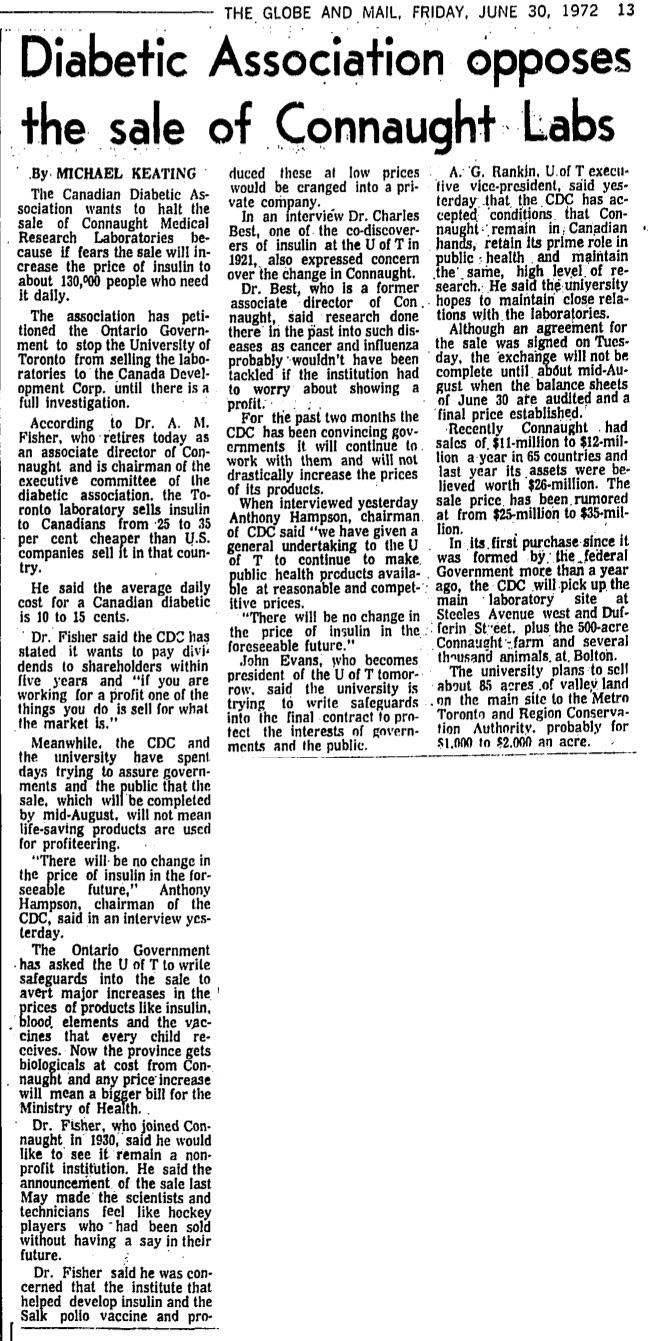

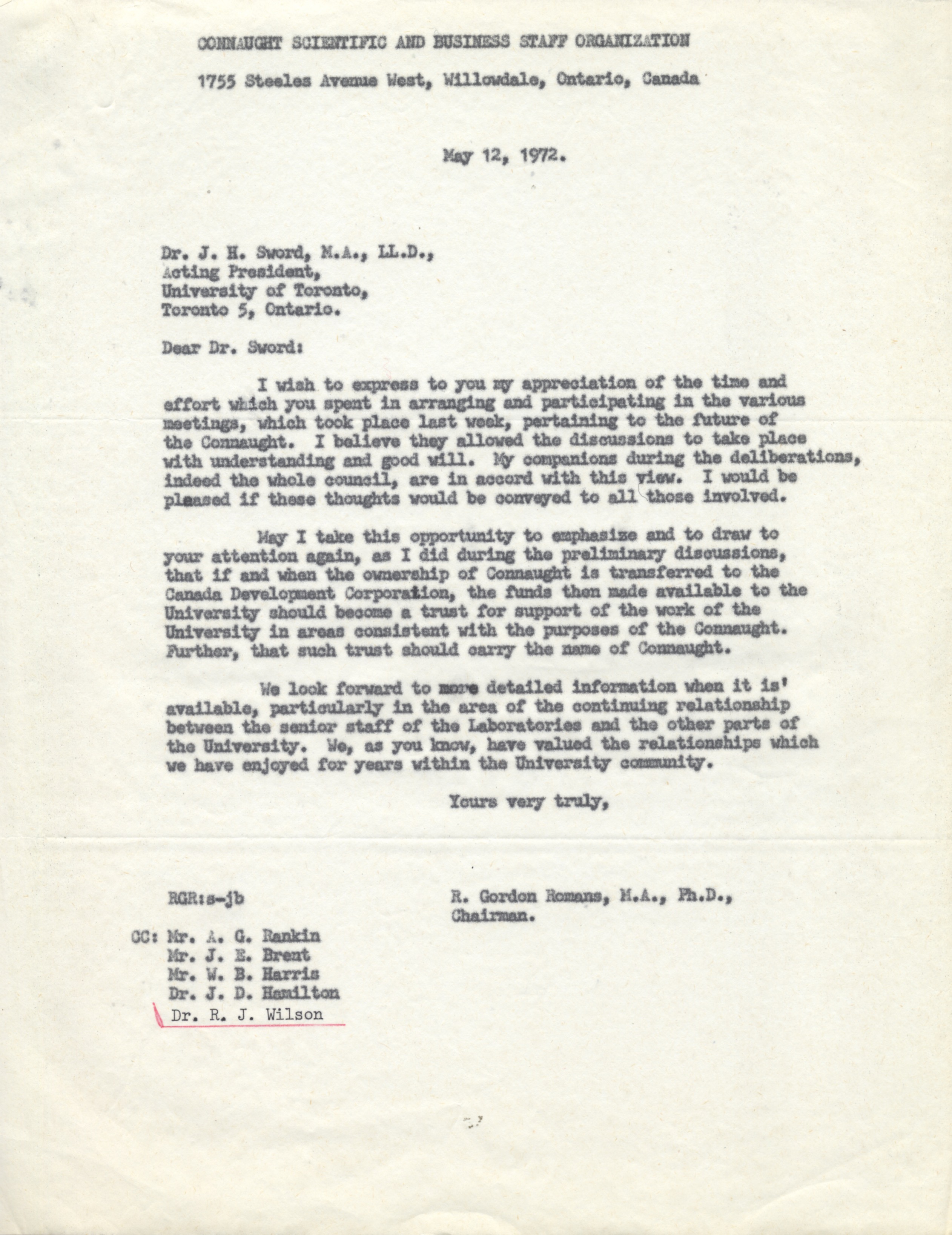

Among those most concerned about the proposed sale were the Labs’ senior staff members. Rumours about fundamental changes in the status of the Labs had circulated among employees, but senior officers were strictly limited in how they could discuss the situation. Indeed, as emphasized in a June 30, 1972 Globe & Mail article about the Labs’ pending sale, Connaught’s employees “feel like hockey players who had been sold without having a say in their future.”[11] Dr. R.G. Romans, President of the Connaught Scientific and Business Staff Organization, pressed for members of his organization to attend a meeting of the Connaught Committee to get permission “to discuss freely and frankly, with all appropriate members of the University, possible and desirable futures for Connaught.”[12] Ferguson further stressed to Sword that “senior members of our staff are responsible, loyal members of the University, whose work over the years has established the national importance of Connaught and its international reputation,” and felt strongly “that they can participate usefully in determining its future.”[13] At the May 2, 1972, meeting of the Connaught Committee, the delegation from the Staff Organization secured a meeting at Connaught for two days later with the Chairman of the CDC, who would explain the CDC’s intentions for Connaught. This meeting was soon followed by another, attended by Connaught’s full staff, which, as Dr. Robert J. Wilson, Associate Director of the Labs, underscored to Sword, “proved of great value in reassuring [the staff] about the future of Connaught and its continued relationship with the University of Toronto, of which we are all inordinately proud.”[14] While concerns remained about what the sale of Connaught to the CDC would ultimately mean, with Connaught’s leadership and staff agreeable to the new arrangement, the detailed legal and financial process between the University and the CDC proceeded.

[The Globe and Mail, June 30, 1972, p. 12.]

The price the CDC would pay for Connaught was based on an assessment of the Labs’ value as of June 30, 1972, which as was noted in the CDC’s Annual Report for 1972-73, amounted to “some $24 million,”[15] although $26 million was initially stated in press reports.[16] The sale of Connaught was formally completed on September 29, 1972, at which time it became known as “Connaught Laboratories Limited.” R.J. Wilson, appointed as Connaught’s Chairman of the Board, assured “all persons, organizations, agencies of government and others with whom we have always had excellent and very close relationships in the past will be more than pleased to know that our long standing traditions of service, quality, and research will be maintained unchanged, and that every effort will be made in future to widen our impact in the health care field consistent with this traditional image.”[17]

[The Varsity, Oct. 2, 1972, p. 10.]

Amidst the initial meetings among the CDC, the Connaught Committee and Connaught’s senior staff, a question of particular concern, especially among the latter, was what would the university do with the substantial sum of money the sale of Connaught would yield. In correspondence with Sword in May 1972, Wilson and Romans emphasized, as was suggested during the meetings, that the money should be put towards a separate trust fund to support research at the University that was “consistent with the purpose of the Connaught.” Furthermore, such a trust fund should carry the name of “Connaught.”[18] In particular, such a fund should support “scientific research, graduate fellowships in the health sciences or both.”[19] This plan also received the support of Ontario Premier Bill Davis, as well as the chair of the university’s Board of Governors.[20] The “Connaught Fund” was formally established in 1973 under the guidance of a re-established Connaught Committee. Its primary mission was “The promotion of research and development in medicine and other health sciences, and in other fields where the model of Connaught Medical Research Laboratories may be followed, namely the application of professional expertise and resources of the University to major problems of public interest.”[21] The Fund was designed to encourage a coordinated approach to the application of University resources and promote the interaction of various disciplines and groups within and outside the University. The Fund’s resources were to be primarily applied either in the initial stages of a major project or to secure outside grants to facilitate much larger projects than would be possible if the Connaught Fund was the sole source of support.

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

As Judith Chadwick, Program Director of the Connaught Fund, emphasized in the Fall 2014 edition of Edge magazine, published by the University’s Research and Innovation Office, the Fund “was intended to provide niche funding, and opportunity to bet on ourselves and launch research initiatives that might not otherwise be supported but that held great promise for addressing important questions and could eventually become sustainable through regular external funding.” She further underscored the unique nature of Fund in Canada, and that it was built on the legacy of a single innovation, especially the discovery of insulin and the essential role of Connaught Labs in developing and producing it, which “will go on to support University of Toronto research, potentially for as long as the University exists. That’s the exciting thing about Connaught — it is both old and new. It is history fuelling the future.”[22]

[Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives]

Since 1973, the Connaught Fund has evolved and grown, its Terms of Reference modified periodically, most recently in 1992, to permit the Fund and its granting programs to adapt to the changing structure and needs of the University. Funds were allocated by the Connaught Committee through the various granting programs based on the advice of four review panels, which represented the major research constituencies of the University. As of 2000, the Connaught Fund had invested $82 million into University of Toronto scholars, and as this is written, the Fund has awarded some $170 million since its establishment and is worth about $140 million. While the drifting apart of Connaught Laboratories from the University of Toronto left the university with the unique and increasingly valuable Connaught Fund legacy, after 1972 the Connaught Laboratories legacy continued to grow and evolve at Toronto’s northern border. As a commercial biologicals research, development and production operation under the ownership of the Canada Development Corporation, Connaught encountered some challenges, yet by 1978 was able to expand to the United States by acquiring a vaccine production facility in Switwater, PA. Over the next decade, Connaught’s North American successes led to its acquisition by France-based Institut Mérieux in 1989 and an identity change to “Pasteur Mérieux Connaught.” Despite two further global mergers — the creation of Aventis after the merger of PMC’s parent, Rhone Poulenc, with Hoechest of Germany in 1999, followed by the Aventis acquisition by Sanofi Synthelabo of France to create Sanofi-Aventis in 2004 — the original Connaught farm site thrives today as Sanofi Pasteur Canada, the largest biotechnology facility in Canada and home to over a century of Canadian scientific innovation.

Useful Resources:

Bator, Paul: Within Reach of Everyone: A History of the University of Toronto School of Hygiene and the Connaught Laboratories Limited, Volume 2, 1955-1975; With An Update to the 1990s (Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association, 1995) Sanofi Pasteur Canada, “The Legacy Project”: http://thelegacyproject.ca https://www.sanofi.ca/en/about-us/sanofi-pasteur

Endnotes:

[1] Connaught Medical Research Laboratories, Annual Report, 1965-66, p. 7. [2] Christopher J. Rutty, “Dr. Robert Davies Defries (1889-1975): Canada’s ‘Mr. Public Health’” in L.N. Magner (ed.), Doctors, Nurses and Practitioners (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1997), p. 62-69; article available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/Defries-biopaper.html [3] R.E. Binnerts to R.J. Wilson, “Competition in Biologicals for Human Use,” Jan. 14, 1972, Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives (hereafter SPCA), CLL General, 1971-93, Box 29; document available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/clients/docs/UTCF/Article-12/BinnertsRE-Memo-CompetitionBiologicalsHumanUse-1972-01-14-SPCA-CLLgeneral1971-73-Box29.pdf [4] J.C.W. Weber and W.R. Ashford, “New Drug Development Program: Connaught Medical Research Laboratories,” March 16, 1972, SPCA, CLL General, 1971-73, Box 29; document available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/clients/docs/UTCF/Article-12/Weber-Ashford-CMRL-NewDrugDevelopmentProgram-1972-03-16-SPCA-CLLgeneral1971-73-Box29.pdf [5] J.K.W. Ferguson to John White, Aug. 24, 1971, SPCA, CMRL Pre-sale Correspondence, 1971-72, Box 29; document available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/clients/docs/UTCF/Article-12/Ferguson-White-1971-08-24-SPCA-PreSaleCorr-1971-72-Box29.pdf [6] J.E. Brent to W.B. Harris, January 26, 1972, SPCA, CMRL Pre-Sale Correspondence, 1971-72, Box 29. [7] J.K.W. Ferguson to William B. Harris, Feb. 3, 1972, document available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/clients/docs/UTCF/Article-12/Ferguson-Harris-1972-02-03-SPCA-CMRL-PreSaleCorr-1971-72-Box29.pdf; and J.K.W. Ferguson to J.E. Brent, Feb. 14, 1972, document available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/clients/docs/UTCF/Article-12/Ferguson-Brent-1972-02-14-SPCA-CMRL-PreSaleCorr-1971-72-Box29.pdf; SPCA, CMRL Pre-sale Correspondence, 1971-72, Box 29. [8] https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canada-development-corporation [9] University of Toronto, President’s Report, For the Year Ended June 1972, p. 7-9; available at: https://archive.org/details/presidentsreport1972univ [10] “Connaught Laboratories to be first CDC purchase,” Globe and Mail, May 6, 1972, p. 1. [11] “Diabetic Association Opposes the Sale of Connaught Labs,” Globe and Mail, June 30, 1972, p. 13. [12] J.K.W. Ferguson to J.H. Sword, April 27, 1972, SPCA, CMRL Pre-sale Correspondence, 1971-72, Box 29. [13] Ibid. [14] R.J. Wilson to J.H. Sword, May 9, 1972, SPCA, CMRL Pre-sale Correspondence, 1971-72, Box 29. [15] “Report of Directors,” Canada Development Corporation, Annual Report, 1972, SPCA, Canada Development Corporation, Board of Directors, Box 29. [16] “The University completes sale of Connaught Labs to the CDC,” University of Toronto Bulletin, Oct. 3, 1972, p. 2 http://healthheritageresearch.com/clients/docs/UTCF/Article-12/UofTBulletin-1972-10-03-p2-CompleteConnaughtSaleCDC.jpg [17] R.J. Wilson to Harry M. Meyer, Oct. 6, 1972, SPCA, CDC 1971-72, Box 29; document available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/clients/docs/UTCF/Article-12/Wilson-Meyer-1972-10-06-SPCA-CDC-1971-72-Box29.JPG [18] R.G. Romans to J.H. Sword, May 12, 1972, SPCA, CMRL Pre-sale Correspondence, 1971-72, Box 29; document available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/clients/docs/UTCF/Article-12/1972-05-12-RomansRG-to-SwordJH-SPC-CMRL-PreSale1971-72-Box29.jpg [19] R.J. Wilson to J.H. Sword, May 9, 1972, Ibid; document available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/clients/docs/UTCF/Article-12/1972-05-09-WilsonRJ-to-SwordJH-SPC-CMRL-PreSale1971-72-Box29.jpg [20] Edge: Research and Innovation at the University of Toronto; The Connaught Issue, 16 (2) (Fall 2014), p 2; magazine available at: http://healthheritageresearch.com/clients/docs/UTCF/Article-12/Edge-Magazine-2014-fall-v16n2-ConnaughtIssue.pdf [21] “Terms of Reference” in “A Brief History of the Connaught Fund” (to 1990), and “The Connaught Fund” (to 2000), documents provided by Judith Chadwick, Program Director, Connaught Fund. [22] Edge: Research and Innovation at the University of Toronto; The Connaught Issue, 16 (2) (Fall 2014), p 2.